A musty odor wafts up as we descend the narrow, creaky staircase into the basement. I’m following a surefooted 92-year-old man down the steps and into a cold, well-lit room. Paint, brushes, books, and stacks of papers cover every available surface. “It’s here,” he says as he gestures me to follow him towards a large table.

Under a cloth-covered canvas is a portfolio that contains a watercolor he painted at 26,000 feet. “I think I can get in the Guinness Book of World records for this,” he says proudly as he carefully hands me the painting. “I painted it our tent during the storm.” He’s referring to the storm on the American Karakoram Expedition to K2 that gained fame not for summiting the peak but for an act of heroism and a single belay or as mountaineers around the world know it, “The Belay”.

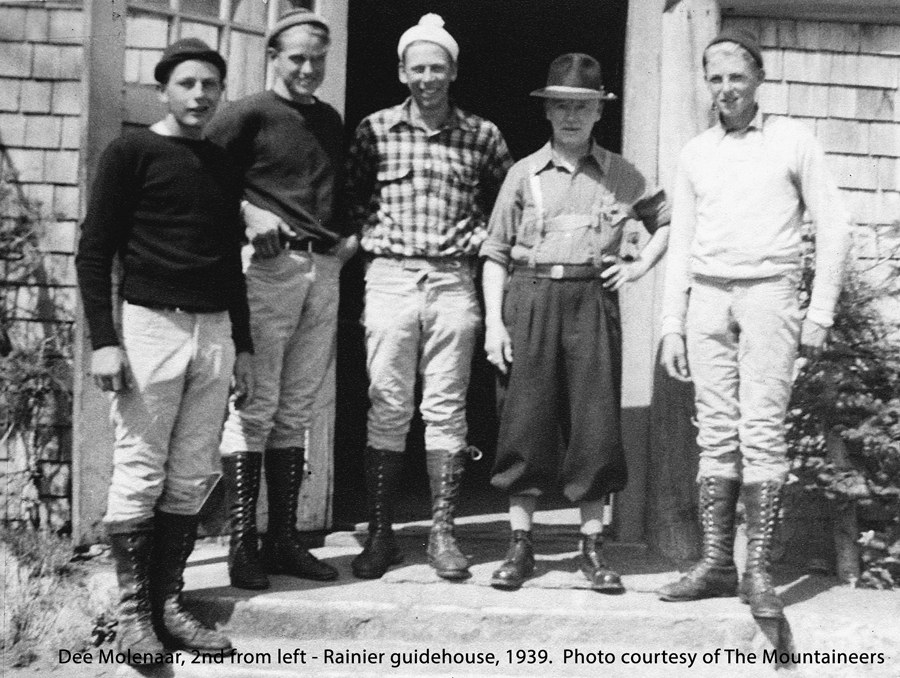

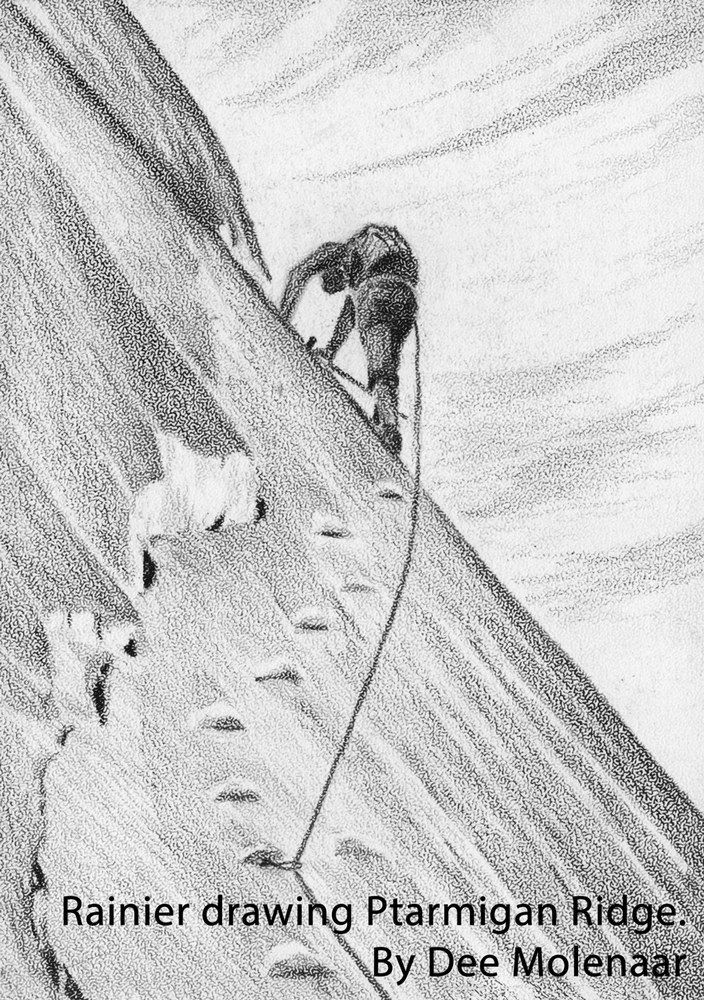

Six years later, at 98 years-old, legendary mountaineer and 75-year member Dee Molenaar may be the last surviving member of that 1953 K2 expedition. This month at our annual gala, The Mountaineers will present Molenaar with a Lifetime Achievement Award. And what a life it has been – pioneering routes on Mt. Rainier, the first ascent of a Canadian peak with Senator Robert Kennedy, and sharing a microphone with Sir Edmund Hillary during a radio broadcast. But among these adventures, one will surely stand the test of time and maintain legendary status.

In 1953, there had been very few attempts and only two successful climbs of 8,000-meter peaks, so no one knew much about the lethal effects of the thin air at those altitudes. Mountaineers didn't know that future generations would label altitudes of 26,000 feet and higher "The Death Zone" because the amount of oxygen is insufficient to sustain human life. At 28,253 feet, K2 is the second highest, most difficult mountain in the world to climb.

Dr. Charles Houston, Dee Molenaar, Art Gilkey, Bob Craig, Tony Streather, George Bell, Bob Bates and Pete Schoening attempted to climb K2 in 1953. The climbers reached nearly 26,000 feet but were trapped, confined to tents, by a violent storm. After nine days, Gilkey collapsed with a nagging leg cramp. Houston determined that Gilkey had blood clots in his left calf, a dangerous condition called thrombophlebitis. If a clot broke loose and reached his lungs, it could be fatal. His only chance was evacuation from Camp VIII, even in a blizzard.

With a unity of spirit and purpose, a heroic attempt was made to rescue Gilkey and get him down the mountain. They wrapped him in a sleeping bag and tent, and tried to rope-lower him down the route they had climbed, but were thwarted by avalanche danger.

The next afternoon, reaching 24,700 feet on unknown terrain down a ridge, the men were at the top of a steep gully leading to Camp VII. Schoening was lowering Gilkey, using his ice ax, driven behind a boulder, as an anchor. The rope ran over the boulder, around the ax and around his waist and hip to his hand.

Craig had moved to Camp VII to set up two tents. Five other climbers were divided among three ropes, two of which were tied to Gilkey. All were exhausted by effort and altitude when Bell slipped. He pulled Streather down onto the rope between Houston and Bates, knocking them off their feet, then Streather hit Molenaar. As they careened toward a cliff, their weight came across Gilkey and the rope to Schoening.

Schoening stood his ground and held the fall.

Houston was knocked out, three others injured. Craig, Bates, and Streather anchored Gilkey on the slope and helped set up the tents to regroup. When two returned for Gilkey, he was gone, apparently swept away in an avalanche.

What remains of the story is the tale of closeness and solidarity in great danger. The stuff of great legends. Houston concluded, “We all returned the very best of friends, and we remain the best of friends to this day.”

Many years later in 1970, in a letter to Charles Houston, Dee writes “I do appreciate your thoughts in sending that article and symbol of the close ties we developed on K2. I’ve since played back the tape copy of the base-camp recording; those weary voices really bring back fond memories. K2 1953 was the high point of my life in so many ways, and nothing will equal it. I’ve sometimes wondered in hindsight about whether or not our adventure really stacks up against the other famous mountain and arctic experiences of man.” Nearly 50 years later it’s safe to say it will.

Recognize Dee's Legacy in Person

Join us on March 18 as we honor mountaineering legend Dee Molenaar with The Mountaineers Lifetime Achievement Award.

Mary Hsue

Mary Hsue