Sometimes when we take a close look at a particular page in history, we find that the most commonly believed story is not necessarily the most accurate. Omitted facts, hidden characters, and forgotten conversations linger in an archival twilight zone, waiting to be unearthed to reshape the past. Their discovery can be thrilling.

The stories we tell as we explore the outdoors are no different. As we move through the mountains and across the waters of the West, the origins of some of our most beloved parks and trails pique our interest and make us wonder – how did this come to be, really? Several years ago, I realized that the origin of the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) might be a page in our history books that needed dusting.

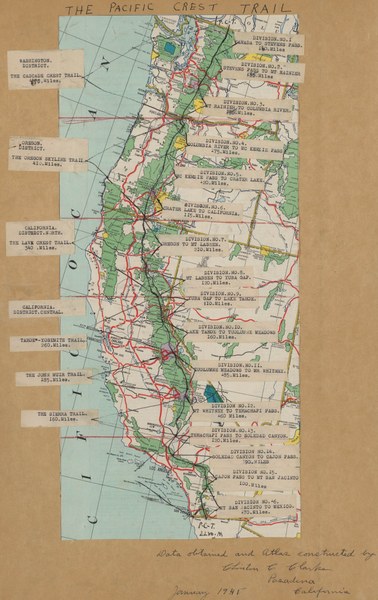

Early Clarke map of the Pacific Crest Trail. Courtesy of Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

Early Clarke map of the Pacific Crest Trail. Courtesy of Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

The story we knew

“The Pacific Crest Trail originated in the 1930s from the mind of Clinton C. Clarke,” stated the Pacific Crest Trail Guidebook in 1973. The June 1971 issue of National Geographic pronounced Clarke “the father of the Pacific Crest Trail.” But was the Pacific Crest Trail actually conceived by Clarke? Tall and robust, with slicked-down hair and a penchant for bow ties and tuxedo-collared shirts, Clinton C. Clarke was the picture of wealth in the early 20th century. Born into money, he once called himself an “investor.” He didn’t work for a living, but he knew how to work a good cause. He founded the Pasadena Playhouse and was a prominent early Boy Scout Leader. When Clarke married in 1906, he and his bride took a ten-month, 20,700-mile around-the-world cruise.

Clinton C. Clarke passport photo. Courtesy of Don Rogers.

Clinton C. Clarke passport photo. Courtesy of Don Rogers.

Still married and well into his fifties, Clarke began working a new cause – a hiking trail from Mexico to Canada to showcase the glory of the western US. He began promoting the concept of the PCT in early 1932, sending torrents of letters from his home, a well-to-do hotel in Pasadena, California. Bent over in his comfortable armchair, Clarke pieced together over 2,000 miles of existing trails, dirt roads, and segments that were, at best, wishes. He was living in the time of the Great Depression, and unemployment was peaking at a staggering 24.9 percent. Though there was government encouragement, there was no government aid to promote the PCT; Clarke self-financed over 12,000 copies of pamphlets, books and trail maps.

He wrote the head of the National Park Service, Horace Albright, an early PCT backer: I’ve completed a 65-foot-long map set of the entire proposed trail. Clarke’s two PCT books contained packing lists, knapsacking advice (“put a raisin under your tongue”), and onion-skin maps of the proposed trail. In each book Clarke recounted: In 1932 I wrote to the heads of the Forest Service and National Park Service proposing a trail from Mexico to Canada, running along the mountain crests of California, Oregon, and Washington, and those august gentlemen wrote back appointing me in charge.

Shrinking violets don’t advance great ideas. Author Dan White described Clarke in his book Cactus Eaters as: “One part John Muir, five parts George Patton.”

In 1935, Clarke convinced the Sierra Club to sponsor the first Pacific Crest Trails System conference. Ansel Adams sent out the invitations. At the conference in Yosemite Valley, the YMCA adopted an audacious plan for a PCT Relay. Forty teams of Depression-era boys would each hike a 50-mile segment of the trail, passing off a gold-leaf-embossed leather logbook from one team to the next. The relay took four summers to complete, spanning from 1935-38, sometimes pushing north on sheer faith. Thirty-one YMCAs participated. When the last team finished and crossed back into the U.S. from Canada, they were met by Governor Clarence Martin in Blaine, Washington. The relay generated a cascade of publicity, dozens of newspaper articles, and a nationwide, two-page splash in the popular Sunset magazine.

Like a well-launched rocket, the PCT had begun a trajectory that would carry it far. In 1968 President Johnson signed the National Trails System Act, designating the PCT as one of the first “National Scenic Trails.” From the 1970s onward, successive waves of backpackers heightened interest in the trail. The 21st century brought a bestselling book and an Oscar-nominated movie. To get a permit to hike the trail in its entirety today, you compete with over 10,000 other eager hikers in an annual lottery.

The other Hazard

Far afield from glamorous Pasadena sits Camp Muir, perched among the heavy glaciers of Mount Rainier, a well-used staging point to reach the summit. But less-used Camp Hazard sits at 11,188 feet, just below the Kautz Ice Fall. Few today know the source of its name, though many assume it’s called “Hazard” because the camp is dangerous. Some believe it’s named after Hazard Stephens, the first to summit Mount Rainier. In truth, Camp Hazard is named for a Mountaineers member once so well-known that, when he drove to Bellingham on January 13, 1926, to give a talk at the city’s Mount Baker Club, his arrival made front page headlines. “Hazard Toots his Horn: Fog Forces Mountaineer to Creep into City.”

Joseph Hazard was a big barrel-chested man who was fond of announcing, “I weigh one-tenth of a long ton.” His proclamation turned out to be accurate. The Bellingham Herald called Hazard a “celebrated” climber, “accustomed to finding his way up the most hazardous slopes.” The article also included his weight: 225 pounds.

Whether his size, personality, or talent as a climber were the cause, Mount Rainier National Park Place Names states: “Camp Hazard… was named for Joseph Hazard by The Mountaineers in 1924.” Hazard wrote five books, and in one he set the record straight. Camp Hazard, he wrote, was named “to honor both [my wife] Margaret and me.”

Margaret Hazard may not have weighed 225 pounds, but she was imposing in her own right. Margaret served as the editor of The Mountaineers Bulletin and The Mountaineers Annual, served on The Mountaineers Board for more than a decade during the 1920s and 1930s, and was a well-regarded climber.

That day in 1926, Joseph Hazard traveled to Bellingham alone. He was set to regale the Mount Baker Club with tales of his and Margaret’s recent ascent of Mt. Fuji. But prior to his evening engagement, the famed climber had one other task to attend to.

Miss Montgomery

The era of the early 1900s was one where newspapers often identified a woman by their husband's name: “Mrs. David Brown” or “Mrs. Robert Curtis.” Well into her fifties, “Miss Catherine Montgomery” was a founding faculty member of a teacher training school in Bellingham – a school today we know as Western Washington University. When she wasn’t guiding future elementary school teachers, Montgomery could be found tramping, her one true love.

Catherine Montgomery circa 1910. Courtesy of Washington State Parks

Catherine Montgomery circa 1910. Courtesy of Washington State Parks

The word hiking wasn’t yet in vogue, and the word backpacking wouldn’t come into use until a decade later. But Montgomery, a “tall tree” as one student described her, was a fearless outdoorswoman. We’d call what she did hiking and backpacking, and we’d be aghast that the day’s morals required her to wear full-length bloomers and a high-neck shirt into the wilderness.

In 1926, Montgomery was the “Supervising Teacher of Primary Grades” and one of her roles was to review and purchase textbooks. That Wednesday morning she had a one-hour appointment with a textbook salesman from Benj. H. Sanborn & Co. – none other than Joseph Hazard. He might have been a famed climber, but his day job was selling Sanborn textbooks.

The meeting took place in a basement office of the college’s original building, Old Main. Hazard had to duck his head to get into the room. Near where she sat, Montgomery had a two[1]year-old issue of American Forestry magazine. The issue had one of the first articles about the Appalachian Trail.

A tramper’s suggestion

In Montgomery’s office, the fearless climber gave an anxious presentation. Two decades later, he recounted what she said to him at the meeting’s end:

“Do you know what I have been thinking about, Mr. Hazard, for the last twenty minutes?”

“I had hoped you were considering the merits of my presentation of certain English texts for adoption!”

“Oh that! Before your call I had considered them the best—I still do! But why do not you Mountaineers do something big for Western America?”

“Just what did you have in mind, Miss Montgomery?”

“A high winding trail down the heights of our western mountains with mile markers and shelter huts—like these pictures I’ll show you of the ‘Long Trail of the Appalachians’—from the Canadian border to the Mexican Boundary Line!”

The conversation was recounted twenty years later in 1946, in a book written by Hazard that had a small print run. The publisher of the PCT Guidebooks came into possession of one of the few available copies and included Hazard’s story in their 1977 second edition. But for this serendipitous event, none of us would know about Montgomery’s role in the origins of the PCT.

JOSEPH HAZARD (FAR LEFT) IN 1925, OFF TO CLIMB MT. BAKER. COURTESY OF WHATCOM MUSEUM, WASHINGTON.

JOSEPH HAZARD (FAR LEFT) IN 1925, OFF TO CLIMB MT. BAKER. COURTESY OF WHATCOM MUSEUM, WASHINGTON.

Hazard’s book added that he carried Montgomery’s idea to the Mount Baker Club the night of his 1926 presentation. Hazard reported that the idea spread amongst fellow climbers and to other local outdoor clubs from there.

Digging through history

This story was the extent of our knowledge about Montgomery’s involvement in 2008 when I set out to discover if she was truly the origin point for the concept of the PCT. Surely, some record must exist. I sought out 1920s records from northwest outdoor organizations. The Mount Baker Club proved a dry well. Though founded in 1911, all of its pre-1928 records had been lost, and no club records corroborated Hazard’s long-after-the-fact story. The Mazamas, a climbing club in Portland (and The Mountaineers sister organization), had extensive records dating back to its founding in 1894. But even working with their archivists, we found no hint of Montgomery’s and Hazard’s 1926 PCT conversation. The same held true for the Trails Club of Oregon.

In 2009, I found myself deep in The Mountaineers archives at their Seattle Program Center. I’d been given access to a locked glass case with the club’s original board minutes books. Starting in 1926, I immediately perked up when I saw Margaret Hazard was a board member. The minutes showed that Joseph Hazard attended a board meeting late in 1926. “This has to be it,” I thought. But there was no mention. I read on through the minutes for 1927, and then into 1928. It was getting late, nearing 8pm. Discouraged, I kept turning pages. It felt like hiking well past dark. I was ready to turn in. Just a few pages more…

Sept. 6, 1928: “Motion passed that the Trails Committee be revived and that the matter of a trail all up and down the Pacific Coast be referred to the Trails Committee.”

Oct. 4, 1928: “The President reported [about] the committee…for the trail from the Canadian Border to the Mexican Border.”

Pay dirt! A contemporary record did exist, pointing to the Hazard and Montgomery conversation. The minutes confirmed Hazard’s claim that the idea had been passed from the Mount Baker Club to others. Not only that, but The Mountaineers minutes also noted multiple trips by its members to trail events in Los Angeles. Pasadena was close by. They were in Clinton C. Clarke’s backyard.

A chapter closes

A few months after meeting with Hazard, Montgomery ended her 40-year teaching career. It’s unlikely the two ever met again. Montgomery remained in Bellingham until 1957 when she passed away at age 89. That same year in Pasadena, Clinton C. Clarke died.

For the Pacific Crest Trail, World War II and its aftermath was a quiet time with little public interest. Montgomery’s 1957 obituary lauded her teaching career, but made no mention of the PCT. Sadly, she probably never knew that she’d given birth to the trail.

On September 27, 2009, not long after my visit to The Mountaineers archives, I submitted a nomination form. One year later, I stood in a large hall in Bellingham and saw Montgomery inducted into the Northwest Women’s Hall of Fame. Speakers lauded Montgomery’s life – a teacher, ardent suffragette, founder of a major college, and founder of two still-existing women’s clubs.

Here is the last paragraph of her induction citation:

“Of her many legacies, perhaps the most enduring is her vision of a hiking trail along the ridges of the Pacific Coast that she began to champion starting in 1926. Others took up the cause and, today, that 2,650 mile-long trail that runs from Canada to Mexico attracts thousands of hikers. She is justly called “The mother of the Pacific Crest Trail.”

Though she never had the chance to set foot on the 2,650- mile trail, Catherine Montgomery’s idea ignited the minds of outdoorspeople up and down the west coast. Her PCT role had been buried like a pebble under the duff on the forest floor, dwarfed by Clarke and the rest who followed, but we now know the origins of this world-famous trail lie with one ardent woman tramper.

Sometimes all it takes is one tall tree.

Barney Scout Mann is a thru-hiker and the author of Journeys North: The Pacific Crest Trail, published by Mountaineers Books. Journeys North tells the story of 6 PCT hikers – including Barney and his wife Sandy – as they face a once-in-a-generation drought and severe winter storms that test their will in this gripping adventure. Journeys North is a story of grit, compassion, and the relationships people forge when they strive toward a common goal. Get your copy at mountaineers.org/journeys-north.

This article originally appeared in our Fall 2021 issue of Mountaineer Magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, visit our magazine archive.

Barney Scout Mann

Barney Scout Mann