“And they said it wouldn’t last.”

Both snappily dressed in robin’s egg blue, two octogenarians sit perched in their warmly-decorated living room, eyes glittering. Their home is dotted with family photos, historic photographs, and art collected on far-away adventures.

Over the decades, Billee and Jack Brown have raised six children and enjoyed 18 grandchildren and 28 great-grandchildren. They’ve climbed and scrambled dozens of mountains together, from the volcanoes of Washington to the peaks of Nepal. They are the second of five generations in their family to have explored the mountains of the Northwest, with roots going back to the early days of The Mountaineers. The love between them is palpable.

What kind of life has led to such a rich, enduring relationship? It all started in Chicago over 70 years ago.

Young love

Billee and Jack met in July of 1948. He had just turned 16, and she was 15 ½ and new to town, having just moved from Tacoma following her parents’ divorce. They both happened to be in a group down by the local drugstore, Billee standing on her head on the corner as a party trick. Immediately smitten, Jack offered to give her a ride home on his bicycle’s handlebars. “He rode me home, swerving as he went down the street like he was going to hit the parked cars trying to see if I would scream…but I didn’t,” Billee said.

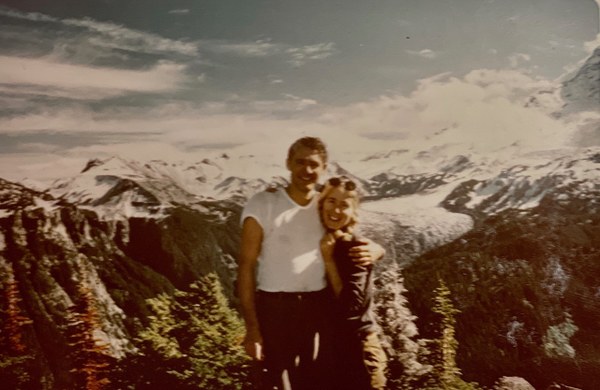

Jack and Billee on top of Third Mother Mountain in October 1971, celebrating the completion of the 24th peak to qualify for what is now known as the Irish Cabin Second Twelve pins.

Jack and Billee on top of Third Mother Mountain in October 1971, celebrating the completion of the 24th peak to qualify for what is now known as the Irish Cabin Second Twelve pins.

“She wasn’t like other girls I’d met in high school,” said Jack. “She was… controlled.”

They began spending more time together, and after a month and a half Jack mustered up enough courage to ask her to go steady. Always practical, Billee replied, “No. I don’t believe in going steady unless it’s a preliminary to getting engaged and married.”

Jack sat silently, tinkering on his bike. Finally he replied, “Ok, I understand that.”

The next few years were a whirlwind of overcoming parental disapproval, loss of college funds, Jack going off to college, and more than one attempt to break them apart - all culminating in a small wedding in 1951, in a little church just outside of Atlanta. They were married at 18 and 19.

In college at Georgia Tech, Jack studied architecture, worked part-time, and participated in ROTC to earn extra money. Billee took care of their growing family and babysat, watching children for military families who lived near them in campus housing. “When our second son was two weeks old, I took in a six-month old and a two-year old. We needed the money, and I was healthy and doing well. So that’s what we did.”

When Jack graduated from Georgia Tech, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the army and became an army aviator. His architecture degree also caught the eye of a commanding officer. “I designed dormitories. I designed chairs. I designed test facilities for the jet engines because we didn't have jet helicopters at that time. And everything was done by hand.” After spending several years flying in the army, he transitioned his career back to architecture, while Billee raised their now six children in a bustling household.

Recalling those hard-working early years, Billee said, “I have a degree from Georgia Tech as well, also presented to me by the college: ‘Mistress of Patience in Husband Engineering.’ I was glad I was a stay-at-home mom. It was my choice, I didn’t have to do it.”

Growing up with The Mountaineers

After moving to Washington, Billee and Jack were introduced to The Mountaineers by Billee’s father, Eugene Fauré. They found themselves going from house to house, meeting Mountaineers heavyweights like environmentalist Helen Engle and Mountaineers Books author Harvey Manning. The big draw for the young family was the Camp Crafters – a program designed to get kids outside to explore the natural world. It utilized our cabins and was full of summer camp-like activities, including hiking, campfires, and singing camp songs. They also spent a significant amount of their time in Mt. Rainier National Park. “It was our kids’ playground,” said Jack.

Billee carries little Eric in her backpack on a hike.

Their social lives revolved around the Camp Crafters when their children were young, a blur of outdoor excursions, parties, and adventures. Everything from Thanksgiving dinners to Helen Engle’s annual May Day parties were part of the young family’s lives.

Their daughter Sandra warmly recalled days spent in the Irish Cabin, a fixture of their time in The Mountaineers: “I loved going there in all seasons, though summers camping there were the best. I remember helping clean the cabin, getting out the mattresses, huddling around the wood stoves, looking at the books in the old bookcases, and exploring the trails. Preparing for the Thanksgiving feast, I watched the older women working the big stoves, in awe over their skill cooking pies and turkeys in those massive ovens. We took many hikes around the cabin, always led by experienced hikers who taught me that age doesn’t matter.”

The children grew rapidly, and as they aged out of the song-and-dance days of the Camp Crafters they began to take on more daring excursions.

Billee and Jack skiing with all six children at Paradise, 1967.

Billee and Jack skiing with all six children at Paradise, 1967.

Four of their children took our Basic Climbing Course, their sons Mike and Steve diving headfirst into the sport from a young page. Their eldest, Mike, took Basic when he was 14 and began Intermediate at 15, leading climbs for Basic by the time he was 16. He was a member of the Tacoma Climbing Committee his junior and senior years of high school, while also organizing field trips for Intermediate and serving as chair of the Junior Mountaineers. “The amazing feature of my involvement with The Mountaineers was that my age had no bearing on the responsibilities and opportunities available to me. I was treated as an individual whose worth was measured and valued on the basis of my knowledge, skills, and maturity. I doubt that similar experiences would have been possible in any other organization,” said Mike.

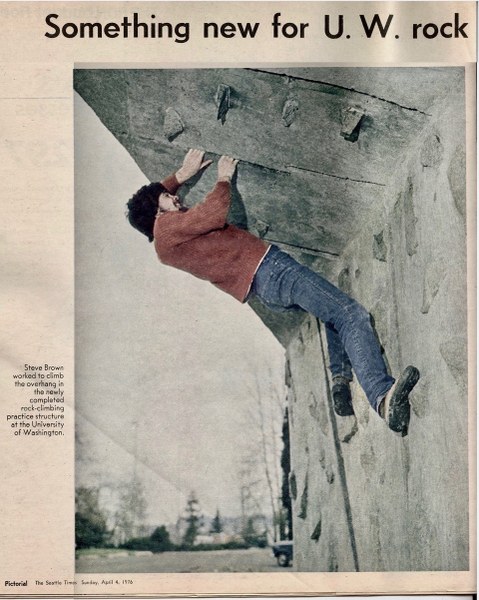

Steve also had the opportunity to take our Basic and Intermediate climbing courses, volunteering as an instructor in late high school as Mike had done. When the brothers went off to college, they were heavily involved in the creation of Husky Rock – a 30-foot-tall man-made bouldering rock on the outskirts of campus, put up in the mid-1970s as a way to placate the college climbers scaling the walls of academic buildings. A local landmark and one of the first fabricated climbing walls in the U.S., Husky Rock is still utilized by climbers today.

Steve featured in The Seattle Times as he tests out the new climbing structure, Husky Rock.

Steve featured in The Seattle Times as he tests out the new climbing structure, Husky Rock.

Recalling the impact The Mountaineers had on their children, Billee shared what it was like to raise a family of six in the outdoors:

“All the years our kids were growing up, and for a little while after, The Mountaineers were very definitely the center of our activities. I think raising kids with an appreciation for the outdoors, and with knowledge and expertise of how to do things in the mountains, is very important. And I think it leads to a lot of life skills. We taught them from the very beginning to be responsible for their actions. It started with how we raised them, and it continued with their training in The Mountaineers.”

Alpine parents

However, Billee and Jack weren’t ones to be left behind. Both took our Basic Climbing Course, taking turns so that someone was always around to watch the children. Jack went on to take Intermediate, becoming an avid mountaineer. He climbed Mt. Rainier a total of seven times – twice with Billee, who once bivvied with him and their sons, Cliff and Eric, in the crater so that they might enjoy sunrise from 14,411 feet.

Both Jack and Billee have their Seattle Branch Six Majors pins, awarded to those members who have climbed the six tallest peaks in Washington – available only to those who climbed Mt. St. Helens before she blew her top in 1980. They also have the Tacoma Branch Irish Cabin Second Twelve pins, given to members who have scrambled a staggering 24 peaks near our Irish Cabin property and the Carbon River entrance to Mount Rainier National Park.

Jack in particular climbed extensively, achieving the first winter ascent of the Gibraltar Route on Mt. Rainier with Stan Engle in the late 1960s. He was known for carrying heavy camera equipment on most of his climbs, and was involved in Tacoma Mountain Rescue. He and Mike would go out on rescue missions, Billee manning the phones to call climbers in the middle of the night to let them know that they were needed.

The family on a backpacking trip in the late 1970s. From L-R: Steve’s wife Teresa, Billee, Steve, Eric, and Jack.

The family on a backpacking trip in the late 1970s. From L-R: Steve’s wife Teresa, Billee, Steve, Eric, and Jack.

As Jack was a pilot, he also played a special role in the construction of the mountain rescue hut perched on Mt. Rainier’s Steamboat Prow.

“I flew a number of trips dropping building supplies down. Sand, concrete, and whatever else they needed. We would stuff it inside a truck tire, using wire to keep it all in. Then Larry Haggerness would signal when we needed to drop it. The last load we dropped (we had a parachute), was a case of beer. So we were really popular.”

The old goat

It could be argued that one person is responsible for Billee, Jack, and their brood’s heavy involvement in The Mountaineers: Eugene Fauré, Billee’s father. Called Gene by most, he had a strong personality, and can be credited with more than one introduction to our organization.

“He ran into two young climbers one day, with a clothesline ‘rope’ tied around their waists. He walked up to them and said, ‘why don’t you go to The Mountaineers and learn how to do it right!’ And they did. Their names were Jim and Lou Whittaker,” recounted Jack.

“When Jim came back from his climb of Everest, he spoke at PLU. And the first thing he did in the introduction of his speech was to give my dad credit for getting them started the right way,” said Billee.

Gene’s involvement in The Mountaineers started in 1948. He dove head-first into the organization, quickly making friends with key members – Wolf Bauer, Omi Daiber, Shortie Williams, Larry Haggerness, Harvey Manning, and more. Having taken both our Basic and Intermediate courses, Gene soon began instructing and went on to help with the formation of Tacoma Mountain Rescue, one of the earliest U.S. mountain rescue teams. He even contributed to the first edition of The Freedom of the Hills, our seminal mountaineering text. Though not as well-known as his counterparts, Gene contributed years of his life to The Mountaineers and had a hand in pivotal developments.

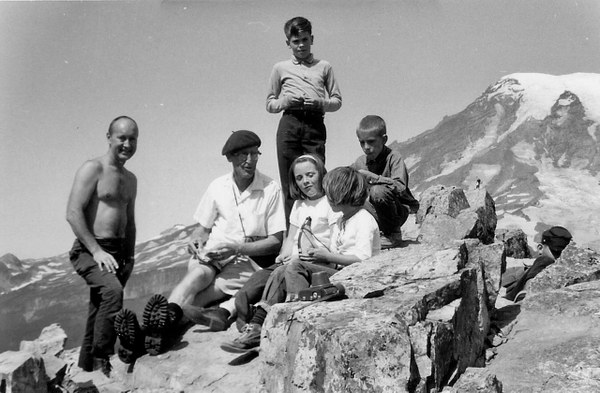

Gene sports a beret as he spends time with his grandchildren on Pinnacle Peak, 1960s.

Gene sports a beret as he spends time with his grandchildren on Pinnacle Peak, 1960s.

However, he was not known for his gentle demeanor. “He could be rather brutal,” joked Jack.

“He knew all the old guys – even though he was only in his 60s at the time he was already known as ‘the old goat,’” said Billee.

Gene was a long-time smoker and spent his career as a chemist at the local smelter, and upon retiring at 65 had grand plans to climb across Europe. However, that year he received fatal news: cancer. He had months to live.

Always direct, Gene set to work alerting those he knew best of his diagnosis. Billee accompanied her father as he returned his newly-purchased climbing gear to REI and made his rounds, delivering the news in his usual style.

“He would arrive at someone’s house with an old down sleeping bag, inside of which he’d rolled up a bottle of Old Grand-Dad [whiskey]. His way of greeting people was rolling out the bag and saying, ‘let’s have a drink. I got somethin’ to tell ya – I’m dying,’” recounted Billee.

“He sure was a real character,” laughed Jack.

A key figure in both The Mountaineers and his grandchildren’s lives, “the old goat” was sorely missed from the mountains when he finally hung up his ice axe.

Later years

Though their lives raising children and working were brutally busy, Billee and Jack appeared to only speed up once their chicks flew the coup. Together they’ve rafted the Grand Canyon and the Upper Apurímac River in Peru, kayaked in Iceland, canoed the South Nahanni River in Canada’s Northwest Territories, and trekked through New Zealand and through Nepal – twice. On a trip to Africa, they both summited Kilimanjaro.

Although their involvement in The Mountaineers faded once their children were grown, most of the trips they took were with friends made in our community – friends they still retain to this day.

“Friends that we met through The Mountaineers are our lifetime friends. Every Sunday morning, there’s a group 10-13 of us that meet for breakfast. Almost all of them had been Mountaineers,” said Jack.

Now at 88 and 89, they still value physical activity and get out for regular walks and hikes, utilizing their Nordic Track on rainy Tacoma days. Jack still runs, participating in races when he can.

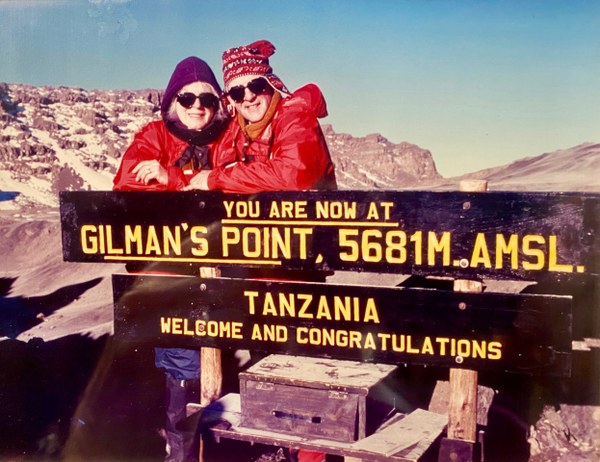

Billee and Jack on the crater rim of Mt. Kilimanjaro before Jack continued on to the summit, January 2000. They were 67 years old.

Billee and Jack on the crater rim of Mt. Kilimanjaro before Jack continued on to the summit, January 2000. They were 67 years old.

They take great joy in their large family, down to the littlest great-grandchildren that are just exploring the outdoors. Recalling a hike with two of their great-grandkids, Billee was delighted by one’s budding interest as a naturalist.

“The five-year-old, he talked the whole time we were going up the trails. ‘Oh, that's a fir tree. It keeps its needles on all year long. And birds like to make their nests up there.’ He’d just chatter, chatter, chatter, chatter… talked the whole time! He was just incredible.”

Sitting in their living room, you get the impression that what you see in front of you is their lives’ work. To exude joy at this age isn’t something you stumble into. From their days as penniless 19-year-old parents to exploring Nepal in retirement, Billee and Jack seem to have carried two things with them always – love and respect. For their family, for their community, for the natural world, and for each other.

Here's hoping we all might be so lucky.

A four generation hike above Paradise. From L-R: Jack, Billee, their great-grandson Bennett, Rich’s wife Davida, great-granddaughter Abigail, grandson Rich, Steve’s wife Teresa, and son Steve.

A four generation hike above Paradise. From L-R: Jack, Billee, their great-grandson Bennett, Rich’s wife Davida, great-granddaughter Abigail, grandson Rich, Steve’s wife Teresa, and son Steve.

This article originally appeared in our Fall 2021 issue of Mountaineer Magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, visit our magazine archive.

Hailey Oppelt

Hailey Oppelt