The Mountaineers is partnering with the Sacred Lands Conservancy, an Indigenous-led nonprofit with strong ties to the Lummi Nation, to produce a series of educational pieces on the importance of mindful recreation and how we can all develop deeper connections to the histories of our natural places. Tah-Mahs Ellie Kinley is a Lhaq’temish fisherwoman, an enrolled Lummi Nation tribal member, an elected member of Lummi Nation’s Fisheries and Natural Resource Commission, and President of the Sacred Lands Conservancy (SLC). We hope you enjoy this blog from her, written in collaboration with SLC’s Julie Trimingham, which shares history and context about the regional tribal treaties that allow us to live, work, and recreate on these lands and waters. - Conor Marshall, Advocacy & Engagement Manager

Many of us in Native tribes and nations hold our treaty rights dear, while many in non-tribal communities may be left wondering, What are these treaties, what are these rights, and what does any of this have to do with me? We are not scholars, and the words that follow are not a comprehensive explanation of treaties signed between the United States and Native sovereign nations. We wish to provide some background and context for our regional treaties here in the Pacific Northwest and share why they’re so important not only to Native peoples, but to all who live here.

What are Treaties?

Treaties are agreements between sovereign nations, and the United States Constitution recognizes treaties as “the supreme law of the land.” Back in the 1800s, the United States and Native peoples signed a number of treaties, including some that pertained to what was then called Washington Territory.

Broadly speaking, these Washington Territory treaties granted settlement rights to the United States and, in turn, promised protection of Native rights to fish, hunt, and conduct traditional activities in ancestral homelands. Furthermore, these treaties established lands exclusively for Native use (reservations), and promised ongoing healthcare, education, and other benefits to the signatory tribes.

The treaties don’t “belong” to Native people; all of us who live in the United States are party to the treaties and responsible for upholding them.

A Brief History of Regional Tribal Treaties

To understand the basics of how treaties work, it’s useful to know a bit of history. Since time immemorial, Native peoples have lived in what is now called North America. It’s estimated that there were over 1,000 distinct cultures, languages, and societies, and many millions of people here prior to European contact. The first few hundred years of colonization brought diseases, violence, and environmental degradations, the combined effects of which killed about 90% of the original Native American population.

As the United States became a nation, its government aimed to claim as much national territory as possible; the people who had always lived on - and were part of - the land were seen as an obstacle to this goal. The so-called Indian Wars - conflicts between colonists and any number of Native tribes - started in the 1600s and continued through the 1800s. The 1800s also saw President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act - resulting in the Trail of Tears - and other governmental efforts to forcibly take land from Native communities.

In the 1850s, the Oregon Territory was divided to create the Washington Territory, which included what is now Washington State, Idaho, and parts of Montana and Wyoming. Isaac Stevens became Territorial Governor of Washington, and began drawing up treaties so that he could secure rights to the land. He was seen as polarizing and effective. While he did manage to get these treaties signed in record time, securing land claims without going to war, he did so by intimidation, force, forging signatures, and martial law.

The Treaty of Point Elliott, the Treaty of Medicine Creek, and the Treaty of Point No Point cover territory in and around the Salish Sea. Along with those pertaining to the Olympic Peninsula and several east of the Cascade mountains, the land settlement treaties negotiated by Governor Stevens all contain similar language and intent. They established or promised reservation lands exclusively for Native use, and guaranteed the protection of signatory tribes’ rights to fish, hunt, and conduct traditional activities throughout their homelands. There were also provisions for payments, health care, education, and other services. With these treaties, Governor Stevens secured rights to over 100,000 square miles of Native lands across the Washington Territory.

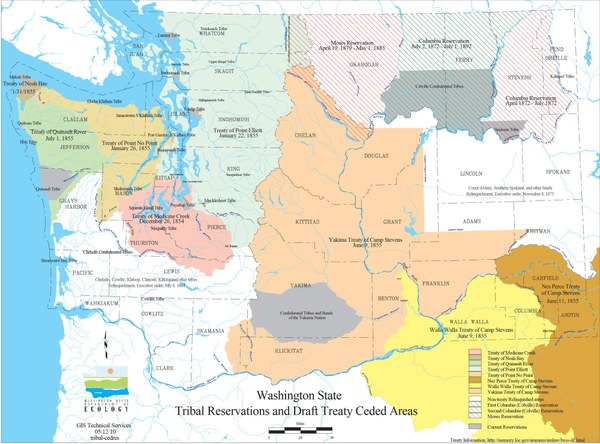

Washington state Tribal reservations and draft treaty ceded Areas map from the Washington Department of ecology. View a larger version of the map HERE.

Issues with the Treaty-making Process

While the premise of the treaties might seem fairly straightforward, the treaty-making process and subsequent follow-through was problematic. At one treaty council, witnesses reported that Stevens told his interpreter to “Tell the chiefs if they don’t sign this treaty they will walk in blood knee deep.” Differences in worldview, language, communication style, and intent also presented serious issues, each of which exacerbated the others.

Worldview

“We belong to the land; the land does not belong to us” is a popular way to express a basic Indigenous value. We see life in relationship, not ownership. The earth is alive, and we are all part of the same family. Those that swim, those that fly, those that walk on land, those that grow, the rocks, the stars, the water: all of this is our family. It is hard to imagine how, without even speaking the same language, Governor Stevens could communicate to our ancestors the Euro-American idea of land ownership and settlement, the idea that living lands would somehow “belong” to individuals.

Language

The treaties are lengthy legal documents written in a language (English) that many signatories did not speak or read. For instance, with the Point Elliott Treaty, Governor Stevens read the treaty aloud to the group of treaty signers. On the spot, an interpreter translated the Treaty into Chinook jargon, a trade language consisting of about fifty words. The resulting translation would have been clunky, incomplete, and inaccurate. The Chinook translation was then further translated by another interpreter into various dialects of Lushootseed, a language family of many (but not all) of the signatory tribes. It’s impossible to tell how well the intent and nuance of the written English treaty survived these translations.

Oral vs Written Communication

Native cultures are oral cultures. We take the spoken word to be binding and trustworthy: verbal agreements are honored. Governor Stevens was famous for making oral promises to the tribes, but then essentially breaking or changing those promises with whatever he wrote down in the treaty.

Intent

Many Euro-American people believed that both the treaties and the reservations would be temporary, that Native tribes and nations would soon disappear and then the United States would “rightfully” own all the land. In addition to outright violence and massacre, there were practices and policies designed to erase Native identities and people: relocation, assimilation, boarding schools, and starvation.

In Washington Territory, Governor Stevens did his part to further the practice of erasure by grouping disparate Native communities together and relocating them to a few reservations in territories perceived to be undesirable, and by breaking promises that proved inconvenient or unprofitable. For instance, the Nez Perce reservation was famously reduced by about 90 percent once gold was found on those lands.

The treaties were not designed with the best interests of Native Americans in mind. Rather, they were shortcuts to taking land without going to war. They were poorly explained and translated; signatures were often coerced. Many promises made were empty.

As Long as the Rivers Still Run

Despite the issues of the treaty-making process, our ancestors understood that signing the treaties was the way to avoid horrific strife and bloodshed. With remarkable wisdom and foresight, our ancestors also knew that the treaties would serve us well into the future by securing recognition of signatory tribes as distinct and sovereign political entities, and by protecting traditional cultural and spiritual lifeways.

Governor Stevens would often promote the treaties by saying that “as long as the mountain still stands and the rivers still run,” the United States would guarantee and defend our rights to fish and hunt in our various homelands. Each signatory tribe is unique, yet what Natives hold in common is our connection to Mother Earth. Our relationship to salmon and the other animals that nourish, teach, and sustain us is part of who we are; our ancestors made sure that this sacred connection was protected by international law. The rights to fish, hunt, and harvest require healthy fish runs, animal populations, and native habitats. Honoring treaty rights helps protect the lands, waters, life, and vitality of the places we now all call home.

In part two of this two-part blog series on tribal treaties, we examine:

- The ways in which the treaties have been interpreted

- The role treaties play today

- How treaties are good for the lands and waters of our shared home

- How you can help uphold the treaties by honoring and respecting tribal rights

Read more content from Sacred Lands Conservancy in this second post on tribal treaties our other pieces shared on our Honoring Native Lands and Peoples page.

Add a comment

Log in to add comments.Thank you for this article. I want to know more, and will make a better effort to learn what I can about this very important subject. I wish the tribes could regain rights to what was promised to them.

There is no commitment to Treaty Rights without a real commitment by the Organization to address climate change, both in organization practices, and active advocacy participation in Washington State regulatory activities restricting air pollution from the State's major polluters.

James, thank you for your comment and your passionate commitment to fighting the climate crisis. The Mountaineers is working to live out our organizational climate statement and net zero vision though ongoing efforts to reduce our organizational carbon footprint and by advocating for bold investments in climate solutions at the state and federal levels. https://www.mountaineers.org/blog/announcing-our-net-zero-vision

Sacred Lands Conservancy with Tah-Mahs Ellie Kinley

Sacred Lands Conservancy with Tah-Mahs Ellie Kinley