by Steve Scher, UW teacher and former KUOW radio host

Endurance comes in many shapes and body sizes.

This was written for The Mountaineers, so named for those women and men, who, step by grueling step, through thinning and frigid air, conquer mountain tops. Endurance is at the core of the philosophy of the organization. Training at a level of diligence and pain that many would cringe at, mountaineers find the will, drawing from a reserve that powers the next step and the next.

I was in London, alongside the Thames, near Hampton Court Castle, when runner after runner swept past. A half-marathon was in progress. I stopped to watch. First came the elites: trim bodies, taught arms and legs — they seemed to shimmer as they passed, electrically charged.

Then came the middle passage: a little rounder, a little slower. Fatigue showed in their eyes, but not just fatigue. Determination too, and confidence. Runners who knew their pace; who knew their abilities.

Then came the last group: some untrained, some undisciplined, some unfocused, eyes staring out towards a distant finish - maybe a receding climax. Others followed; a man swinging on crutches, one leg reaching forward; a woman pumping along in her wheelchair; the thick, plodding legs of a teen, downs syndrome written across his eyes. All drawing from that same reserve. They push themselves because they can. Because, for them, it’s imperative. They must.

I was reporting from a poor neighborhood struggling to hold fast against the wealthy wave of glittering gentrification. A man told me the people living in his neighborhood have a pride in home they don’t want to lose and won’t because they are galvanized in a way to allow things to endure.

Explorer Ernest Shackleton’s men survived the harshest of climates in Antarctica. They were marooned in an icy sea, on a desolate stretch of shoreline, with faint hope for rescue, finding refuge in flimsy tents, in meager means. Some surely must’ve muttered that men were not made for a life such as this. But we are.

Shackleton, determined to keep his crew alive, surely must have stared up at the name etched across his ice-gripped ship to wonder if they could live up to its promise. Would they have the endurance to cross mountains and seas? They did. We remember. What they accomplished, endures.

By its very definition — the ability to do something unpleasant or difficult for a long time — endurance means pain and suffering of some measure. Faiths embrace endurance as a testament to that suffering, but to something more. Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, Judaism look at the pain as a path to joy, a path built on patience, strength, and confidence. When facing trials, we can give up in defeat, the new testament says, or increase our capacity. Buddhism argues that for his own sake and others, a man can know that his own endurance, his ability to patiently persevere, carries him through.

Turn it to joy.

Sounds hard.

The philosopher Camus wrote, “In the midst of winter, I finally learned there was in me an invincible summer.”

Beside me, as I write this, my mother is breathing her last breaths.

One hundred-years-old, she was born the year before the United States entered the Great War. In the 1880’s, her parents fled the Pale of Settlement, that area that jostled Jews between Poland, Russia, and Lithuania. Facing murder, rape or conscriptions, many Jews sought a new life in an unknown world. Her parents thrived and suffered. They raised a large family and built a business, only to see it subsumed in the destruction of the Great Depression.

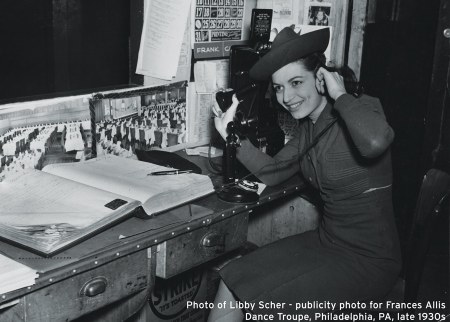

My mother came of age during that turmoil. Poor as they became, photos of her show a beautiful, stylish woman in smart hats and fashionable dresses that she had sewn herself. She helped her parents and helped herself by turning to the pleasures of dance. She built a strong body that carried her through a dancing career, a marriage, four children, musical reviews, PTA meetings, office work, not to mention a swirling world of war and peace, of space flight and cell phones. She treated her children with love and kindness and respect. She nursed my father through his last years and buried a daughter. Well into her eighties, she bowled in low 200s and well into her nineties, she practiced Tai Chi — though often from a sitting position.

In her last waking months, her mind slipping away, she often spoke in Yiddish. Not just in the funny phrases she had shared with my father — she spoke sentences, paragraphs, whole thoughts in a complete language she must have used with her parents — a language spoken in her childhood home.

I didn’t know she knew so much of it. Probably she didn’t know she had retained so much either, but she had. And when she spoke in Yiddish these past few weeks, she was speaking to her long-dead father, her long-dead sister — shades of memory that lingered in her heart as if still alive.

She isn’t speaking anymore, so deep is her sleep, so shallow her breath. But she is still there.

She made her way along the path, and now she is here, at that joy that is hers to claim. She faced the trials and tribulations of daily life with strength and confidence and an indefatigable will.

There is a symmetry in that. At our core, perhaps unknown to us, we have that endurance. We find it when we are looking, one grueling, beautiful step at a time.

Shortly after the writing of this piece, Steve’s mom, Libby Scher passed away, having lived (and endured) 100 years.

Steven Scher

Steven Scher