The alarm jolts us from our slumber at 4:45am. I unzip the tent and walk to the cliff to see a blue sky on this clear, April morning. I feel no wind. A happy scream escapes me as I run back to camp. With no time to lose, Ricardo and I stuff cereal into our mouths while dressing in our paddling clothes and drysuits. Coffee will need to wait. We have to start paddling quickly, before the wind returns.

We are two weeks into crossing Alaska by human power, from Ketchikan at the southern tip to Kotzebue in the far north. At more than 3,000 miles, our route travels through Alaska’s most remote areas. We set aside six months to paddle the Inside Passage with our packrafts, hike along the Lost Coast, cross the Wrangels and Alaska Ranges, bike up to and hike across the Brooks Range, and paddle the Noatak River until Kotzebue. The trip is self-supported, with planned stops in town every 14 days or so to pick up packages of food shipped from Seattle.

Our route across Alaska.

Our route across Alaska.

Upon leaving Ketchikan, we quickly learn that good weather in the Inside Passage often brings northerly headwinds. Our transportable packrafts offer the flexibility to walk on beaches when the weather is too rough to paddle, but they have one major drawback: they’re impossible to paddle against wind. We have to get out ahead of the wind we know is coming.

Difficult start in the Inside Passage

We left Petersburg five days ago in heavy rain. We were elated when the weather switched to sunshine, only to be flattened quickly by the wind. Yesterday, as we rounded Cape Fanshaw, the full brunt of gale blew us backward. With no beach to walk on for the next 30 miles, we had no choice but to pull our boats to shore and wait for the wind to stop.

This unplanned camp isn’t the first time since leaving Ketchikan that the future of our adventure is at risk. On only our fifth day, a late winter storm froze the ocean water in the bay along our route, forcing us to turn back to Ketchikan. We could take one big setback, but a second one?

Enjoying great hiking and incredible views of Mt. Hayes in the Alaska Range.

Enjoying great hiking and incredible views of Mt. Hayes in the Alaska Range.

Exploring an ice tunnel of the Chistochina Glacier, formed by a meltstream.

Exploring an ice tunnel of the Chistochina Glacier, formed by a meltstream.

But this morning at least, luck is on our side. We paddle furiously toward the uninhabited Five Finger Lighthouse, perched on a tiny rocky outcropping in the middle of the sound. We climb up the rocks covered in anemones, chitons, sea stars, and urchins, careful not to poke a hole in our packrafts. We have the island and lighthouse to ourselves and the freedom and protection to wait here for the next wind-free day.

Two days pass. We watch orcas swimming, humpback whales breaching, and sea lions and dall porpoises fishing. While unplanned, the wind has given us a gift: the time to enjoy a piece of paradise. It’s also taught us to be patient and believe in ourselves. We choose to listen to what nature is saying. In two weeks, we’ll reach the end of the Inside Passage, completing the first part of our long journey through Alaska.

Suffering on the Lost Coast

Thorns of salmonberry bush dig into the skin of our hands in early May. We will remove thorns from our hands for the next two weeks, but right now we don’t even notice. All we can think about is if the bushes will hold our weight. Below, a steep chute of loose boulders drops straight into the ocean. A fall now will mean grave injury.

We’re in Boussole Bay, the last bay before the Lost Coast, and we can’t find the bear trail we’re supposed to follow. Slowly, Ricardo takes another step toward a grassy knoll and pulls himself up to safety. I follow. We are out of harm's way, but shaken and exhausted. We set up our tent on a tiny ledge, more of a hole than a camping spot, with only half a liter of water left between us. We eat dried apples and crackers with butter, augmented by small sips of water.

Soaking up a moment of sunshine after a long day scrambling in the rain through endless boulder fields toward Kaluluktok Creek in the Brooks Range.

Soaking up a moment of sunshine after a long day scrambling in the rain through endless boulder fields toward Kaluluktok Creek in the Brooks Range.

We wake in the middle of the night to the sound of rain pattering on our tent, a godsend. We collect it with our pot to quench our thirst. Alaska has a way of humbling you, but tonight Alaska is also taking care of us. In the morning, we will spend countless hours climbing up and down three ravines, still unable to find our way out of the bay’s maze. We will despair, going to bed with tears streaming down our faces. But tonight, we drink in our appreciation of Alaska.

On the third morning in Boussole Bay, we wake to a glassy ocean, a rare break. Usually this coast is so rough that paddling our small packrafts isn’t an option, but the Lost Coast seems to beckon. Surprised by our luck, we paddle around the headlands and start hiking the 400-mile long beach.

Hiking is our preferred mode of travel, but our confidence is shaken from our struggles in the maze. And, it seems the Lost Coast is no longer welcoming us. As soon as we start hiking, rain sets in and doesn’t stop for 12 days. Temperatures hover barely above freezing and we have zero views of the impressive St. Elias Mountains. Many close encounters with the omnipresent, gigantic brown bears wear us down a bit more each day, and our determination withers. Then we begin to feel guilty. We have chosen to do this trip and feel pressure to enjoy it. But right now, there’s not much to enjoy.

When we finally reach Yakutat, we barely recognize ourselves in the mirror. We’ve lost weight and our faces look hollow. We’re defeated, but we’ve dreamed of this adventure for so long and we can’t stop now.

Full of dread, we leave Yakutat for the second half of the Lost Coast. A gorgeous evening across Yukatat Bay, complete with stunning views of Hubbard Glacier, lifts our spirits. Then the rain returns. Four days later, Ricardo sprains his ankle.

Despite his pain, we continue for three days until we reach Icy Bay, roughly the 700-mile mark of the trip. We know this is one of the hardest bays to cross. Our weather forecast warns of a big 7-day storm, and we know it is simply too dangerous to paddle. The storm forces us to do what we should have done earlier: fly to Seattle to take a much-needed break. We have pushed ourselves too far.

Jumping over meltwater pooling on aufeis (overflow ice) in late June on Anaktuvuk River in the Brooks Range.

Jumping over meltwater pooling on aufeis (overflow ice) in late June on Anaktuvuk River in the Brooks Range.

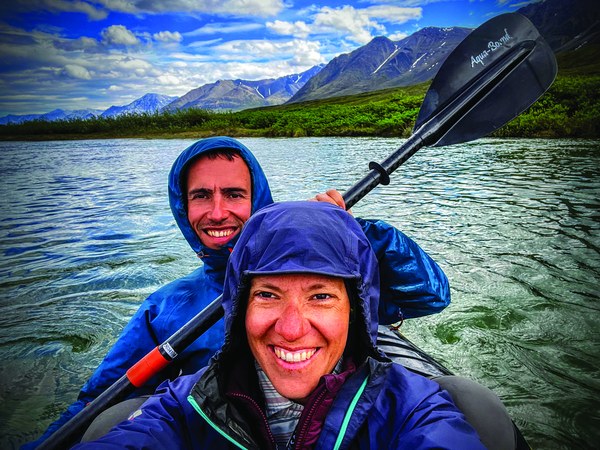

Floating down the John River in the Brooks Range crammed into a single packraft.

Second chance

While Ricardo’s ankle heals, we brainstorm how to best use our remaining four months off from work. We decide to shorten our route, leave the Brooks Range for another time, and reverse our itinerary, setting off from Healy, near Denali National Park, in early July to reach Icy Bay before fall.

Back in Alaska, Healy greets us with blue skies, sunshine, warmer temperatures, and fewer mosquitoes than usual for this time of year. Our packs are lighter too: this time we are only carrying a single, one-person packraft for us both. We hike east, parallel to the Alaska Range, crossing valleys and glaciers and admiring the stunning mountain range with glacier-capped peaks. Wildflowers are plentiful, and to our surprise we don’t see anyone. We finally feel in our element.

After ten days of hiking, we arrive at the shore of Delta River, the last obstacle before reaching a highway that will bring us into Delta Junction. With only one packraft, we’ve developed a technique of crossing rivers by ferrying three times to the other shore: once with each backpack and a final trip with both of us in the boat. But this crossing is different. The current is too strong and the river too wide to ferry multiple times.

We load our gear inside the packraft’s tubes and cram into the boat. We’ve heard many accounts of people capsizing, even with a packraft each. Our safety plan consists of stuffing a satellite messenger, lighters, and energy bars into our pockets while wearing rain gear - not very comforting. Once on the water, we realize that the boat is hard to steer. Sitting at the front, I point out rapids and shallows that Ricardo can hardly see while paddling at the back. Stroke by agonizing stroke, we maneuver safely to the other shore.

We spend the next three weeks in the Alaska and Wrangels Ranges enjoying gorgeous scenery, steady progress, and wildlife. We see caribou, dall sheep, coyotes, foxes, lynx, wolves, and bears. Our smell and hearing sharpens and we develop a sixth sense for bears, often feeling their presence before we even see or hear them. We learn to trust this sense.

Biking to the Brooks Range with the Alaska Range in the background.

Biking to the Brooks Range with the Alaska Range in the background.

Taking in the view of the Chistochina Glacier in the Alaska Range.

Taking in the view of the Chistochina Glacier in the Alaska Range.

One evening, we pass a little meadow perfect for camping, but something in our intuition tells us not to stop. We inch closer to check and sure enough, a black bear – not more than five yards away – runs out of the brush. We continue down the river for another hour to get away from the bear, feeling uneasy without understanding why. Nearly 20 bald eagles surround us as we set up camp. The next morning, the reason for our unease becomes clear: the river we’d been hiking along is filled with spawning sockeye salmon, a perfect meal for a bear.

For the rest of our time in the Wrangles, we hike on faint historical trails through settlements from the Gold Rush era leading to McCarthy, where we pick up the second packraft. As we paddle down the Copper River to the ocean, we’re surprised to fall in love with the very river that had scared us months prior. This time, it offers the right amount of challenge. We’re rejuvenated by the area’s incredibly beautiful peaks, with glaciers calving directly into the river.

Completing the loop

It’s September now and we’re at the delta of the Copper River coming back toward the Lost Coast, which is showing itself in a different light. Salmon bump our boats as views of the snow-capped St. Elias mountains greet us on this sunny, warm day. The fireweed and strawberry leaves have turned red, adding color to an already beautiful scene. Learning from our previous mistakes, we wait out two storms instead of pushing through them. We’re lucky that they happen right as we’re staying in the only national forest hut in this area, and again later while we’re in a friendly fishing lodge.

We continue our journey back to Icy Bay on foot, where we had to quit and fly home so many months ago. A mile out, we feel the anticipation of our final destination as the tide is rising and the beach begins to shrink. Each wave touches our feet as we walk. Ricardo and I look at each other, agreeing silently to continue to the end tonight. Turning around while so close to Icy Bay is not an option.

Alaska has another plan for us. The tide rises quickly and we realize we'll be trapped if we continue walking the beach. Ricardo attempts an escape by climbing up a mud cliff about 10 feet high. He’s making good progress until his feet get stuck in sticky, muddy, glacial silt. The more he moves, the deeper his feet sink.

I try not to panic as waves splash my knees. Ricardo digs at his feet with his hands. The water is rising higher with each passing moment. Suddenly Ricardo breaks free, sliding down the cliff on his back. Humbled, we do what we should have done from the start: backtrack to where we can climb up to the forest. Ricardo strips his clothes at the first stream we pass. They’re so heavy with silt that they plummet to the ground.

In the morning we stand on the shore of Icy Bay. During our first attempt to cross this bay in May, the sky was gray with heavy rain, whitecaps and icebergs making the crossing impossible. This time, Mt. St. Elias thrones over us, the water is glassy, and two-story-tall icebergs tower above as we paddle. The crossing is a delight.

Crossing Icy Bay among two-story high icebergs on the Lost Coast during our last day.

Crossing Icy Bay among two-story high icebergs on the Lost Coast during our last day.

We camp one last night, making a fire on the beach and watching the sunset bathe the bay and mountains in pink. Sandhill cranes fly south over our heads. Like them, it is time for us to go home, having closed our loop at last. While we dream of fresh food and a shower, the thought of this journey ending feels bittersweet, like losing a friend.

Before leaving on this adventure, people often asked whether we were afraid this adventure would break us apart. Both leaders by spirit, we fought over decisions and who got to navigate. But slowly, over the months in Alaska, we learned to let each other lead – to make space for Ricardo’s need to push himself physically through long days and for my need to slow down and admire the wildflowers, lichen, and scenery. This journey has shown us that we are able to do so much more than we thought, both physically and mentally, as a team.

We watch the fire, both deep in our own thoughts. We completed the loop, but I am not ready to let go of this adventure. Plus, crossing the Brooks Range is still missing. As the sun dips below the horizon, I whisper to Ricardo “Next summer we return to Alaska, no?”

In 2023, Salomé and Ricardo returned to Alaska to connect Denali National Park to the Arctic, first biking to the Brooks Range, then hiking west through the mountains to the Noatak River to paddle to Kotzebue. They were once again humbled and invigorated by the adventure. You can read more at north2arctic.com.

This article is written by Salomé Stähli with Ricardo Martin Brualla.

This article originally appeared in our summer 2024 issue of Mountaineer magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, visit our magazine archive.

Salomé Stähli

Salomé Stähli