by Bam Mendiola, Mountaineers Intermediate Student

A cold silver padlock is pressed against my hand as my fingers stumble to regain dexterity. Clumsily, I align a set of small white numbers with a red and unforgiving arrow; the lock clicks open. I feel my face grow warm and my palms clammy. The cool touch of steel presses against my wet skin as I lean against a row of metal lockers. Nervously, I begin to undress.

Inside my bag I reach for a shirt that my mother gave me. An immigrant, she always prided herself in how well she dressed and groomed her children. As kids, we couldn’t afford the cereal brands the children on TV were eating (“Corn Flakes,” my mother called all cereal in her Spanish accent) but my siblings and I always had clean clothes and a good pair of shoes.

I grab the shirt and begin to dress my body in clothing that’s become both my weapon and my shield. Expeditiously, I slide into a blue shirt and cover the most vulnerable and resilient part of me: my heart. Suddenly, the cacophony of a screaming bell fills the air and I rush towards the green exit. I loved school but P.E. always made me nervous.

What if one of the guys thought I was checking them out?

Would they hate me if they knew I was gay?

From Classmates to Climbers

It has been over ten years since I stood in that high school locker room, but the memories are an old scar that reopen before every climb. I’ve since come out of the closet but the same questions continue to haunt me.

What if my tent-mate is homophobic?

What if he doesn’t want to sleep next to a gay guy?

It was the night of July 21, 2017. Darkness spilled into every corner of my room and filled the empty space inside me. I lay in bed looking up at the ceiling, feeling equal parts usurped and impostor. I wondered if I was good enough — if I belonged here (or anywhere really). The insecurity grew like the brick taking shape in my throat until my fear became a wrecking ball, destroying any chance of sleep. In the final hours of the night I became that nervous boy in the locker room again. This time, my old classmates became climbers and the row of lockers a field of crevasses. The bell that once saved me became a ticking time bomb disguised as a clock. Alexa, set my alarm for 2am,

I whispered to a glowing ring in the corner. Alarm set, the warm voice confirmed. In the morning I’d be attempting my first summit of Tahoma, better known by settlers as “Mt. Rainier.”

Hours later, I was driving my red Mini Cooper (Britney, I call her), filled with climbing gear and loud music. Mariah, Christina, and Rihanna each took turns lending their voice to my vulnerability and power as I drove to meet the mountain and my fellow climbers. Gathered in the parking lot and sorting gear, I was an unlikely and lonely climber in a sea of white — and I hadn’t even stepped onto the snow. Fists clenched with a chest full of cold air, I resolved to meet my fear on the mountain.

Before I climb, I count the ounces that I carry on my back judiciously. Prudent and discerning, I take only what I need and leave the rest behind. The heaviest load, however, is invisible. Homophobia, fatphobia, and racism take up space in my life — on my back — and weigh me down.

An Unfair Responsibility

Climbing all five stratovolcanoes in what is now known as “Washington” has not been easy. Pushing my queer, brown, more-than-10%-body-fat body to the summit of mountains has been an exhausting (and expensive) enterprise. Between course fees and $400 mountaineering boots — I purchased the cheapest ones I could find — my REI credit card reads like a who’s-who of a Patagguci party.

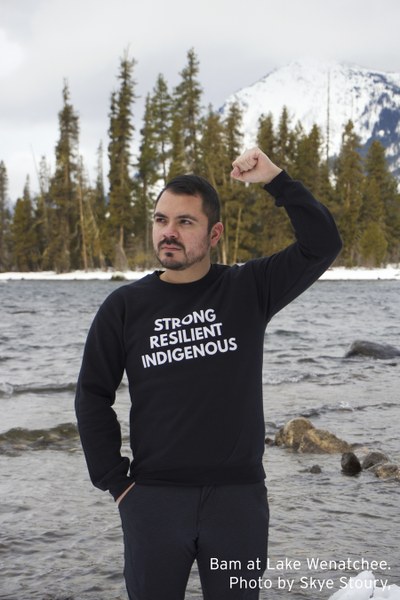

As I stretch my brown hands towards the sky to find a rock feature, I feel weighted. I carry the weight of realizing, more often than not, I’m probably the only brown or queer person for miles. When I traverse carefully on glaciers under the cover of darkness I’m keenly aware of the stereotypes society has perpetuated about me. I worry that my weaknesses will be attributed to my race, body size, or sexual orientation. When a heterosexual or white climber makes an error, nobody ever thinks it’s because they are heterosexual or white. When I make a mistake, I wonder if people will subconsciously believe its because Latinxs “aren’t educated,” round bodies are “lazy,” or queer people simply “aren’t outdoorsy.” I am a coalescence of intersecting identities, some of which also afford me unearned privilege. As a cisgender male in the backcountry, my gender is never questioned or associated with any personal shortcomings as a climber.

Being an unrepresented person in the outdoors also means you carry the unfair responsibility to represent every member of your community. Our voices are so rarely centered in the outdoor narrative that we feel responsible to speak on everyone’s behalf. White, heterosexual, cisgender men, for example, can afford to speak for themselves as individuals since their narratives are already widely and diversely represented. The only story I can share is my own but when I sign up for a climb I implicitly volunteer to represent all gay and Latinx climbers in the subconscious mind of a homogeneous group.

As a queer and Latinx climber, I also experience microaggressions. After a long and arduous hike, a fellow climber once exclaimed, “Bam, you’re a beast! I totally underestimated you.” At face value, this appears to be a compliment but I understand that the underlying assumption is that I wouldn’t be a strong member of the team. Of course, I wonder if it’s because I’m gay, not exclusively masculine presenting, and/or Latinx? Perhaps it’s because we’ve been taught to believe that only thin and muscular bodies can achieve tremendous feats. When I received this microaggression dressed as a compliment, all I could muster to say was, “Thank you.”

I began to share these experiences with members of the outdoor community and some people would ask, “If the mountains don’t care what you look like or who you are, why do you always bring it up?” It’s simple. It’s not the mountains I’ve been hurt by.

I’ve been hurt by people and our hegemonic systems of power. My skin is not a layer I can shed. When I move over snow and ice I cannot simply drop homophobia into a crevasse. As long as inequitable systems of power exist, I will continue to speak up. The microaggressions and tone-deaf responses have been deafening but I refuse to be complicit in the silencing of oppression. This is why diversity, equity, and inclusion matter to me. I’m not exotic. I’m exhausted.

Coming Out and Staying Out(side)

My parents, like their parents before them, were farm workers — caretakers of the land and bearers of fruit. My mother learned to hold the apple in her hand the way my grandfather held the guava. In my hand, I hold the fruit of their sacrifice and the privilege of choice.

Growing up as the child of Mexican immigrants, nature wasn’t a recreational playground. The great outdoors was a sunburn on my mother’s face, her skin the color of the Red Delicious. Nature was the callus on my father’s palms — his hands as rough as the frigid seas that threatened to swallow him alive as an Alaskan fisherman. Like my parents, I gave my youth to the land the summer I picked green beans from the earth. I spent my days filling crates with vegetables that middle-class children happily ate in commercials. I was paid by the pound. The great outdoors for my immigrant family has been the weight of the “American Dream.” For us, like many other working-class families, spending time outdoors meant long days, backbreaking nights, and unlivable wages. Growing up, the outdoors was not an idyllic wonderland. It was a means for survival. “Take a hike,” they said. They didn’t know the mountains we’ve already climbed.

The same summer I picked green beans in rural Idaho I also spent wishing I was someone else. I spent the majority of my teenage years faithfully trying to pray-away-the-gay. Eventually, I found the courage to live and speak my truth.

“Soy gay,” I said to my mother and father one summer night. My parents stood over me as my heart exploded into millions of nervous pieces that flew across the room like a shooting star in a dark sky. A scream escaped my mother’s lips and the horror that spilled from her mouth covered every part of me; it still does. If sounds were colors her wailing was crimson and my sobbing was blue. My father stood in the corner of the room in heavy silence; his face a shade of pale I’d never seen him wear before. I lay in a pool of sweat and tears and cried until sleep delivered me from the worst night of my life. My world as a I knew it fell out from underneath me and I wondered if I’d sooner drown from crying or die of a broken heart.

Building a Community

When I first began climbing, I searched social media for people I could relate to, climbers that looked and identified the way I do. I quickly found out that, as a queer person of color in the backcountry, I was largely alone. I decided to create visibility for my community so the next generation of climbers know that they belong.

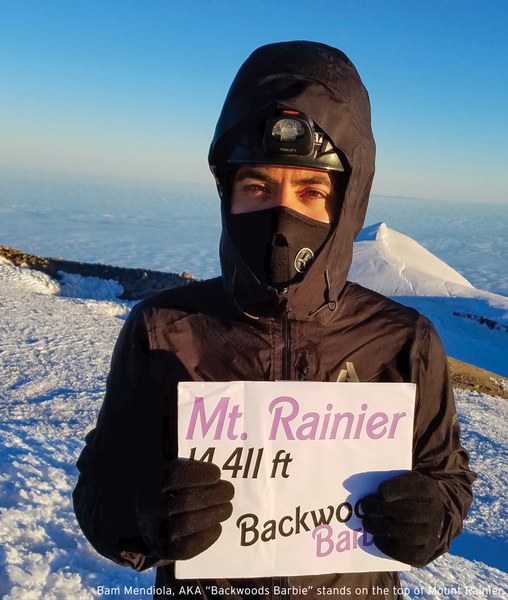

In 2015, after hiking countless miles, a friend affectionately nicknamed me “Backwoods Barbie.” It represents two of my identities — femininity and my love of the outdoors — that are often seen as antithetical when juxtaposed. As a climber, I fly my purple Backwoods Barbie flag from the summit of mountains and share my experiences on Instagram (@mynameisbam).

When members of your community occupy space, they leave a part of themselves for you to find. Today, those pieces are often digital. When you walk past them on the trail, or online, you see pieces of yourself reflected in their image. Everywhere we go we leave a lasting impression on the landscape. As ancestors, we can leave future generations a map of the places we’ve been and a legacy to help them get there. It is my turn now to be a good ancestor.

I continued to climb and search for brown faces and queer hikers that shared my story. I wanted to exchange a glance with someone on the trail whose smile said, “I see you.” Days can come and go in the mountains before I see another face that looks like mine. In The Unapologetically Brown Series, activist Johanna Toruño writes, “I woke up brown the way my mother and her mother made me/ the way the goddesses laid the earth on my skin as a shield/ my melanin a love letter from my ancestors / reminding me I am the heiress to the greatest gift I could receive/ the crown of the sun reigning on my skin.” As a boy who once dunked his face in milk to lighten the color of his brown skin, I was looking for someone to share my gift and pain.

The Summit Push

It was 11pm on July 23, 2017. My headlamp pierced the darkness as we began to climb under a new moon. Light from distant stars traveled thousands of years to meet my tired eyes at Camp Muir. Two climbers and I, connected by an umbilical cord made of rope, moved through the darkness and the universe. The silence of the night became our song; our inhale the crescendo — our exhale, decrescendo. Sounds of crashing rock and ice pierced the air and interrupted our aria with a sharp staccato. I took my final steps toward the summit of Tahoma that night and reflected on the trail I blazed to get here.

By sunrise, I stood 14,411 feet in the air on a monolith of earth and ice. The sun appeared in the distant horizon dressed in a blood orange glow. The summits of the metaphorical mountains I have climbed to get here took physical form against the surrounding horizon. If this catharsis were a color, it would be brilliant shades of orange and gold. For a moment in time, I felt connected to everything. I saw my face in the sun and my ancestors in the stars. I felt my body in the earth and my heart in the embrace of my team. It was then that I realized I wasn’t in nature; I am nature. When time started to move around me again I came undone and began to cry. I felt the howling winds carry away my tears before they had a chance to fall down my face. They were delivered back to the mountain in the shape of snow, leaving a piece of myself behind. That morning Tahoma lifted me and I released my insecurity like a red balloon on the highest peak of my beloved home.

Onward I go, with my backpack, my baggage, and my dreams. The highest mountains I have climbed are not made of rock or snow, but oppression and fear. Some climbs have taken me to summits. This journey has lead me back to me. The path I have blazed a reminder that I am enough.

I hope that when you see my face in the outdoors you discover a part of yourself — of nature — looking back.

Add a comment

Log in to add comments.Dear Bam,

This is a brave and beautifully created work, just like you.

Thank you for sharing your story.

Megan, thank you for reading it and for lifting me up. I appreciate you!

Wow Bam, this is powerful and gorgeously written. Thank you for sharing it!

Monica, I love the word "gorgeous" and I appreciate your choice of words here. Thank you so much for the shout-out and support!

I love this so much, Bam!!

Madeline, your comment made me smile. Thank you!

Bam, I met you hiking on the final class field trip in the Alpine Scrambling class a few years ago. I was the slowest hiker in our shortest-hike group. You took my picture at the summit.

Hiking with you was a ton of fun. It was inspiring too — you seemed so determined (and happy) to go on long hard hikes & backpacking trips, whether you had any hiking partners or not.

In the few years since, I hiked a lot more and got in much better shape. And went on some amazing (long, hard, totally worth it) backpacking trips. Partly because the way you talked about backpacking stayed with me. It helped me to get into good backpacking shape — and to get up and *go* backpacking. I wanted to be able to keep up, next time I hiked with you. Or next time I bumped into you on the trail.

I look scruffy and awkward in that picture you took, but it makes me happy when I see it anyway. The fabulous and badass Backwoods Barbie took that picture!

Thank you for hiking with me.

Hope to see you on the trail sometime.

Stephanie!

Reading this comment made my WEEK! I'm happy to report that thanks to the wonderful people I've met through the Mountaineers, I have more backpacking partners these days!

If you ever want to bump into me on the trail, let me know and we should go on a hike together! We could take a selfie and create more awesome memories!

<3

Dear Bam,

All I can is wow! Thanks for writing this and sharing it with us! Both inspiring and challenging us to do more to open our community!

Bam, this is powerful writing leading with so much heart. I disagree that we need to speak for anyone but ourselves. What's written here is an original constellation of experience that's rich and powerful and will inspire others to speak out loud their unique rich and powerful constellation. When everyone thinks they are speaking for everyone else, there is no more room left for us to share our unique complexities. Thank you for writing this.

Wow Bam! Thanks for telling this story. I hope I see you on a trip somewhere, with your flag proudly displayed in your arms. Incredible way to share your inner most feelings and thoughts. Thank you.

Bam Mendiola

Bam Mendiola