Birds accompany us daily in our neighborhoods with their songs, bright colors, and energetic activity. We seek them out, from urban wetlands to wilderness trails, following the sound of a distant twitter or song. In Birds of the West: An Artist's Guide, award-winning artist Molly Hashimoto captures the likeness of nearly 100 species using different media.

In the following excerpt from Birds of the West, Molly shares her thoughts on wetlands and the birds found there, along with several pieces of her stunning art.

Wetlands & Ponds

Where I live in Seattle near Lake Washington, there are two wetlands within walking distance, near the University of Washington: Union Bay Natural Area and Magnuson Park. Around Puget Sound, there are also saline wetlands and estuaries that include marshes and tidelands with eelgrass beds, as well as countless freshwater wetlands. Many of the birds that have inspired my art were first observed in wetlands, both near my home and farther afield. Waterfowl don’t hide in trees, as many other avian species do, so they’re easy to see, and many of them are with us year-round. Best of all, waterbirds have the most color and dramatic markings.

At Union Bay Natural Area, just north of Seattle’s Husky Stadium, you might observe wood duck pairs paddling in harmony, the drakes gloriously attired in ruby, emerald, and sapphire hues. Trumpeter swans sparkle in the wider spaces of the bay on a sunny February day. Great blue herons, pied-billed grebes, and northern shovelers are ever present in winter, adding movement to the quiet world of the reclaimed wetland. In March, red-winged blackbirds trill out the earliest notes of springtime; a ring-necked duck punctuates the pale water with its dark head. Later in the year you might see a green heron if you’re lucky, or a Wilson’s snipe.

If you travel far enough north in the state, you’ll see loons nesting and fledging on lakes in summer. One evening I saw a pair swimming in Diablo Lake in North Cascades National Park, and though I’ve only seen them once, I’ve heard them several times on early summer mornings there. In wetlands far to the east, sandhill cranes gather in spring at Blacktail Ponds in Yellowstone National Park, preening in the thawing sloughs. Clark’s grebes perform their exquisite courtship dance on Lower Klamath Lake in Northern California, while white-faced ibises there decorate the marshes with their exotic flamingo shapes and iridescent copper and verdigris plumage.

Such places, along with Washington deltas including the Nisqually, Stillaguamish, Nooksack, and Skagit, create major habitat for waterfowl. In his book Against the Grain, James C. Scott writes about the importance of wetlands to birds, particularly migratory ones: “ . . . the most common route for a great many of these migrations has been via the wetlands, estuaries, and river valleys of major waterways, owing to the density of nutritional resources they offer. Bird migration routes favor marshes and river valleys, as do, more obviously, the movement of anadromous salmon . . . Any watercourse is itself a nutrient trough with its own flood plains, back swamps, and alluvial fans.”

Watercourses are a habitat requirement for us humans as well. Throughout history most of our larger population centers were founded on estuaries, river hubs, and waterways. We feel most at home in these places, where there is adequate food and water for us and a diverse web of plant, bird, and mammal life that also supplies endless subjects for our imaginative life. In this way, the rhythms of nature continue to govern us.

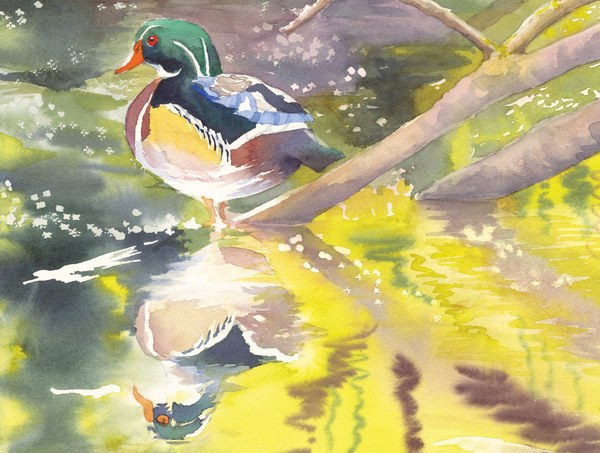

Wood duck (Aix sponsa)

The opulently colored male wood duck I painted in the watercolor nests with his mate just behind the University of Washington’s Husky Stadium, a surprisingly quiet little backwater of Union Bay. I’ve seen them there in winter many years. My artist eyes are drawn to the iridescent green feathers and white markings that set off the maroon breast so dramatically. The male wood duck is perhaps the most beautiful of North American waterfowl. The courting male wood duck swims before a female with wings and tail elevated and tilts the head backward for a few seconds. At times the males may also drink, preen, and shake in a ritual fashion. The block print (top) celebrates a drake that I saw swimming on an autumn day when the cottonwoods and maples on the east side of the Cascades were at the peak of their golden color display.

Common loon (Gavia immer)

Wildlife abounds in North Cascades National Park, but loons are rare. One summer evening when I was teaching a watercolor workshop for the North Cascades Institute, my students and I were graced by this pair swimming in Diablo Lake on the brink of Diablo Dam. The patterns of the loon plumage beside the choppy water (winds pick up there as the day wears on) created an indelible image, which I photographed, in order to paint later. The color of Diablo Lake becomes nearly turquoise in later summer, when the glaciers high above begin to thaw. Earlier in the season the water is mostly snowmelt, which shows up in the lake as a clearer greenish color. By August, the rock flour in the glacial melt appears in the lake so that the water hue becomes a more opaque teal color. People have questioned me about the color in my North Cascades lake paintings, thinking that I make it up, but I assure them the color is really just like that in late summer.

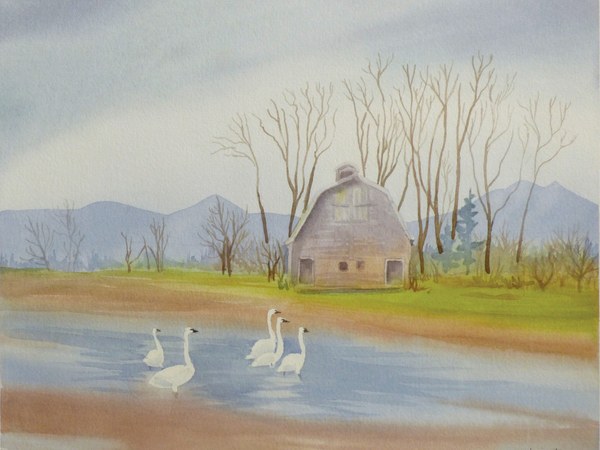

Trumpeter swan (Cygnus buccinator)

The trumpeter swan is the largest waterfowl in North America, standing on average four feet tall, with a wingspan of seven feet. Trumpeters breed in Alaska, and a large contingent of one of North America’s three populations, the Pacific Coast swans, winters in Washington’s Skagit Valley. According to Martha Jordan of the Northwest Swan Conservation Association, only fifteen trumpeters were reported in Skagit County in the early 1960s due to widespread hunting that nearly wiped them out. Since that time, hunting trumpeters has been prohibited nationally, and the trumpeter is one of conservation’s greatest success stories: 11,000 were counted in the Skagit Valley in January 2017. One major task left in protecting this magnificent species is the cleanup of agricultural fields and ponds that still contain residue of the lead shot used for hunting ducks and other species. An effort is being made to identify and remove the toxic shot in those areas.

The white of a swan in winter is one of the purest colors you’ll ever see, inviting endless artistic interpretations. With the watercolor, I attempted to capture the low light and soft grays of winter in the Skagit Valley of Washington; with the woodblock, the stunning contrast of the swans’ white bodies with the water surrounding them.

Molly's book Birds of the West explores six other Western habitats through more than 130 sketches, paintings, and prints. Meet Molly at one of several upcoming events, or connect with her online at www.mollyhashimoto.com.

Mountaineers Books

Mountaineers Books