by Steve Scher

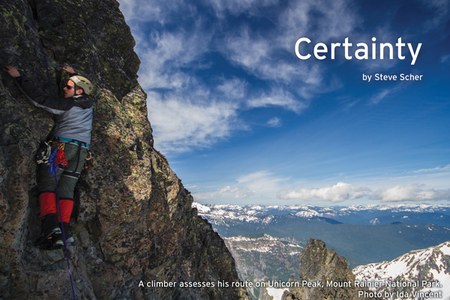

A climber, staring up from below, already has the summit in mind. The cracks and crevices might be as thick as an interstate on a highway map or as faint as a Jeep trail. The route will emerge.

Training, strength, conditioning, practice — these are the reliable vehicles a smart athlete commandeers to make it to the top.

Certainty powers the journey. This is the certainty that comes from inside, where she has tested and retested herself until she knows her skills and her limits.

Because outside, beyond the training and the practice, out in the world where wind can howl and snow can blow, there is no certainty.

Rock is deceptive. Andesite cracks. Granite chips. Schist splits.

Glaciers shift. Crevasses widen. Trails vanish.

A stumble here. A misstep there. You never know. The very earth can grind against itself and slough off clinging souls like so much dry skin.

In language, you might read that the opposite of certainty is doubt. Doubt will hold you at base camp. Doubt could undermine all that work you’ve done to get to the starting point. Because you could think that doubt means that there is certainty to be had all around you, but you don’t have it.

Philosophers of all stripes have been grappling with certainty for centuries, and all temper certainty with doubt.

Bertrand Russell, “In all affairs it’s a healthy thing now and then to hang a question mark on the things you have long taken for granted.” Benjamin Franklin, of course, opined, “in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” Franklin is right about the first, but more than a few have managed to avoid the second. But leave that.

The early 20th century logician Ludwig Wittgenstein has written a whole book, “On Certainty.” He is most stressed by the notion. He wonders if holding the certain idea that unicorns do not exist calls into question the existence of, say, armchairs as well.

Wittgenstein himself turns inward at the end. “I act with complete certainty, but this certainty is my own.”

On a mountain, backed by training, testing and the understanding of our own limits, that kind of certainty can be a guide.

Without something beyond intuition and feelings to go on, who is to be trusted beyond yourself. Woe be to an acolyte of a rigidly certain leader. The followers of Mao and Stalin can attest to that.

Einstein believed in intuition and inspiration. He may have felt he was right, he has written, but he didn’t know it. For that, he turned to science. And science is full of uncertainty and doubt.

The problem today is that the certain people aren’t thinking scientifically. A hundred and sixty years ago Charles Darwin had the same problem.

“Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge.”

Where the sword has given way to the power of the purse and the law, those enamored of their certainties call down an avalanche of punishments.

Better that certainties and doubts walk hand in hand. Tony Schwartz, the journalist and author says it well. “Let go of certainty. The opposite isn’t uncertainty. It’s openness, curiosity and a willingness to embrace paradox, rather than choose up sides.”

Now, that kind of thinking won’t convince the zealots, but it will get you to the summit. If you’ve trained for it.

This article originally appeared in our July/August 2015 issue of Mountaineer magazine. To view the printed article and read more stories from our bi-monthly publication, click here.

Steven Scher

Steven Scher