Rugged. Imposing. Breathtakingly beautiful and big enough to create its own weather patterns, Mount Rainier is the defining icon of the Pacific Northwest. While Mount Rainier National Park is generally known for this massive stratovolcano, the park is also home to nearly 100 other peaks where off-the-beaten-path adventurers can climb, scramble, and hike. When one visionary Mountaineer crafted a list of these objectives, he also created a community willing to go the extra mile for each other, even after someone is gone.

The Rainier 100 is a list of 100 high points found in and immediately adjacent to our state’s first national park. Mickey Eisenberg was the visionary behind the list, and the first person to visit all 100 peaks. He sought to bring visitors to the park for objectives other than Tahoma, and created the Rainier 100 to inspire and expand the park’s community.

Our Tacoma Branch Peak Pins provided the foundation for the list, specifically the pair of Irish Cabin awards which focus on peaks around The Mountaineers cabin property, together with the First and Second Peak awards for summiting peaks on the southern slopes and foothills of Mount Rainier. The peak pins comprise of about 50 summits, and to make up the rest of the list, Mickey selected only named peaks with a closed contour, meaning their hilltop or peak is marked on a topographic map. He eventually settled on 100, for a nice round number, nearly matching the exact number of peaks within park boundaries, though a few on the list are located just outside the park.

The list existed as a Word document for a while, but Gene Yore, another finisher and contributor to the guide, had ideas for sharing the information with more people. He envisioned the guide in e-book format to improve its share-ability and ease of use. Gene and Mickey worked with Mountaineers Books to digitally publish the guide, for which digital and mobile versions are available. It was the first foray into e-books and online publishing for Mountaineers Books, and the small amount of royalties were donated back to The Mountaineers.

After a while, Mickey and Gene started to believe the price of the book was a significant deterrent to sharing and disseminating information. Wanting to give access to everyone, they convinced Mountaineers Books to offer the guide for free. You can still access it for free on our website. Mickey recommends that you download the guide, “select where you’re thinking of going, print those two or three pages, and bring it with you.”

Inspiring a new community

Every year, in late winter through early spring, people in the 100 Peaks community gather to share stories and celebrate the new finishers of the year. These gatherings help new climbers get involved and interested in the list. “Beta from some of the climbs started circulating, especially at the "Spring Fling" as Gene called the annual 100 Peaks party,” Henry Romer, one of the most recent finishers of the 100, said. “The list created its own community of climbers who talked, shared, encouraged, and cheered. It was quite special and competitive – only in a very friendly way.”

This friendly competition is celebrated every year at the Spring Fling, where participants receive recognition for a variety of accomplishments on the list. The Rainier 100 doesn’t only award for finishing all 100; smaller sections of the list also garner awards at 25-peak increments. Finishing the 76 scrambles or completing the 15 hikes on the list will also earn medals. Five medallions in total are given, each with a matching, color-coded certificate.

Those who have completed the 100 are not only proud of the accomplishment, but also in complete awe of the park. “It’s a remarkable treasure,” Mickey said. “Everybody knows Rainier is a treasure, but [the park] has peak upon peak of treasures.”

“This is a really worthwhile thing to do,” Henry said. “It pulled me back into climbing.”

A laudable achievement

The 100 Peaks community shares a lot of love for the list, but that doesn’t mean it’s devoid of challenging summits. Pigeon Peak, for example, seems near-universally despised. “It was horrendous. Not because of the technical difficulties, it’s just a total brush-bash, climbing over logs and fording a river,” Mickey said. To top it all off, the view is reportedly quite underwhelming (think non-existent). “It's not a very heroic peak.”

Henry disagrees when it comes to some of the criticisms, but acknowledges that success often hinges on route-finding and planning, solid navigation skills, and good conditions. He believes climbers’ favorites are generally the result of the confluence of those circumstances, with the disliked routes often being the trips where none of those things came together for the group.

Solid navigation skills are especially critical, as Henry emphasized. “It's not five miles through the woods to get to this spot. It's the three quarters of a mile, somehow up this ridge and gully, without sight lines,” he said. Though it may require pre-developed navigation skills, Henry said that there is a lot of learning that goes on throughout the 100 routes as well. “In finishing the 100 hundred peaks, you really start to get this good feel for off-trail navigation in the Cascades,” he said. “It’s pretty cool.”

And Henry would know. Conditions on some of his climbs have resulted in less than agreeable circumstances. Henry and Gene experienced an unplanned bivouac on Third Mother, a route with five independent navigation cruxes. It wasn’t a dire situation by any means, but the bivouac became necessary when they found themselves still on-route late into the evening. You won’t hear any complaining from Henry though. “I tell people I’ve had worst nights on a 747,” he said.

The trail to 100

The group is close, made up of current climbers, finishers, and friends. Henry said he and others routinely check Peakbagger, a website used to track summits and share trip reports, each Monday to see who had climbed what, and how. “The community effort to help everybody find the hidden secrets is tremendous,” he said. “You know, that's something you don't often run into.”

The community is large enough that climbers inevitably run into other 100 Peakers around the park, as Henry did sometimes. On Meany Crest in late August 2015, Henry was headed up to the base of the climb and he happened upon two people at their camp. Henry introduced himself to the other men: Tim Hagan and Kim Hood. Tim, a member of The Mountaineers since 1978, was working on the 100 Peaks and nearing completion, and Henry recognized his name from the Frontrunner’s List on Peakbagger, the official tracker for who is closest to finishing the 100.

Tim Hagan during an attempt on one of the 100 Peaks. Photo by Kim Hood.

Tim Hagan during an attempt on one of the 100 Peaks. Photo by Kim Hood.

They talked for a while. Tim had just finished peak 97, with three left, and for Henry, Meany was going to be number 71. Eventually, Henry headed on towards Meany Crest while Tim and Kim stayed to camp and climb Whitman Crest the next morning.

One month later, Tim passed away after a fall on Sluiskin Chief, his 99th peak, with only one left to go.

Kim was one of Tim’s closest climbing partners for decades. They met in the 80s on Aconcagua during a trip together connected by a group of mutual climbing partners. “For some reason, Tim and I, we just hit it off and we kind of hike at the same pace. From that point on, we became each other's climbing partner,” Kim said. They climbed around the world together, and Kim completed many of the 100 with Tim. “He was one of these guys that could kick steps all day long. I don’t know how many times I would be whupped and he would just say ‘it’s right there’ and keep going.” Kim said. “It’s kind of like I was guilted into following.”

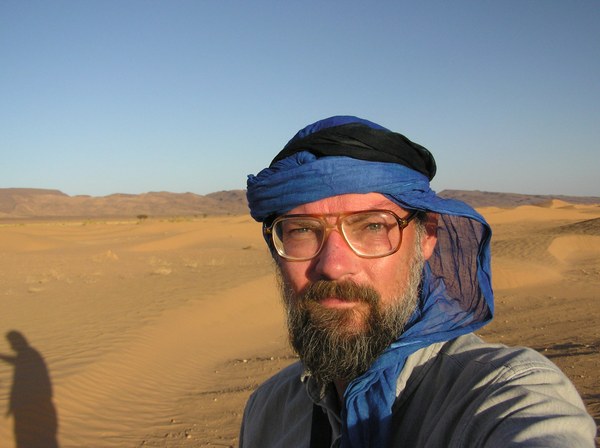

Kim and Tim traveled to Antarctica and rode camels into the deserts of northern Africa. In 2008 they visited the four Hindu Temples of the Char Dham in India. In 2010 they hiked through Nepal into Tibet. On one trip to India in 2008, Kim and Tim ran into Conrad Anker as he returned to a lower camp from an attempt on Meru with Jimmy Chin and Renan Ozturk. After the group continued on, the pair mused whether or not it had been a group of famous climbers.

Tim never stopped, with lofty goals for himself in both travels and climbing. “Before he even got on the [Rainier] 100, he had a personal goal of climbing 100 peaks of their own prominence in one summer,” Kim Said. “And he did that easily. He was constantly out in the hills.”

An honorable finish

In late July 2018, on the way to Panhandle Gap for his final climb, Henry ran into two climbers who were heading down from Cowlitz Main. One of the two men explained they had climbed it to honor their late friend, who had passed away right before completing this final climb on his 100 Peaks list. They were descending after summiting to spread his ashes.

“You’re Kim Hood,” Henry said, mentioning their meeting at Meany Crest in 2015. They chatted for a while, and Henry explained that he was headed up for the same final climb. “Well, it looks like Tim may have beat you to the 100!” Kim said to Henry in a moment of shared appreciation."

Tim’s accomplishments through a lifetime of climbing are awe-inspiring, with summits of peaks like the 20,561-foot Volcán Chimborazo, 18,491-foot Pico de Orizaba in Mexico, and the 17,575-foot Gokyo Ri in Nepal. His wish list on Peakbagger contains 16 peaks in Scotland, where he studied engineering, and became involved in the climbing club. He climbed on every continent except Australia. He added nearly 30 new peaks from all over the world to the website’s database, and his ascent list (the summits he’s tracked on the website) shows over 1,400 climbs. His profile links to a Flickr photo library, displaying many of his climbs around Mount Rainier and the world.

Tim’s name is still in the top spot on the Frontrunner’s List. His Peakbagger profile reads “Tim was a dedicated Seattle-area climber with significant international experience and a passion for peakbagging. He helped out with many corrections to this website. He had just finished his 99th peak on the "100 Peaks at Mount Rainer National Park" list when he tragically perished in a fall. He was a kind and generous soul who will be missed by all who knew him.” Thanks to Mickey, others can still walk in his footsteps to honor his memory.

Tim Hagan in the deserts of Northern Africa. Photo by Kim Hood.

Tim Hagan in the deserts of Northern Africa. Photo by Kim Hood.

This article originally appeared in our Summer 2019 issue of Mountaineer Magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, click here.

Trevor Dickie

Trevor Dickie