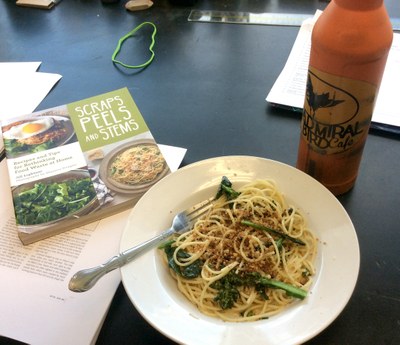

A book I worked on for the Fall 2018 season, Jill Lightner’s Scraps, Peels, and Stems, will have a lasting impact on me. The recipe for Spaghetti with Crumbs (we call it “that crumby spaghetti” at my house) is so simple—and I’ve made it so frequently—that I pretty much have it memorized by now, but I definitely turned to Jill’s book (page 111) to see how to tell a truly fresh egg from a slightly more vintage one:

Whole, fresh eggs come stamped with a best-by or sell-by date; stored in the refrigerator, they will last for at least four weeks past that date. If your fresh eggs are well past the very last reasonable date you think they might be good, there’s one test to try before cracking them open. Put a few cups of cold water in a small bowl and submerge the eggs one at a time. If they stay on their sides on the bottom, they’re fine; if they stay submerged but the tops point vertically, it’s time to hard-boil or eat immediately; if they float, toss ’em.

(True confession: for most of my life I didn’t know eggs could go bad. Which maybe explains why I never liked eggs cooked at home.)

The spaghetti with crumbs truly is simple and delicious—and it encapsulates some of the reasons I like this book so much:

I almost always have the ingredients I need for it on hand. It uses simple dried pasta. I’ve made it with spaghetti, and with penne, and with bowties. I think I’ve even made it with a combination of whatever dry pasta I had sitting in the cupboard (because you never use the entire box of penne/bowties/shells/fusilli/you-name-it, just three-quarters of it).

I almost always have the ingredients I need for it on hand. It uses simple dried pasta. I’ve made it with spaghetti, and with penne, and with bowties. I think I’ve even made it with a combination of whatever dry pasta I had sitting in the cupboard (because you never use the entire box of penne/bowties/shells/fusilli/you-name-it, just three-quarters of it).

The other main ingredient is essentially any sort of green you might have wilting in your refrigerator and there’s almost always something in there that I thought I’d use but haven’t. My favorite green is one Jill doesn’t list: Broccolini.

And the crumbs! For years, I have remorsefully thrown out portions of baguette purchased on Sunday that have gone stale by Wednesday. But thanks to Scraps, Peels, and Stems I am treasuring those ends of baguette, letting them go even staler, whirring them in the blender, and then putting them into a ziplock bag in the freezer to pull out triumphantly when we “have nothing in the house for dinner.” Browned in a bit of olive oil and garlic, they fill the house with a delicious aroma and make plain pasta and greens something exotic. (Jill also offers some other ways to use stale bread, including a savory variant on French Toast that I’m planning to try this weekend.)

The book contains recipes—dozens of them—that show me how I can turn what I have in the kitchen into a snack or meal instead of ordering pizza yet again, but it’s more than just the recipes. Scraps, Peels, and Stems has me seeing how I can think differently—better—about preventing food waste. Less guilt. More action. For example:

I’m now aware that some foods (like apples) will cause others (like avocadoes) to ripen more quickly so I should keep those items in different parts of the refrigerator. When it came time to make apricot preserves this year, I talked to the vendor at the farmers market about buying a smaller quantity than the full box we usually get because I knew I really couldn’t use that many. (It turned out he was happy to sell me a lesser quantity since he didn’t want the literal fruits of his labor wasted either.) Rather than throwing out bacon and chicken fat, I’ve been pouring it into a jar I keep in the freezer and using a scoop of it when I want an extra kick in a sauce or fried potatoes. That little freezer, in fact, is getting a lot more work than it used to do; it also contains a bag of rolled-up strips of bacon so I’m not faced with the “I’d like two strips of bacon but I don’t want to buy a whole pack” dilemma. And when I had such a bumper crop of Concord grapes that I couldn’t use all of them in making jam and pie filling, I thought to call City Fruit to collect a box from my porch instead of just adding the extra fruit to the yard waste container.

I am unlikely to follow Jill’s example in everything—I just don’t want to weigh my food waste every day and I already don’t eat meat very often—but I am far more mindful of how many bags of kitchen waste I’m carrying out to the bin (spoiler: it’s fewer these days) and I’m a lot more determined that not one scrap of animal product is going to be thrown out (surprise discovery: it’s stinky cheese that is the most challenging).

Thanks to Jill’s book, I don’t automatically go out and buy the exact ingredients called for in a recipe (either in this book or elsewhere): I stop to ask myself if I really need that ingredient I don’t have or if there isn’t something else that I do have that could be substituted instead. There are plenty of action steps I’ve not yet mastered, but I will. Just as Madi Carlson’s Urban Cycling made me a year-round cyclist, Jill Lightner has me rethinking food waste at home” on a daily basis.

Mary Metz

Mary Metz