What is the life of an editor? On television and in movies, it seems pretty glamorous: a posh office, three-martini lunches, perfectly coiffed women leisurely reading through perfectly composed prose. Or there’s the opposite end of the spectrum: cartoon and joke-inspiring lunatics obsessed over grammar and punctuation with pencils in their hair who get all worked up over a misplaced comma.

The reality, at least for me, leans more towards the “lunatic obsessive”. Since I learned what one was a few years ago, I can get pretty fussed about a dangling modifier. But sometimes it’s a book that I go crazy for, in a good way.

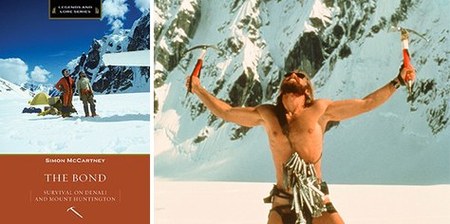

Simon McCartney’s The Bond, the latest installment in the Legends and Lore series, is such a book. We rushed the publication of the book so we’d have copies available in late October, even though it's technically a Spring 2017 book. I’m not alone in my appreciation for the book: it has been shortlisted for the Boardman-Tasker award. But it’s not like it’s the first (or the last) truly excellent book I’ve had the honor to work with at The Mountaineers, so why is this one so important to me?

On one level, The Bond is a very well-told adventure story (or, in truth, three stories); you’ll look a long time before you find a better climbing tale. Young Simon McCartney, of Britain, bumps into ‘stonemaster’ Jack Roberts, of California, in Chamonix in 1977. The two climbers “bond” (get used to it) and hatch a plan to climb the unclimbed north face of Alaska’s Mount Huntington. That goes well, and a year or two later - after Simon has knocked off a winter ascent of the north face of the Eiger - they tackle the unclimbed southwest face of Denali. And it’s here, on Denali, that the true reason for my vociferous championing of this book originates.

Jack and Simon have tied into the rope together, they’ve supported each other, and they’ve suffered together. But it’s high on the dangerous Denali, where Simon falls seriously ill with high altitude cerebral edema (HACE), that the true extent of “the bond” becomes apparent. The two have run out of food and it’s storming. The time has passed for Jack to save himself - not that he’s ever seriously considered it. They need a miracle.

Then it arrives in the form of another pair of climbers. And later other climbers, lower on the mountain, also selflessly abandon their own plans to save the others. None of the players make a fuss about what they’re doing; it’s just what is done. It’s a beautiful and moving story, told with humor and genuine emotion. Just this year that Bob Kandiko and Mike Helms received the David Sowles Award for their actions in aiding Jack and Simon in 1980, but heroes they truly were.

I often admit, sheepishly, that I’m not a climber. In the right company, I’ll follow up by saying that I think those who are might be a bit crazy. But you don’t have to be a climber to be impressed by the friendship and decency that is on show in The Bond. For that, you just have to be human.

Excerpt from The Bond

EXCERPT FROM THE END OF CHAPTER 18

My hand is beginning to freeze, so tightly do I have it jammed in the crack. I am losing sensation and fear I will let go accidentally. My hand is also bleeding from the abrasion of the sharp granite and my blood is acting as a lubricant; unless I solve this next move very soon I will fall and be smashed on the rocks below. I am too far from my last protection now. I must not fall.

The points of my crampons grind and move on the small footholds and my pack pushes me out of the chimney, which is now overhanging. I scream, scream from adrenaline, scream in fear, and scream at the mountain: ‘Let me pass!’

There is a ledge above me. It’s my only hope but I cannot reach it. In desperation I pull my ice axe from the holster on my waist and toss it so I can let go of the head and catch it again at the base of the shaft. With the axe my arm is two feet longer and I reach up with one hooked steel finger towards the ledge.

With a metallic sound I hook the pick over the lip and test the grip. The axe wobbles on its point but does not slip when I pull gently. Time to move. All my options will be over in seconds if I do not.

I pull hard. The crampon on my right foot twists and loses purchase and skates off the rock. Almost all of my weight is hanging off the tenuous grip I have on the shaft of my axe.

I scream. And then nothing.

Am I dead?

Something is holding me tightly, squeezing me with a powerful grip. I open my eyes searching for my captor.

‘Easy, man, you’re OK, it’s OK.’

I seem to know the voice and slowly the veil of confusion subsides as I recognise that it is Jack who grips my arms. My chest is heaving; my pulse is racing. I have awoken from a nightmare but I am not back in Kansas. I have exchanged one bad dream for the same in reality. There is a bloody bandage around my right hand, evidence of my journey.

I sleep fitfully and wake often with a bad headache. It feels like a terrible hangover and I am a little nauseous too. It is the feeling that I had once when I climbed Mont Blanc unacclimatised, so I guess my ailment is altitude-related. I hope I get over it: we have a long way to go and we have still not reached the halfway point of the technical section, or the crux where the big boulder is.

That overhanging chimney could have been the end of me. I nearly fell twice today. This is insanity. I never allow myself to get out of control like that, but what choice do we have? It is too late now: we cannot get down and if we cannot climb the rock band we are dead men.

Mary Metz

Mary Metz