The River and the Bay

The wilderness was vast and seemingly empty, but as I motored along I was nestled in a glowing cocoon of technological magic. Not one but two Garmin GPS chart plotters silently communed with the satellites overhead. My radar system could penetrate the thickest of fogs, though the day’s clear skies and sunshine made the prospect unlikely. My depth-sounder pinged sonar pulses off the rocks below, and I even carried something called, in bureaucratese, an Emergency Position Indicating Rescue Beacon, or, more jauntily, an EPIRB. Supposedly it would, at the panicked touch of a button, supply my coordinates and credit card information to the nearest helicopter rescue service.

I may not have known what I was doing, but I could tell you exactly where I was doing it.

Even with all this technology, the way forward seemed little more than guesswork. I quickly discovered my fancy electronic charts displayed nothing about the Nelson River this far inland, and I hadn’t thought to bring along a topographical map that might show the river’s contours. Aside from the twenty-foot-high banks, there wasn’t much in the way of topography, anyway—just hundreds of miles of flat, buggy forest that eventually gave way to flat, buggy tundra.

I motored along blindly, using my depth-sounder to steer clear of submerged rocks and the irregular shelves of hard granite, invisible in the milky green water. Every time I passed over a shallow spot, I unconsciously held my breath and lifted my feet off the floor, as if that was going to help.

When I reached the deeper main channel, a strong current swept C-Sick downriver. I was soon traveling at more than nine knots, nearly eleven miles per hour, with my engines hardly ticking above an idle. There was no turning back. I couldn’t fight my way back upriver against this current even if I wanted to. Like it or not, I was on this ride to the end, seventy-five miles to the Bay and whatever came after. I let go of that unhelpful thought and settled in as best I could, relaxing enough to enjoy the warm sun and a gentle breeze blowing upriver. It occurred to me that I should remember this feeling—the beginning-ness of it. Lost in the swirl of planning and motion and action, I had spent weeks plunging blindly ahead without ever taking time to appreciate the moments as they passed. I took out my cameras and shot a few desultory frames to record the scene. Silty river, sky of blue, forest green. But for the most part I simply basked in the fleeting minutes when I might finally breathe in and out and slow the passage of time.

Gradually the river grew wider. In the late afternoon, I rounded a bend and suddenly the steep banks and endless green forest gave way to . . . nothing. Off in the distance, I could just make out the featureless horizon, and beyond it, the Bay.

I laughed out loud. It was all going to be okay, after all.

And then, it wasn’t. The depth-sounder shallowed suddenly from ten feet to eight, and then five. I let myself be distracted by some rattle behind me and, as I turned around; the first sickening crunch of rock against boat. I scrambled to get my engines up without tearing off the propellers, but the current had me. C-Sick slammed into barely submerged rocks again and again, making a horrible grinding sound. When the music finally stopped, I was well and truly grounded.

On the bright side, I was unlikely to either sink or drown in less than two feet of water. The bad news was that we were stuck at least fifty river miles from another living soul. My big Arctic expedition ground to a humiliating halt before I even reached salt water.

If there was an instruction book for this sort of mess, I’d never seen it. Improvising, I started offloading sixty gallons’ worth of extra fuel cans into the Zodiac I trailed behind C-Sick. Then I chucked in the heaviest camera and food cases on top. After that, I hopped over the side into the river shallows and began shouldering C-Sick with all my strength. I managed to get her off the rocks and scrambled back on board before she had a chance to drift out of reach. I didn’t have time to celebrate, because she quickly grounded again. The next two hours devolved into a slow-motion nightmare: too many rocks and not nearly enough water. I tasted the rat-breath slick of desperation in my mouth as I struggled to float more than a hundred yards at a go before fetching back up on the rocks.

At one point, having floated C-Sick free, I strung the boat along by a rope tied to her bow, leading her through knee-deep water like a reluctant dog. The sun dropped slowly behind thickly forested hills. It was hours later and nearly dark before I found enough deep water to restart the engines. I painstakingly picked my way into the lee of two small islands and finally dropped anchor with less than ten feet of river beneath me.

At eleven p.m., the last light of day colored high cirrus clouds salmon and blue. This far north, the sky was still too bright for stars. I poured a dram of Irish whiskey to settle my frayed nerves and stepped outside to brave the mosquitoes out on the back deck. I raised a toast to absent friends, thanking them each by name as I pictured their faces, one by one.

I poured the last thimble of my drink onto the river’s swirling surface, a small offering. I hoped it might reach the Bay and mollify its irascible gods. The whiskey was gone in an instant, swept toward the vast sea looming ahead.

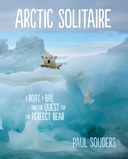

Paul Souders is an award-winning, Seattle-based outdoor photographer whose work has appeared in National Geographic, Geo, Time, and Life magazines, among others. Arctic Solitaire is available in the Seattle Program Center bookstore, on mountaineersbooks.org, and wherever books are sold.

This article originally appeared in our Fall 2018 issue of Mountaineer Magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, click here.

Paul Souders

Paul Souders