Winter in the forest is magical. We are often captivated by the snow blanketing branches, the morning light streaming through the canopy, and the crackling of ice and wood as wind blows into the treetops. But beneath our feet, a secret underground system is constantly at work. Plants are “communicating” with each other in remarkable ways - an essential process to sustaining the health of the ecosystem in every season.

Trees send and receive all kinds of information through a flexible, cooperative, and interdependent network. These messages come in the form of chemical signals that travel between nearby trees to prompt a variety of responses based on changing environmental conditions. For example, trees with extra water or nutrients are able to transfer this surplus to neighbors in need. Distressed trees can warn others in their network, even across species, about the presence of an incoming threat, like invasive bugs or the arrival of a drought. And a dying tree will endow any remaining carbon stores to its favorite neighbors in its final days.

Hidden networks

To fully understand the story behind the social system of trees, we must introduce another key player: fungi. Underneath the forest floor is a fascinating microscopic network of these spore-producing organisms, more closely related to animals than plants. Every step you take through a forest covers densely-packed fungal threads, which can span hundreds of miles if unfurled.

We’ve long understood there to be a symbiotic relationship between fungi and trees. Fungi consume a portion of the sugar that trees photosynthesize from sunlight; energized by these sugars, the fungi collect mineral nutrients from the soil, which are, in turn, absorbed by the trees. Yet recent scientific discoveries indicate that the fungi-tree interaction goes a step further. Fungi actually create the communication network that links trees together.

In healthy forests, mycelium, or the vegetative thread-like part of a fungus, fuse to the root tips of trees to build underground webs known as a mycorrhizal network. The trees, plants, fungi, and microbes in forests are so thoroughly connected that this network has become fondly known as the “wood-wide web.”

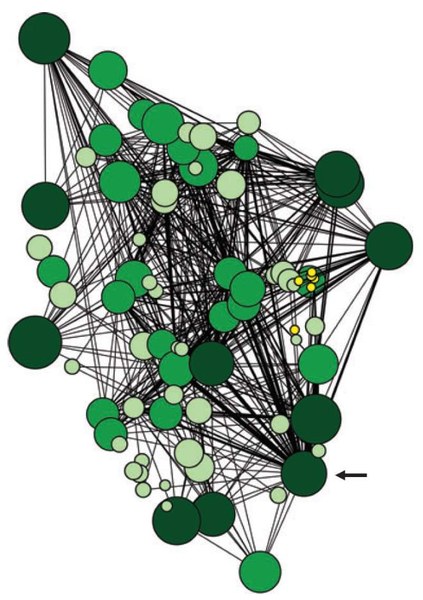

Model showing the linkages between Douglas firs through the mycorrhizal network by Beiler et al, 2010. The mother tree is connected to 47 other trees.

Model showing the linkages between Douglas firs through the mycorrhizal network by Beiler et al, 2010. The mother tree is connected to 47 other trees.

Mother trees

Deep in the forest, the hubs for arboreal communication are the “mother trees.” As the oldest and tallest, these trees tend to have bigger root systems and associate with more extensive mycorrhizal networks. To create a resilient forest, mother trees take on a supportive and nurturing role for trees in their network. Attuned to the needs of other trees and seedlings, these highly-connected trees detect nearby distress signals and adjust the flow of vital nutrients accordingly. For example, young trees do not yet have long enough root structures to independently retain sufficient water supply. Sensing this deficiency, mother trees soak up additional water from deep within the soil and facilitate its distribution to maintain the steady growth of the forest.

Throughout the winter season, mother trees are on high alert. With fewer hours of sunlight, many saplings struggle to receive enough light under the shaded canopy. Luckily, the height of mother trees means they have more access to available sunlight and can continue to convert this energy into sugar, sometimes generating more than they need for themselves. This extra sugar is redirected through the fungi-based mycorrhizal network to support saplings that are less likely to survive.

The story of a resilient forest is much more than what meets the eye. Next time you wander through the trees, take a moment to think about the world from their perspective. What conversations might be taking place under your boots?

This article originally appeared in our Winter 2022 issue of Mountaineer Magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, visit our magazine archive.

Issy Steckel

Issy Steckel