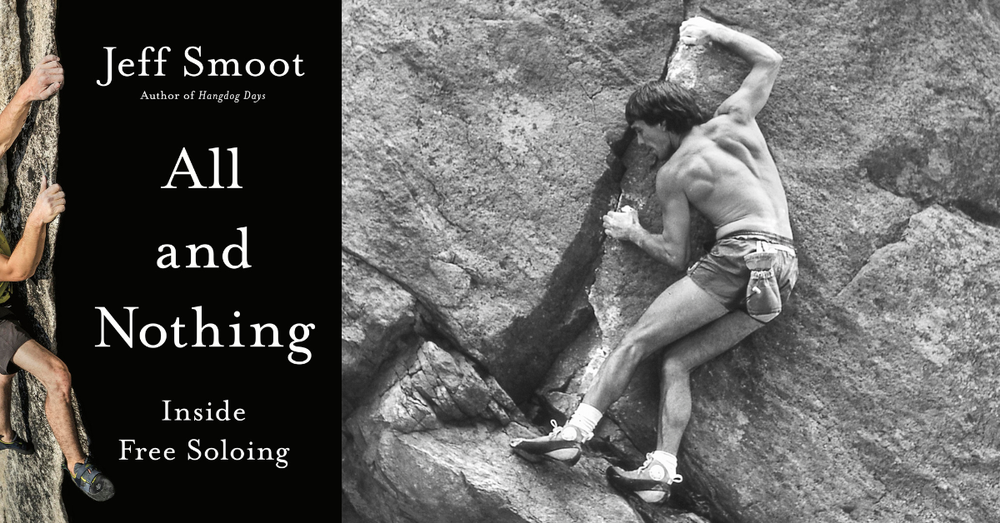

Excerpt from the introduction of All and Nothing: Inside Free Soloing by Jeff Smoot:

INTRODUCTION: "ARE YOU CRAZY?"

Humans have a primal fear of falling from high places. We are hardwired to avoid situations where we could fall to our deaths—when fear is punctuated with a jolt of adrenaline, it’s time to step back. This is why it’s such a thrill to ride the elevator to the top of the Empire State Building, walk across the Golden Gate Bridge, or creep up to the brink of Beachy Head. Of course, some people aren’t content to stand behind the railing enjoying the view; they want to edge closer, to feel the pull of the void.

In 2012, American skydiver Gary Connery jumped out of an airplane without a parachute and landed safely using a wingsuit. In 2016, Luke Aikins jumped without a parachute or wingsuit from a plane at an altitude of 25,000 feet and landed safely in a specially designed net. That same year, New Zealand free diver William Trubridge dove to a depth of 334 feet without the use of fins or an air tank or regulator, a discipline that requires intense mental focus. And in 2017, American rock climber Alex Honnold climbed the Freerider route on El Capitan, an iconic 3000-foot granite wall with a crux pitch rated 5.13a on the Yosemite Decimal Scale, in much the same way—without a rope or protective gear, just his hands, feet, rock shoes, and a chalk bag.

Honnold’s climb wasn’t the first big-wall free solo. Alexander Huber had free soloed the 1700-foot, 5.12a Brandler-Hasse Direttissima in the Italian Dolomites in 2002; Austrian climber Hansjörg Auer had free soloed a 2700- foot 5.12c route called Via Attraverso il Pesce in the Italian Dolomites in 2007; and, in February 2015, Brette Harrington had free soloed a 2500-foot 5.11a route called Chiaro di Luna on Aguja Saint Exupery in Patagonia. It also wasn’t the hardest free solo ever done. Huber had free soloed a 5.14a route called Kommunist at Austria’s Schleierwasserfall in 2004, and in 2008, Scottish climber Dave MacLeod had free soloed a route called Darwin Dixit rated 5.14b at Margalef, Spain.

What made Honnold’s solo of Freerider so noteworthy was the combination of the two—height and difficulty—a 3000-foot wall with continuously difficult climbing and a 5.13 crux 2000 feet off the ground. That, and the fact that it was the subject of an Academy Award–winning documentary, Free Solo, allowing everyone to vicariously experience that primal fear: if Honnold slipped just once, he would die.

WHEN SOMEONE FINDS OUT I’M a rock climber, they usually want to know my take on Free Solo.

Then they ask: “You don’t do that, do you?”

“Yes, I do,” I reply.

“Why would anybody do that?” they wonder. “Are you crazy?”

Most free soloists have had similar exchanges, been asked to justify their penchant for climbing without a rope. Some say they love the challenge of pitting themselves against nature; others say it’s the adrenaline rush they get while pushing themselves to their limit, or the dopamine high that follows. Still others say it’s the quasi-religious, Zen-like quality of pure focus they experience while climbing, of being in “flow,” in the “zone,” or “one with the rock.” Free soloing makes them feel part of a great cosmic unity of man and stone, grooving on the authentic experience realized only in that moment between life and death when all ego disappears, where they gain a fleeting, transcendental insight into some fundamental truth of life, or some such bullshit.

Some climbers don’t have a “why,” and instead say, “Why not?” or “Because you can’t.” They won’t say it’s the only thing that makes them happy, that the mundanity of “normal” life depresses them, or that the impulse to climb rocks without a rope because they want to, have to, no matter who might suffer, is the strongest one in their life. Nor will they admit that they are addicted to risk, compulsively putting themselves in perilous situations, lacking the control to stop even when they know better. And they won’t tell you they do it because they are self-centered assholes, although some of them may be.

Mark Twight, a prolific free soloist and extreme alpinist, thinks “why” is the wrong question entirely; he says we should be asking “not why, but how?” As in, how can we overcome our fear of death and enter a state of mind so focused that we not only survive a life-threatening ordeal but enjoy it?

Others, like John Long, longtime free soloist and editor of The High Lonesome: Epic Solo Climbing Stories, question the value of even asking the question. “There is no objective truth to any judgment per soloing, though some pronouncements sound better to our rational mind than others,” wrote Long. “But I do think that trying to derive some definitive statement about what soloing is, or should be, or can be, or shouldn’t be, is expecting too much of our quantitative skills.”

American psychologist Ernest Becker wrote about a professor of medieval history who had confessed that “the more he learned about the period, the less he was prepared to say [anything] about it.” Becker felt this sentiment also applied to his writing exploring the general theory of mental illness, especially when he was not himself a psychiatrist. “Why,” he asked, “should someone try to rake this area over again, in what can only be a superficial and simple-minded way?” to which he answered:

What I would like to do in these few pages is to run the risk of simple-mindedness in order to make some dent in the unintended imbecility brought about by specialization and its mountains of fact. Even if I succeed only poorly, it seems like a worthwhile barter . . . someone has to be willing to play the fool in order to relieve the general myopia.

Like Becker, I find myself wondering if I should be taking on the messy subject of free soloing, a practice that is perceived by many as “insane,” “suicidal,” or “a death wish” but defended by its proponents as a perfectly sane, rational, life-affirming activity, a subject that is so complex, with participants whose motives are so diverse and ineffable, that even one of the reigning experts believes defining it may very well be impossible.

Despite the inevitable criticism that such a work will engender, I am willing to play the fool. This book is my answer to those who ask, “Are you crazy?”

Mountaineers Books

Mountaineers Books