by Suzanne Gerber, Mountaineers Publications Manager

Some journeys begin with a single step — and some with years of planning and research, months of training, and weeks of food and logistics preparation. Evan’s 2016 summit of Denali falls in the latter category, but then so do most successful expeditions.

For Evan, this journey was sparked by another expedition six years earlier. In 2010, Evan joined a Mountaineers Global Adventure to trek the Dhaulagiri circuit in Nepal, led by Craig Miller. This 21-day trek encircled Dhaulagiri, the seventh highest summit in the world at 26,795 feet. It included the French Col, a 17,700-foot (5,400m) pass and overnights at several base camps. While sitting at the Dhaulagiri base camp and looking up at the snow-covered peak towering overhead, Evan pondered other expeditions he might go on in the future. He was considering climbing one of the many peaks in the Himalayas when Craig recommended Denali.

Planning

In 2011, Evan took the Denali Expedition Planning Seminar, led by Jeff Bowman (who summited Denali in 2003) at The Mountaineers Seattle Program Center. It’s a course that goes over all the logistics for tackling this peak. Denali is the third tallest of the famous “Seven Summits” — an ambitious list for seasoned and professional climbers that is made up of the tallest peak on every continent from Mount Everest for Asia to Mount Kilimanjaro for Africa.

The Denali Expedition Planning Seminar included three evening lectures and one full-day clinic. It went over equipment, planning and logistics, preventing and dealing with altitude sickness, effective team dynamics, route planning, and crevasse rescue with a sled – which was practiced over the north wall of The Mountaineers Seattle Program Center. The mountaineering sled (also called a pulk) was packed with sleeping bags and coats to simulate bulk, but not heavily weighted. The point was to experience rope handling over a simulated crevasse.

This wasn’t Evan’s first exposure to technical gear and training. A long-time Mountaineers member, Evan graduated the Basic Climbing Course in 2006 (Everett branch) and enrolled in the Intermediate Climbing Course a few years later. He’s also taken navigation, first aid, avalanche, ski, scrambling, snow camping, sport climbing, ice climbing, self-rescue courses — and even a yoga for climbers course. He volunteers as a Mountaineers ski, scramble, snowshoe and hike leader.

Rent or Buy

One of the first questions an expedition climber asks themselves is whether to rent or buy gear - or just rent some and buy the rest? The gear can be the most expensive part of the expedition — and some of it is needed very little, depending on one’s goals. Evan decided to buy all his gear, including the pulk (a mountaineering sled), so that he was able to train with it in advance. This decision also increases the cost of checked bags. Reaching the 50lb maximum per bag limit is easy to do when your luggage includes ice axes, tents, snowshoes, stoves and pounds of food.

As an avid backcountry skier, Evan was considering skiing down Denali, which would have added a few more pieces of gear to the mix. But that would mean putting together a team of fellow skiers and the group that came together opted to snowshoe. They ended up with about 550bs of luggage — divided into four bags. And not all of it was waiting for them when they arrived in Anchorage. The delayed luggage made it on the next flight, but with the anticipation of their expedition and a pre-scheduled ground taxi waiting, the trip started off with some stress.

Team Salish

Evan was originally hoping to climb Denali in 2013, but due to life circumstances and expenses, the trip was put on hold. An official climbing team finally came together in early March of 2016. It consisted of Anthony White, the youngest, a 21-year old student at Washington State University; Endo The Timber, a Chinese-born Canadian police officer; Jim Freeburg, a government insurance advisor; and Evan, who works as an IT analyst. They named themselves Team Salish.

A fifth team member, Louis Coglas, was also planning to join, but had to pull out just three days prior to the trip. This could have caused a major setback because Louis was providing important shared gear, including a two-person North Face tent — but he generously let the team pick up the gear and use it without him to avoid a last-minute scramble.

Training

The physical training for Evan involved weekend climbs, backpacks, and weighted hikes. He wasn’t able to take off work because he had to save vacation time for the expedition itself. He pushed himself hard, and ended up pulling a muscle in his back, so physical therapy two times a week became part of the training as well.

Jim and Evan also spent several weekends hiking with each other — and Endo, Anthony, and Jim had all climbed together previously. But as a team, the first time all four of them climbed together was Denali. They didn’t have a chance to do a dry-run on Baker or Rainier. This meant that they had limited experience bonding as a group to work out dynamics and roles.

The Climb

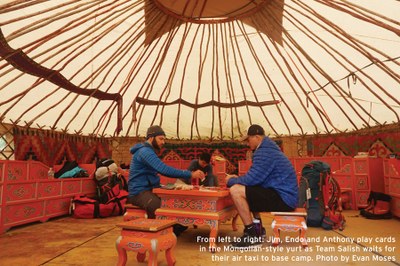

The team flew to Anchorage, Alaska where they waited for a smaller plane along with other climbing groups through Talkeetna Air Taxi. They had the choice of staying in a bunkhouse, a Mongolian-style yurt, or informal carport sheds while sorting gear and getting ready. Every team got flags and wands that they used to identify their gear and mark where they buried their caches. This was where Evan’s team members rented their sleds.

It was a hurry-up-and-wait kind of environment as the smaller planes flew on the whim of good weather windows and could start as early as 6am. Evan and the rest of Team Salish chose to stay in a Mongolian-style yurt while they waited. They caught a flight at 2pm on the third day. This also gave them time to wait things out in the wet Alaskan weather and go to house parties with the local aircrew who play beach volleyball in 50-degree rainy weather. The air taxi took them over to the Kahiltna Glacier Airport – a makeshift landing area on solid ice/snow. This is also the first base camp for Denali, at 7,200 feet.

Team Salish camped at four more base camps —7,800, 11,000, 14,000 and 17,000 feet. Traveling expedition-style, they also left caches at 9,000, 13,000 and 16,000 feet. They climbed ahead and buried caches in the snow, marked with “Team Salish” wands, and acclimatized by spending nights at the base camps just below each cache.

A surprising amount needs to be done at each camp — from boiling water, cleaning, and cooking, to organizing supplies/making sure nothing is left behind or gets lost in the snow. This is the place where the limited time for team building became noticeable. Styles of camping and roles were not established and didn’t always mesh well — but aside from a lost carabineer and a stove catching fire, Team Salish was a well-organized group. Witnessing a Japanese team of two lose their tent to the wind put things in perspective as to what a bad day could look like.

On the other side of the scale was a professionally organized Korean climbing team of nine who had their own base camp manager who stayed at the 14,000-foot base camp with a radio and extra gear. Meeting them was one of the highlights of the trip for Evan. They were helpful and generous — fully embracing the spirit of mountaineering. They shared food, kimchi, tea, and hot coconut milk with Evan’s team.

The Summit Proposal

The true highlight of the trip was summiting. Evan reached the top on June 2. He was there just long enough to get a quick snapshot holding up a sign with a marriage proposal written on it for his (then) girlfriend, Tara Boucher (fiancée as of the printed publication of this, and now, wife). He and his team didn’t make it up as one – there were complications involving taking care of Anthony, who at about 18,000 feet came down quickly with moderate altitude mountain sickness. Jim, the team’s leader, decided to descend with him back to advance base camp at 17,000-feet, while Endo and Evan continued to the summit. Jim later summited with the Korean team.

Afterwards, Team Salish descended back to the 14,000-foot base camp. They truly lucked out with the weather. Some teams have to wait days or even weeks at high base camp for a chance to summit, and weather can change drastically and unexpectedly at that altitude. Many climbers were unsuccessful during the time period of Evan’s expedition due to weather at 17,000 feet and above. Other parties experienced severe set-backs including snow-blindness cases, altitude sickness, and even a fatal accident that required helicopter support.

When everyone got back to the 14,000-foot base camp, they were invited over to the tent of the Korean team for a barbeque. The two teams had been silently cheering one another on as they tackled the same mountain and it was a joy to celebrate together over cans of beer, kimchi, delicious steaks, and hot hand warmers.

From start to finish, Team Salish’s expedition lasted 16 days (Evan and Endo summited on the 11th day). They had prepared to spend up to three and half weeks on the mountain and so they had plenty of food to spare — which they left with other teams who were on their way up.

The team returned to civilization, and Jim and Evan stayed in Alaska for a bonus week, while Endo and Anthony flew back to Seattle. Endo traveled to Pakistan just a week and half later to climb another 8,000-meter peak on his own after the Denali warm-up.

Jim and Evan acted as Alaskan tourists and ate large pancake breakfasts while they waited for their girlfriends to fly up to join them. From there, each couple went on their own adventures of icebergs, glaciers, flight tours, and seaside villages.

As they visited the touristy-side of Anchorage and the Denali National Park, Tara proudly shared with fellow tourists that her boyfriend had just come down from the peak of that mountain they were all admiring.

Evan waited three months to present the photo of his note at the summit to Tara. He wanted the proposal to be perfect. He surprised her with a three-day weekend cruise around the San Juan Islands, and they made the engagement official on September 4, 2016.

Suzanne Gerber

Suzanne Gerber