Cindy Ross is the author of nine books, including her first, A Woman’s Journey on the Appalachian Trail, which has been in print for nearly 40 years and has become a hiking classic. A former contributing editor for Backpacker Magazine, her column “Everyday Wisdom” was one of the publication’s most popular features. In April 2021, Mountaineers Books published her 9th book, Walking Toward Peace: Veterans Healing on America’s Trails, featuring stories of veterans who have struggled with PTSD and their journeys toward healing. This article includes excerpts from her most recent book in italics.

Walking on uneven ground while navigating the wild forces your mind to constantly assess and reassess your environment. You have to watch the ground, evaluate weather, and manage your body heat and nutrition. You need to be aware of your surroundings, scanning for anything out of the ordinary or unpredictable – anticipating surprises such as wild animal encounters, approaching storms, and so much more. You function in a super-charged state, even if it might not feel like it at the time.

This hyper-engagement exercises the brain in stark contrast to a life spent indoors focused on screens and electronic devices. The latter seems to breed disorders like depression and anxiety, whereas hiking feeds both the body and the brain. For people suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), the benefits of time outside are even more profound.

Post-traumatic stress disorder can result after a terrifying event. For civilians this most often happens after a natural disaster, a serious accident, a terrorist act, a rape, or other violent personal assault. Many veterans return from combat having experienced more than one of these types of terrifying events. Symptoms of PTSD may include flashbacks, nightmares, severe anxiety, and uncontrollable thoughts. These symptoms can interfere with your ability to work due to memory problems, lack of concentration, panic attacks, and emotional outbursts.

People with PTSD often have a difficult time assimilating into what many of us consider normal life. That’s because our brains run on electricity, with different wave patterns involved in different experiences and activities. Being in nature – whether walking in a park, paddling on a lake, or going on a longer hiking trip – helps shift the brain to a relaxed, focused electrical brainwave pattern. Studies show that spending time outdoors leads to a happier, more fulfilled life. These magical places significantly decrease your body’s concentration of cortisol and lower your pulse, blood pressure, and sympathetic nerve activity (the flight-or-fight response), all while increasing your parasympathetic nerve activity (the rest-and-digest response). Learning to switch into these relaxed patterns helps rewire the emotionally dysregulated PTSD brain into a calmer, more focused place – one capable of processing new learning and experiences. For some, the path to healing is a rather literal one.

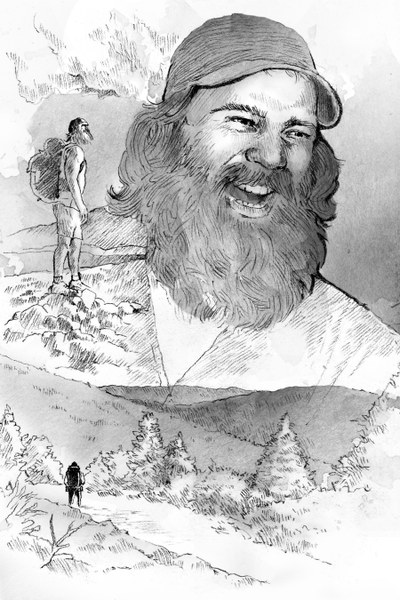

A portrait of Army Ranger Travis Johnston, illustrated by Cindy Ross's son, Bryce Glatfelter.

A portrait of Army Ranger Travis Johnston, illustrated by Cindy Ross's son, Bryce Glatfelter.

An unexpected path

My husband Todd and I both know how valuable long trails are, and what gifts can be had from walking their length. I have spent my whole life speaking, writing, and living long walks. Leading our small children and llamas across the entire 3,100-mile Continental Divide Trail, we witnessed firsthand how time spent in the wilds can influence and shape a life.

So while not completely out of left field, it came as a surprise to our family and friends when Todd and I created River House PA, our nonprofit designed to help veterans heal in nature. It seemed an unlikely marriage: an organization for combat vets paired with two freedom-loving, adventure-seeking, Triple Crown-hiking pacifists. Yet it made sense to us, and for seven years we’ve been privileged to join veterans as they fight to heal their minds and bodies.

It started back in 2013, when a group of veterans started down the Appalachian Trail (AT) on Springer Mountain, Georgia, with their eyes set on reaching Mount Katahdin in Maine over the course of six months and 2,100 miles. Prior to their trip, I was contracted to write a magazine story about the group of four. Following their progress on Facebook, I watched as they slowly made their way north, navigating the joys and perils of long-distance hiking. Their path was filled with lush forests, river crossings, cold nights, and swimming through multiple feet of snow in Georgia. As the days went on, I watched the trail slowly carve them into lean, strong legged-hikers. I found myself more and more invested in their journey.

Although I was not a member of their elite club – I had never served our country nor experienced war – we did share membership in another specialized group: the long-distance hiker. We were comrades in that sense, and at our home in Pennsylvania a little beyond the halfway point, the four vets came as guests to our hand-built log home in the woods.

A connection

I was planning to host the vets for one night, figuring they’d walk right back out of my life. But on the first morning they decided to day hike north without their fully weighted backpacks (known to thru hikers as slack-packing). At the end of the day I picked them and drove them home for another night of good rest and big meals. One day of slack-packing quickly turn into two, then three, then four. The time in nature and rest and relaxation at our home was clearly doing them good. They jumped out of a tree into the refreshing river and swam at my friend’s pool. We laughed around the picnic table every night over supper, and they took turns doing dishes. They started to feel like regular family members.

When they began to trust us, they began to talk.

They shared their deeply moving stories of war and their suffering. It wasn’t enough to pack thirty pounds on sore knees and aching muscles; they also hauled war-induced nightmares and memories up the mountains. The trek spurred recollections of years in the service: images of dead comrades, the torment of second-guessing orders, questioning their own survival while others had perished. These thoughts haunted the veterans as they climbed. Mile after mile, though, they began to leave such thoughts behind, to deposit memories on the valley floors and ascend to greater heights of acceptance of their lives and their service. Through hiking, these vets came to terms with much of what they saw, experienced, or may have had to do, just as they accepted nature’s harsh terms of steep climbs, rocks and roots, and stormy weather. Their dark pasts began to recede, much as the mountains they summited faded into the distance. They weren’t walking away from their histories; they were learning to live with them and themselves. You cannot get rid of the past, but you can learn to live with it, grow from it, and work to be free from its emotional turmoil.

As they traveled the Appalachian Trail, these veterans experienced a roller coaster of emotions. They shed tears of joy at the beauty of the world and the fate that allowed them to return home while their best friends perished. There were also tears of regret over death and the horror inflicted on fellow human beings. These emotions - survivor guilt, grief, moral injury, shame over killing fellow humans, fury and desolation that others had killed their best friends - fueled their PTSD. As the miles passed, they were able to move, oh so gradually, toward acceptance and forgiveness as they walked toward peace with each step.

Before these intimate conversations, Todd and I were clueless. We have no family members in the military. No contact with war. When these four vets opened their hearts to us, Todd and I learned of the heart-wrenching struggle of the returning veteran from war, and we wanted to do something more to help.

Since 2001, more than 2.7 million veterans have been to the war zones in Iraq and Afghanistan. According to a March 2019 annual report on national suicide prevention by the US Department of Veteran Affairs, one in five veterans have been diagnosed with PTSD. Many veterans who suffer with PTSD never seek help and have never been diagnosed. An average of seventeen veterans (the number is twenty if you include active duty and National Guard) die by suicide every day, totaling almost sixty thousand veterans since 2010. That is more than the total number of lives lost in more than eighteen years of combat in the Middle East. This is a tragedy and a failure as a nation.

These staggering numbers have forced therapists, caregivers, and researchers to think outside the box to find alternatives to traditional therapies and prescribed medications for veterans with PTSD, depression, and anxiety. One of the most innovative approaches is ecotherapy, which uses outdoor activities in nature to improve mental and physical well-being. Hundreds of studies have been conducted in the past decade or so convincing even the most skeptical that spending time in nature has healing power. Since walking is so accessible, the activity of hiking is one of the easiest ways to reap the benefits of nature’s healing.

One veteran, Travis Johnston, whom I became very close with, exhibited one of the most profound changes I’ve witnessed after prolonged time on the trail. Travis was a Special Forces Army Ranger, serving on the most intense missions and experiencing intense trauma. Consequently, the more war trauma, the longer the path to healing. Upon reaching the AT’s northern terminus on Mount Katahdin in Maine, he shared this:

“Hiking from Georgia to Maine gave me a new mission and my trail family became my new brotherhood. I learned that being completely isolated is not good for me. I need a family who is experiencing the same hardships and joys as I am, just like in the military. I also learned that I had to be patient and accept this new experience, replace those bad memories with new good ones. War is not normal but being in the woods and hiking the trail felt normal, it felt good, and it wasn’t a masking agent like drugs or alcohol. Looking back now, I had been so close to dying many times. When I descended off Mount Katahdin in Maine, I didn’t feel like I had just finished the AT; I felt like I was starting the rest of my life. Anything moving forward was possible.”

Travis went on to complete the entire Pacific Crest Trail and the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail, earning the coveted Triple Crown of Hiking.

“The trails were a kind of beautiful bridge in my life. They helped me see things more clearly, for hiking strips away everything that doesn’t matter. The trails helped me grow and set me up for the long term. Before, I could not believe that I even had a future. I simply could not envision one. I never thought that I would live this long, or even want to. Who I am today is very far from that Ranger who just arrived home from deployment.”

A group of veterans take a day hike on the Appalachian Trail.

A group of veterans take a day hike on the Appalachian Trail.

Finding peace

While a short hike in nature is beneficial, a long walk can reap even more benefits. Sometimes, more than one long hike is needed for the most tormented of souls. The Appalachian Trail can be the first five million steps to healing.

My experience with these long-distance hiking veterans inspired me to form River House PA so I could help those individuals who had already given so much of themselves. The nature-based outings we conduct are mostly hiking and paddling, but we’ve also been known to throw an inner tube down the river, take a bike ride on a rail trail, and even host a yoga class. In the depths of winter, we go on owl walks with local birding naturalists, attempting to call in the elusive birds. We make campfires, serve home-cooked meals, and provide a safe space for vets to experience camaraderie in the peace of the outdoors.

We often work in tandem with recreational therapists at nearby Veterans Administration health facilities. Local veteran hospitals and medical centers bring vans filled with veterans enrolled in rehab programs for PTSD, substance abuse, homelessness, or all of the above. They are accompanied by their recreational therapists, many of whom have become close friends as we work together to help the vets create a satisfying life where they can make healthy and positive choices. The easy part is experiencing how time spent in nature can make you feel so good.

Wayne Storm hiking an impressive 4 miles on crutches.

Wayne Storm hiking an impressive 4 miles on crutches.

Gratitude poured from the veterans’ hearts - gratitude for being alive (some have attempted suicide), gratitude for coming to a place of light after so much darkness, gratitude for a second chance, gratitude for the woods and nature and the hike, and gratitude to the rec therapists for believing in nature-based therapy. Some veterans had never been in a forest before nor on a hike. They spoke of their renewed desire to climb out of the dark hole, to make wiser, more healthy choices. Tears silently trickled down some of the veterans’ cheeks.

At our events, we don’t ask our veterans about their war memories unless they want to talk and share. We provide a welcoming place for them so that they can talk amongst themselves. When the vets come to our log home and forested property, we show them our large organic orchard and garden. We have them crank homemade ice cream. They sit around the campfire and admire the stars. All of this has the potential to culminate into tremendous peace, and for many it has.

Through the veterans’ collective stories of wartime traumas and their present lives, what has become clear to me is that anyone suffering from any form of PTSD may discover the powerful comfort and healing that can be found in the outdoors. You just have to take the first step.

Tommy Gathman, “The Real Hiking Viking,” illustrated by Bryce Glatfelter.

Tommy Gathman, “The Real Hiking Viking,” illustrated by Bryce Glatfelter.

Walking Toward Peace: Veterans Healing on America’s Trails is available for purchase at our Seattle Program Center bookstore, online at mountaineersbooks.org, and everywhere books are sold.

This article originally appeared in our Summer 2021 issue of Mountaineer Magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, visit our magazine archive.

Cindy Ross

Cindy Ross