In June, Braided River launched Big River: Resilience and Renewal in the Columbia Basin - a stunning photography book and engagement campaign spotlighting the Columbia River watershed. The Pacific Northwest’s largest river system - called the Big River by many Indigenous nations of the West - covers a landscape the size of France, beginning in the Canadian Rocky Mountains and ending at the ocean mouth, near Astoria, Oregon.

David Moskowitz is a photographer and storyteller committed to telling complex stories about our region’s lands and waters and the relationships between settlers and the First Peoples of these lands. To take these photos, David climbed mountains and backcountry skied. He waded through streambeds and sat quietly while salmon swim upstream to spawn. His photographs are a testament to witnessing the land, water, wildlife, and human communities as one great being, spanning nations and states.

In this excerpt from his new book, David explores the many names of the Columbia, their various meanings, and how to make sense of its rich, complicated story.

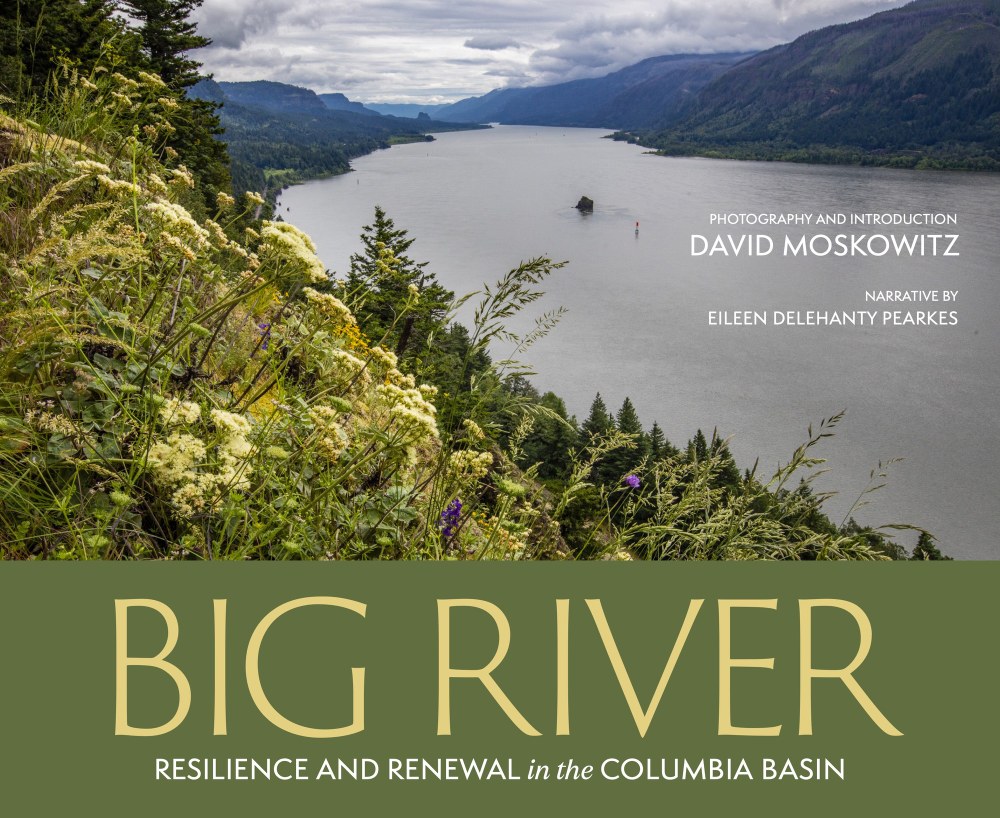

The Big River flows freely through the Columbia River Gorge toward the Pacific Ocean. Photo By David Moskowitz.

Bringing the Big River into Focus

By David Moskowitz

Day and night, the Big River - also known as the Columbia River - shoots an enormous volume of water out of the west coast of the North American continent, a freshwater arrow running headlong into the swelling Pacific Ocean. There, it is swept up and carried back inland to begin again as rain and snow, setting the stage on which the plants, wildlife, and humans build their lives in this watershed. Where precisely does the story of this magical river begin?

In reality, the start of any river, especially one as sprawling and complex as the Big River, can be defined in numerous ways. Wherever moisture falls upon the land is a starting point, each with its own unique contribution to one of the most ecologically diverse regions of North America. No matter where you begin, it’s an awesome journey. The river touches the lives of millions of people, both within and far beyond the boundaries of the watershed, sometimes in ways we know and love and at other times are completely oblivious to.

This vast richness and diversity has defined my own journey to explore and document the watershed. Over the course of capturing photographs for this book, I have found myself taking pictures of desert wildlife one day, dam operators navigating huge barges down the Snake River the next, and people fishing for salmon on a rainforest-shrouded tributary the next. Two days after eating lunch on the banks of a river that begins in the arid mountains of central Idaho, I was trekking across ancient ice atop some of the highest peaks of Canada. Driven by logistics, my schedule for this project was exhausting at times but in retrospect also reflected perfectly the task at hand - how to create, in a collection of images, a snapshot of a place of infinite complexity at a finite and singular moment in time.

The idea of a river may conjure an image of a fairly predictable linear flow of water down an existing course. A river’s watershed, however, is another thing entirely. It encompasses myriad hydrological, ecological, geological, and cultural processes, activities, and characters, all going about their business simultaneously in frenetic spasms of interaction. The ecological, cultural, and economic value of the Big River’s watershed is immense. The wrangling over who benefits from, controls, or gets access to this value has been going on for centuries. In our generation, however, we are reaching a new inflection point as the dominant settler-colonial culture comes to terms with the existing unsustainable nature of their relationship with the watershed while Indigenous nations rebound and renew their efforts to steward their territories.

The 550-foot-tall (168- meter) Grand Coulee Dam in Washington State is a mile (1.6 kilometers) wide and backs up the river for 152 miles (245 kilometers). In 1942, it extirpated anadromous salmon from hundreds of miles of spawning habitat in the upper Columbia River watershed. Photo by David Moskowitz.

Over time, this river has been graced with many names. Indeed, given that dozens of Indigenous languages and dialects are spoken within the boundaries of the river’s watershed, this should not be surprising. Many of the Indigenous names for parts of the river reflect the character of a specific section of the river included within the territory of a particular group.

The Sinixt speak nslxcin, or “people’s speech,” an Interior Salish language of several distinct tribes who traditionally inhabited the Columbia, Okanagan, SanPoil, Pend d’Oreille, and Methow River basins. They refer to an important place on the river where they gathered to fish as Sxwnitkw, which translates to “roaring or noisy waters,” a place known colonially as Kettle Falls. Probably the most ubiquitous name used by Indigenous people in reference to the entire river translates to “Big River.” Interacting with Indigenous people fishing along the river today, you often hear the river referred to as either just “the River” or “the Big River.” In my own quest to understand this river, it was the name “Big River” that captured the magnitude and importance of this river system and all contained within it.

Out of respect, canoes are lifted and carried on shore rather than dragged. The Sinixt people are bringing this canoe ashore for a salmon-honoring ceremony at Sxwnitkw, which translates to “noisy fast water,” a reference to the rapids here before the river was flooded by the construction of the Grand Coulee Dam. Carved into the canoe are representations of ancient rock art from various places in Sinixt traditional territory. Photo by David Moskowitz.

The name “Columbia River” deserves some attention here as well, of course. That this is the only name the majority of non-Indigenous peoples in the watershed - and almost all peoples from beyond the watershed’s boundaries - will recognize today speaks to a central theme of the river’s contemporary cultural story. This is the overwhelming impacts of settler colonialism on both the watershed directly and our cultural perspective on the river. As with all things “Columbia” in North America, this name for the river traces back eventually to Christopher Columbus. Unlike Indigenous names for the river, this name reflects nothing about the actual river system. It harkens back to a colonial society’s founding myths - the doctrine of discovery and manifest destiny among them - racist and destructive today as they have been for centuries. The continued persecution of ecological and cultural diversity across the watershed speaks to the power these stories continue to wield. Each time we say the name of this river, we choose which stories we feed and which we starve.

To read the rest of this essay, you can buy the book at bigrivercolumbia.org.

Sunset over the confluence of the Twisp and Methow Rivers. Photo by David Moskowitz.

Ways to Connect with Big River: Resilience and Renewal in the Columbia Basin

July was a big month for the Columbia River. On July 11, the U.S. and Canada reached a tentative "agreement-in-principle" on the renegotiation of the Columbia River Treaty - an update to the treaty that has managed the Columbia Basin and its hydropower dams for more than 50 years. Decisions like these define our region for generations, from energy development to food production and outdoor recreation opportunities, and we all have a stake in what happens next.

We expect that soon there will be opportunities for the public to provide input on this issue. Sign up for Braided River’s mailing list to hear about future engagement opportunities around the Columbia River Treaty. In the meantime, I invite you to read this in-depth piece about the Columbia River Treaty recently published in the Seattle Times by Lynda V. Mapes.

The Columbia River changes everything it touches, including us, and our community’s collective choices about the river are in our hands. Here's a few other ways you can join the Big River conversation.

- Buy a copy of Big River from Mountaineers Books, your local bookstore (including the Seattle Program Center Bookstore) or one of these online sellers.

- Attend a book launch event. The Big River book tour is traveling the West. Find an event near you, or join a virtual event.

- Explore the Big River website and follow the journey on Braided River’s Instagram.

- Follow our Braided River's partners, Save Our wild Salmon, who advocate for healthy salmon habitat and Indigenous solidarity in the Columbia Basin.

Big River: Resilience & Renewal in the Columbia Basin is available wherever books are sold. Get your copy from Mountaineers Books, and learn more about the campaign at bigrivercolumbia.org.

Erika Lundahl

Erika Lundahl