Whenever you set out on a trail, take time to appreciate its construction. A a complimentary piece to "Lightly on the Land" published our summer 2019 magazine, here we share some key trail features to look out for courtesy of stewardship expert and Mountaineers Books author Bob Birkby:

Location

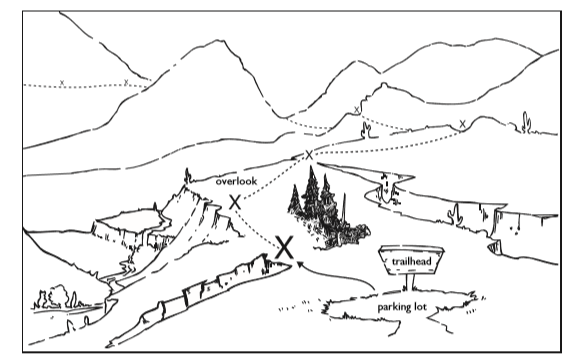

Why does the trail go where it goes? Designers explore an area in search of control points – over a pass, below a rock outcropping, along the edge of a meadow – places a trail must go in order to travel from a trailhead to a destination. Connecting those points at a reasonable grade becomes the route.

from LIGHTLY ON THE LAND.

from LIGHTLY ON THE LAND.

Grade

The steepness of a trail is measured with a tool called a clinometer and read out as “percent of grade.” That comes from the equation rise over run equals percent of grade where run is the distance traveled (say, 100 feet) divided into the rise, or elevation gained over that distance (say, 8 feet):

8 feet of rise ÷ 100 feet of run = .08% grade

For hikers, 8%-15% is comfortable grade. Steeper than that and going up becomes more challenging, and water coming down has a better chance of causing erosion. Trails that switchback up a steep ascent can maintain a reasonable grade.

By sighting through a clinometer with both eyes open, the incremental scales inside the instrument and the landscape you're viewing beyond will both be visible.

By sighting through a clinometer with both eyes open, the incremental scales inside the instrument and the landscape you're viewing beyond will both be visible.

FROM LIGHTLY ON THE LAND

FROM LIGHTLY ON THE LAND

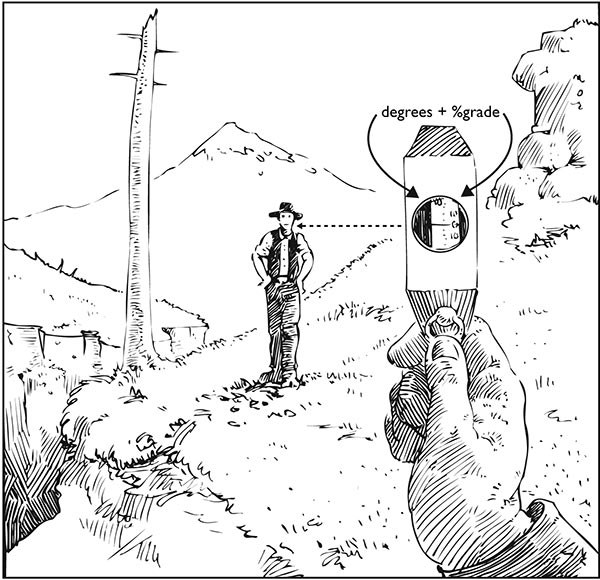

Tread

The walking surface of a trail. Ideally, it is slightly out sloped - tipped so that rain water and snowmelt drain off quickly rather than flowing down the trail and causing erosion. Tread maintenance often involves removing buildup of soil and forest debris from the outside edge (where it is called berm) and the inside edge (slough). A travel corridor cleared of brush on either side and above the tread provides clearance for travelers.

FROM LIGHTLY ON THE LAND.

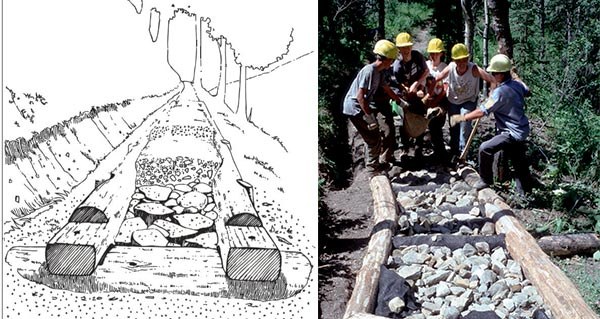

Turnpike

Turnpikes raise the tread to get the walking surface above a boggy area. Logs or rocks installed on either side hold layers of rock and gravel in place.

Left: FROM LIGHTLY ON THE LAND. Right: Constructing a Turnpike.

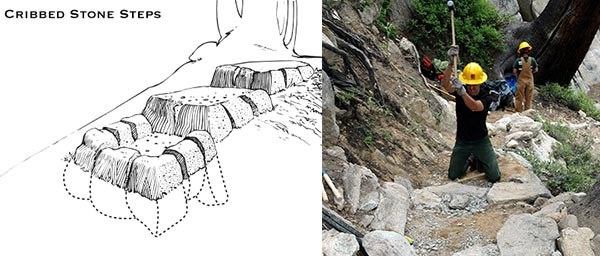

Staircases

Stairs can be ideal solutions for getting hikers up short, steep ascents. With rock bars and coordination, a crew can leverage rocks of several hundred pounds into position and lock them together for durability and use. Cribs of natural or milled timber can be set in a slope and then filled with gravel to form walking surfaces.

Left: FROM LIGHTLY ON THE LAND. Right: Constructing a rock step on the John muir Trail in the high sierra.

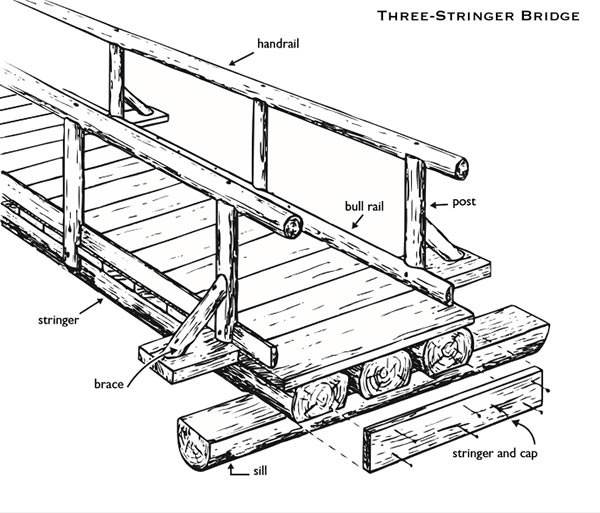

Bridges

Consider where a rustic bridge is placed – usually a narrow point in a stream, ideally with rock outcroppings as immovable foundations. Look underneath and you’ll probably find sill logs parallel to the stream. The stringer logs that cross the water rest on the sills. Bull rails on either side of the decking prevent the feet of hikers and horses from slipping off the edges.

FROM LIGHTLY ON THE LAND.

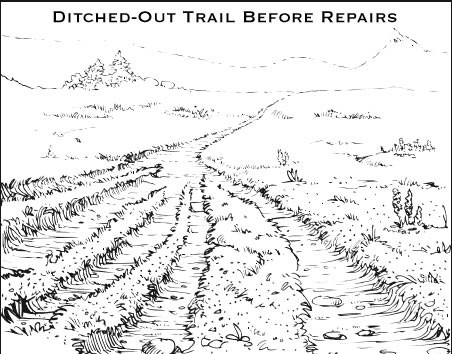

Site Restoration

When the restoration of a damaged campsite or trail is completed, you’re unlikely to notice it at all. Repairing a beaten-down campsite or abandoned trail often begins by loosening the soil so that new vegetation can take root. You might see an area covered with mulch matting that protects and nourishes new growth. Crews sometimes install rocks, stumps, and other natural items to blend repaired locations into the background and deter future use.

An ever-widening braid of beaten-down trails is a common place problem in meadows and alpine tundra. FROM LIGHTLY ON THE LAND.

Close off unwanted trails and make the remaining tread the most inviting route for travelers. FROM LIGHTLY ON THE LAND.

Close off unwanted trails and make the remaining tread the most inviting route for travelers. FROM LIGHTLY ON THE LAND.

Add a comment

Log in to add comments.The book is my go to source for all work ido on trails.

Bob Birkby

Bob Birkby