My first fall is a well-mitigated disaster. Alvero performs his part flawlessly — the disaster is all mine. With my feet at about the height of a bolt and my knees bent, I cling to an awkwardly located crimp at my left shoulder and a side pull to my right, while twenty feet below me, Alvero explains to the group what he is going to do as I fall.

When he tells me to let go, I am more than ready. Or so I think. Instead of pushing off the rock to fall in a graceful arc and land with my feet into the wall as I should, I just let go and slide straight down the face. My feet shoot up over my head and I come to rest, dangling upside down with my back against the wall, uninjured and undignified.

This is how I spend my second day leading an Alpine Ambassador-Hosted Cragging Trip in El Potrero Chico, Mexico.

Scott on selam, lower virgin canyon. Photo by brian degenhardt.

Scott on selam, lower virgin canyon. Photo by brian degenhardt.

El Potrero Chico

“El Potrero Chico” means The Little Corral. It is neither little nor a corral, but it is smaller than its big brother, Potrero Grande, located a few miles across the valley. The park is managed by the state of Nuevo León, and is part of the Sierra del Fraile, a national protected area that includes a much larger territory spanning six municipalities. Home to a gigantic run-down water park (which, they tell me, is still open in the summer) and an abandoned mine that used to supply limestone to the local cement plant, El Potrero Chico’s towering rock walls form a kind of natural corral, encircling an area of almost 30 square kilometers. The 2,000-foot limestone stockade attracts the attention of most visitors.

On the weekends, families drive out from the nearby metropolis of Monterrey to stake out shady picnic shelters, their red painted roofs riddled with holes from rockfall. Children run back and forth tossing pebbles while their parents turn up cold drinks and watch crazy gringos scale lines of bolts up the massive walls.

We’re not all gringos, of course. Climbers come to this internationally-renowned climbing destination from all over the world (not just North America). I meet people from Chile, Spain, the UK, and Canada during the week I spend here. This is my second visit to the park since “discovering” the place for myself in 2022.

Potrero, as its commonly known, was discovered by Mexican climbers in the 1970s, before the popularization of modern climbing gear. At that time, rock climbing was a wild and hazardous affair not for the faint of heart. Still, Mexican first ascensionists climbed bold 700-meter lines on El Toro with very little protection and left behind even less in the way of artifacts or records of their passage. In the mid 1980s, a contingent of climbers from Austin, Texas, including the prolific route developer Jeff Jackson, moved into the area. They befriended Homero Gutierrez Villarreal, a local landowner, and launched a campaign of cleaning and bolting that spanned two decades and gave rise to the bedazzled Potrero Chico of today.

Climber's Mural at Finca El Caminante. Photo by Dean Hunter.

Climber's Mural at Finca El Caminante. Photo by Dean Hunter.

A Mountaineers contingent

Our group is eleven climbers in total, representing five branches of The Mountaineers. I’ve arranged for us to stay at the Rancho El Sendero, a yellow stucco motel and campground walking distance from the park. It has a beautiful campus dotted with orange trees, a swimming pool, and an epic view of the mountains. Seven of us share a no-nonsense bunkroom. The others opt for more private (though equally spartan) habitations at the other end of the building. By the end of the week, I am grateful that we’ve spread out and are therefore spared a bit of each other’s filth.

I’ve been a Climb Leader with The Mountaineers for about six years, but I still have anxiety about planning and leading a trip in Mexico. In 2016, I went on a stressful, somewhat disappointing mountaineering trip to Switzerland with two acquaintances. The combination of technical mountaineering, international travel, and personality issues proved too arduous for some relationships to bear.

The Canyon at El Potrero Chico. Photo by Brian Degenhardt.

The Canyon at El Potrero Chico. Photo by Brian Degenhardt.

Potrero is not the Swiss Alps, however; and sport climbing is, well, sport climbing. There are objective hazards to be sure, like rockfall, rattlesnakes, and sun exposure, but following a line of 3/8” bolts with shiny silver hangers is relatively simple in comparison.

Warming up on the first day, we follow those bolt lines without problems, anchors glinting like diamonds on a necklace hung from the ridgetop. As we climb pitch after pitch of sublime, secure rock under the Mexican sun, my worries about scorpion dens and disintegrating rappel anchors tumble away.

Our trip is sponsored by the Alpine Ambassadors Committee to reward a handful of our many deserving climbing instructors and super volunteers, auspiciously with a subsidized trip to escape the blue-gray winter of the Pacific Northwest. (We’re not all skiers!) Our expressed purpose is to get people climbing hard multipitch routes outdoors in the off-season. But hard is a relative term, of course, and what makes a climb hard can be more than its physicality.

I’ll make an observation here that may not be that insightful or interesting, but maybe it will pull back the curtain on what seems like a stoic and reckless hobby: the truth is that climbing is often scary, even for climbers. I don’t usually call out the obvious (or what seems obvious to me), but it’s worth doing in this case because in climbing we subconsciously minimize our fears (when we’re not actively stomping them down). Fear is at the heart of what makes climbing hard and is a big part of what makes it thrilling.

Fear also holds us back.

Dean Hunter relaxing at the top of Will the Wolf Survive.

Dean Hunter relaxing at the top of Will the Wolf Survive.

Photo by Sergey Frolov.

Learning to fall

And so, on our second day, we meet Alvero Peiro at a cliff called Cat Wall. He’s a guide from Spain who has come to lead us in some exposure therapy for falling. Because fear and excitement are closely intertwined in the brain and body (their physiologic states are so similar), the distinction between mortal danger and a good time becomes more like a matter of opinion than an objective truth. A quickening pulse, faster breathing, shifting blood volume, and intense mental focus crossing into tunnel vision — these have all evolved because they helped our predecessors get out of tight spots. Since my body can’t always tell the difference between fear and fun, I hope that some controlled falls with Alvero might teach me the mental gymnastics to convert the startled horror of falling into a milder fear, or even a cheap thrill.

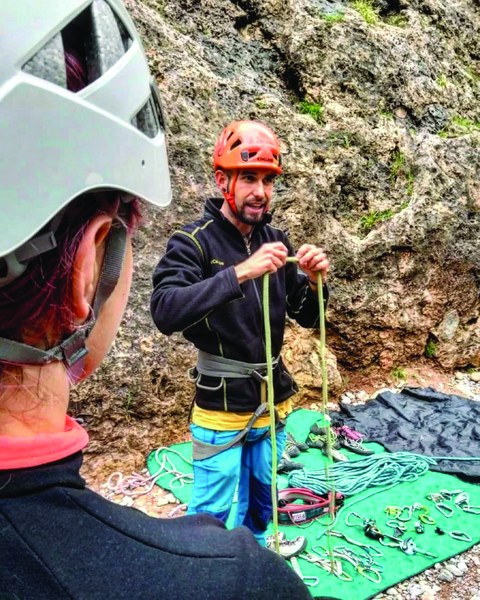

Alvero Peiro raining knowledge on some clients. Photo courtesy of Alvero Peiro.

Alvero Peiro raining knowledge on some clients. Photo courtesy of Alvero Peiro.

Alvero starts with a review of belay technique; I am slightly bored, but not surprised. As the person who catches the falling climber, the belayer is the foundation of the rope safety system and learning to belay is the first thing a new rock climber must master. I am expecting this lesson, especially because Alvero is a guide unfamiliar with our abilities and he can’t take us at our word. He needs to see that we are all belaying safely: that we rig the device correctly, we’re managing the rope, controlling the break strand, and that we’re paying attention to the climber.

I try to relax and let him give the obligatory belay lecture, but after five minutes I feel awkward and am concerned he is losing the group. I have a lot of respect for guides and the experience they bring, so rather than interrupt or insist that our group is more advanced, I try to help things along by agreeing and adding a few comments about how we teach fundamentals to our students. When he asks for a volunteer to climb so he can demonstrate catching, I throw a hand up. My other hand is already pulling on my shoes. I am anxious to move on.

And this is how I find myself humbled on the wall as I hang upside down above Alvero and a dozen eyeballs. Sarcastic climbers may tell you that it doesn’t hurt to fall… it’s hitting the ground you should be afraid of. Flippant and not entirely accurate, the comment does contain a grain of truth.

Audrey Gleser trying hard. Photo by Brian Degenhardt.

Audrey Gleser trying hard. Photo by Brian Degenhardt.

The art of the catch

Thankfully, over the course of the day, I get better at falling. By the end, I’ve taken a couple of four-meter falls and stuck the landings. It works to diminish my fear of falling, but the more valuable take-away turns out to be Alvero’s lesson on the subtle and under-appreciated art of the catch. We learn to be attentive and dynamic belayers, constantly managing the slack based on where the climber will land to put them in the safest place at the end of the ride. All the time he’d spent this morning talking about belaying was an investment in this result. Knowing that your belayer has learned the subtle art of the catch can be a calming tonic when you feel miles above your last piece and you’re pushing hard against your psychological boundaries.

By midweek, we find our routine. We wake shortly after sunrise to have breakfast in the communal kitchen — usually something in tortillas, like eggs scrambled with chorizo or vegetables, along with coffee, papaya, and avocado (always, everything with avocado). We chat about where each of us wants to climb, then the group disbands.

We climb in small groups until sundown every night, sometimes longer. A pair of powerful lamps splash light across the face of Wonder Wall until 10 or 11 at night so that we can climb without headlamps, but we usually wrap up at dark. Then we follow our noses, staggering into whichever food stand entices us. But by the end of the week, we’ve all agreed on which puesto has the best food and there is no need to coordinate our meetup location over the radio. The first group out just announces, “We’re down, we have a table,” because everyone knows we’re meeting at Crux.

Nine of our eleven at Crux. Photo courtesy of scott braswell.

Nine of our eleven at Crux. Photo courtesy of scott braswell.

On the last climbing day of the trip, we join the Yosemite Facelift Service Project. They have selected El Potrero Chico as their first international crag clean-up, and boy is it needed! The park is “well-loved” (i.e. abused) by many. Locals leave their picnic trash and beer bottles; climbers poop everywhere; wind plucks the trash out of the open 50-gallon drums and scatters it across the landscape. The spiny flora snags it, and the refuse spends the rest of eternity skewered like frog parts in the biology lab, a grotesque eyesore.

They give us mechanical grabbers and vinyl gloves, but most of the trash has been sterilized a thousand times over by the sun’s intense UV rays, so I don’t bother with either. The larger items like Styrofoam takeout trays and empty six packs are collected quickly. The rest of the morning, we are on our knees in the dry riverbed picking shards of glass and disintegrated bits of straws from the gravel. I am surprised at how satisfying it feels to unearth an intact bottle label with all the glass fragments still attached.

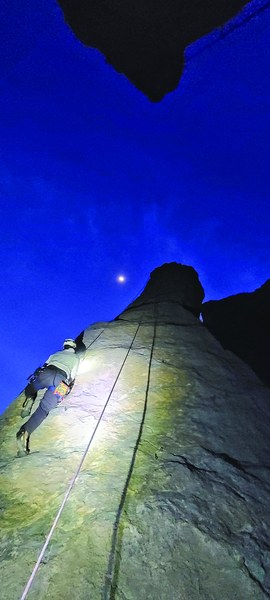

Steve McCarthy on Chico Spire by moonlight. Photo by Sergey Frolov.

Steve McCarthy on Chico Spire by moonlight. Photo by Sergey Frolov.

The wind is howling as we climb The Spires by moonlight on our last night. I smile to myself knowing that all the trash barrels below are empty. It’s been an exhausting, memorable, and at times magical trip. None of the worries or self-doubts that had nagged me during the weeks of organizing seemed to materialize. I planned and prepared enough. My Spanish was sufficient. We faced unpredictable complications, but no accidents. The two bags of first aid supplies I brought were barely touched all week. Nobody bickered, complained, or asked for more than I could accommodate. I leave Potrero wondering what I had been so afraid of.

On our final walk out of the park, we see the first and only scorpion of the trip, skittering alongside the road, crisscrossing through the rays of our headlamps. We take a photo for the group album and then leave it in the dark. He and I can face-off another day.

This article originally appeared in our fall 2023 issue of Mountaineer magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, visit our magazine archive.

Scott Braswell

Scott Braswell