I anchored the boat in a bay at the mouth of a pristine coastal stream in Prince William Sound. Leaden clouds covered the valley, masking the serrated, glacier-clad peaks of the coastal range. Under the lichen-draped spruce and hemlock canopy skirting the slopes lay a carpet of moss and thickets of spiny devil’s club, alder, ferns, and blueberry bushes. Rufous hummingbirds flitted through the trees while high overhead, marbled murrelets, a small seabird, nested on the mossy limbs of four-hundred-year-old evergreens, some with a basal diameter of nine feet. Tiny birds atop forest monarchs, a scene as if envisioned by Tolkien.

Ashore, standing on limpet- and barnacle-encrusted cobbles and the shards of countless clamshells, I inhaled the scents of the forest and a vibrant spawning stream. Damp salt air mingled with the smell of dead and dying pink salmon, a rich, pungent aroma more of life than death. Gulls feuded and fussed over fish scraps, their ubiquitous cries filling the air. Two bald eagles perched on the rocks at the stream’s edge, another soared over the tidal flat, scattering the gulls, while just down the bay two juvenile eagles waited high in their enormous nest for a parent to bring food.

The stream seemed so packed with salmon that it looked as if I could have stepped across on their backs.

Mergansers, trailed by their broods, bobbed in the swift current searching for salmon eggs. Small numbers of silver salmon mixed with large schools of pink salmon now forcing their way upstream against the ebbing tide. Just offshore silvers jumped and twisted in the light, eluding harbor seals lurking below.

Every two years pink salmon return to these natal waters to spawn and die. Over the winter, their eggs, nurtured in the gravel by the nutrient-rich, icy water, mature and hatch. The young, called fry, pulse in spring downstream to continue their life cycle far at sea. A magnetic map and chemical clues will guide the mature fish back to this exact spot.

Abundant protein lures meat eaters of all kinds. Twice I had seen coyotes here, once a wolf, and river otters many times. Ravens and crows searched for scraps, stealing from the eagles and gulls alike. At times the stream seemed so packed with salmon that it looked as if I could have stepped across on their backs.

I’ll never forget the first time I came here, by small rented skiff, motoring the calm, gray-green waters of the sound, the distant spouts of humpback whales on the horizon. My companion and I passed a luminous waterfall where a bald eagle perched on a nearby spruce, only the second I’d ever seen. “Look! A bald eagle!” I shouted. My companion scarcely looked. He’d lived here a long time, seen plenty of eagles.

On this day, years later, I came here for the bears. Both black and brown bears lived on this stream and gorged on salmon. A few feet up from the tideline, I saw the first tracks, huge brown bear prints engraved in the sand.

Salmon heads, tails, and bones littered the shore, leftovers of feasting carnivores. When I crossed the shallow stream, hordes of fish panicked and pushed ahead; some flipped right onto the bank. Each sandbar, every patch of mud, was engraved with tracks: gulls, crows, black bears, brown bears. In the upper part of the tidal flat, colored green and gold with moss and seaweed, and near what appeared to be a favored fishing site, I sat down to wait.

Within minutes, a shadow detached from the forest and sauntered into the creek. A brief lunge, a snap of jaws, and like that, the black bear waded out, a pink salmon struggling in its jaws. In a soft, feathery rain, the bear unhurriedly carried its catch into the timber.

Another black bear, smaller and more animated, rushed from the far tree line, ran across the flats, and plunged into the river, salmon escaping in all directions. The young bear charged, left and right, back and forth, pouncing and pawing at every fish but without success. Then, on the bank, it spied a salmon hurtled ashore by the initial panic. The bear charged forward and seized it with its teeth and front paws. Like a robber fleeing a bank, the bear raced off across the flats for the safety of the woods. I was reminded that not all bears are good fishers.

Over the next two hours, I watched the fishing techniques of a half dozen black bears of various sizes and ages. Some wandered in, grabbed a fish, and departed; others plunged in and bucked the current. All of them got fish; a few settled for spawned-out carcasses. Once, near the head of the tidal flat, where the creek emerged from the forest, a female with a small cub made a brief foray from cover but retreated when another bear appeared close by.

An uneasy tension pervaded the glowering mists, and I fidgeted with anticipation. Then, there, across the flats, stalked a giant—a brown bear, one of the undisputed masters of this realm.

Not one single black bear ate its catch on the bank; they all carried their catch into the safety of the woods. It was telling behavior; something dominant and dangerous lurked there.

A lull in the action descended at midday. Hours dragged by without a single bear in view. Eagles wheeled and called; crows yammered from the stream bank; increasing rain beat a steady tattoo. I watched a pair of otters slide over the rocks and panic a shoal of fish. An uneasy tension pervaded the glowering mists, and I fidgeted with anticipation. Then, there, across the flats, stalked a giant—a brown bear, one of the undisputed masters of this realm.

The bear was deep chocolate brown, almost black. No mistaking this hulk for a black bear, for it was at least three times the size of any other bear I had seen that day. The big humped shoulders, the keg-sized head, the long whitish claws identified the species and signified its status: one thousand pounds of fur, muscle, and power. A thought ran through my head: Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil since I’m the biggest, baddest bear in the valley.

The brown bear ambled to the riverbank, scarcely glancing right or left, then wandered upstream, pausing to sniff at scraps and carcasses along the way. He was literally waddling fat, the beneficiary of nature’s munificence. In a pool below a fast riffle that slowed the salmon’s upstream struggle, he waded into massed fish, lowered his head, and in slow motion snapped up a big male pink salmon. He gave the humpbacked fish a slight shake, seemed to study it, and then dropped it back into the water, uninterested. He made another grab and pulled out a fresh, bright female.

Back on the bank the bear used its front paws to pin the salmon to the ground, then ripped the egg sack from the body, sending a scatter of bright red eggs across the rocks. The bear lapped up the nutritious roe, stripped off the skin, then abandoned the rest to the gulls. In early summer it would have eaten the entire fish. Now, having gained tremendous bulk, the bear was picky, stripping the eggs, skin, eyes, and brain, leaving the rest. Others ignored live fish, preferring instead the putrid remains dredged up from the bottom. It was disturbing to watch fish being torn apart, left twitching on the sand, their struggle to spawn ruined, a vivid reminder of the sometimes brutal cycle of life, a macabre dance of predator and prey.

I ended my vigil in late afternoon and walked back to the skiff in pounding rain. Before shoving off, I turned for one last look at the mists drifting across the slopes and over the flats. I listened to the birds and watched salmon forging their way upstream, pleased that this remote stream still supported an abundance and variety of life unmatched elsewhere. All of it harkened to a time when Alaska was wild and pure—solely the kingdom of the great bear, a place where all else gave way to its passage.

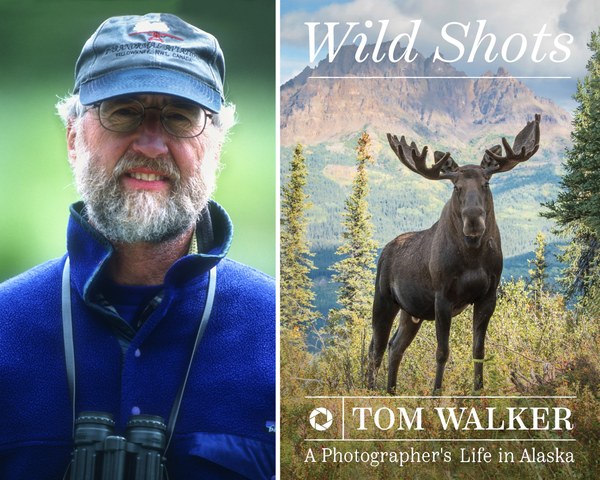

Excerpted from Wild Shots: A Photographer's Life in Alaska by Tom Walker.

Photo at top: A brown bear wades from the rapids, a late-run silver salmon clamped in its jaws. Photo by Tom Walker.

Tom Walker is an award-winning photographer and author of more than a dozen books. Over the course of his fifty years in Alaska, he has worked as a conservation officer, wilderness guide, wildlife technician, log home builder, documentary film adviser, and adjunct professor of journalism and photography.

His latest book Wild Shots turns the lens inward to examine his extraordinary life in the Alaskan wilderness, encompassing striking natural landscapes, adrenaline-inducing wildlife encounters, and breathtaking adventures.

More Books About Alaska

- Alaska Wildlife: Through the Seasons by Tom Walker

- The Seventymile Kid: The Lost Legacy of Harry Karstens and the First Ascent of Mount McKinley by Tom Walker

- The Salmon Way: An Alaska State of Mind by Amy Gulick

- A Wild Promise: Prince William Sound by Debbie Miller

- It Happened Like This: A Life in Alaska by Adrienne Lindholm

- Mudflats and Fishcamps: 800 Miles Around Alaska's Cook Inlet by Erin McKittrick

More Books About Photography

- Arctic Solitaire: A Boat, a Bay, and the Quest for the Perfect Bear by Paul Souders

- Stories Behind the Images: Lessons from a Life in Adventure Photography by Corey Rich

- Photography: Night Sky by Jennifer Wu and James Martin

- Photography: Outdoors by James Martin

- Photography: Birds by Gerrit Vyn (COMING SOON)

Tom Walker

Tom Walker