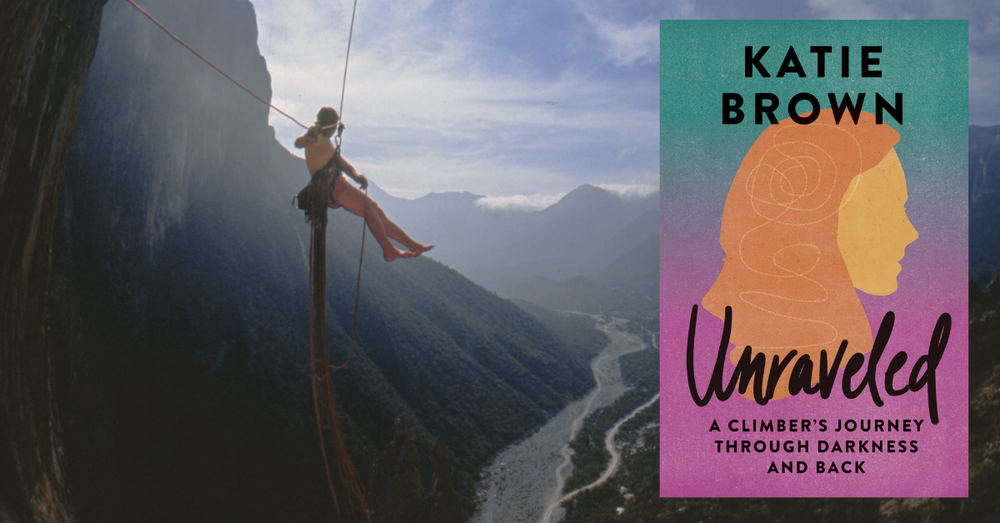

Enjoy the following excerpt from the prologue of Unraveled: A Climber's Journey Through Darkness and Back, by Katie Brown.

The scenery changed from flat, grassy fields to jagged, broken rock formations. Clutching the steering wheel tightly, I drove around a bend as the canyon narrowed. Occasionally, a house dotted the edge of the road. How fitting that my family had ended up living here, amid walls of unclimbable rock.

I was going too fast, pushing the accelerator and pulling out into the next straightaway, the speedometer shooting upward. I felt sure in my judgment of how to operate within my ability. That awareness had kept me safe my whole life, whether speeding through the canyon or climbing hundreds of feet above the ground. But everything else I was unsure of.

My car’s engine rumbled, mimicking the panic in my belly. At age twenty, I had won every national climbing competition I had ever entered, including a World Cup title and several international events. I’d become the first woman to climb 5.14 on my first try, graced the pages of Rolling Stone and the New York Times, and appeared on national television. In spite of my accomplishments, I was terrified. I was going to talk to my mom. About everything. I was more afraid of this single conversation than I had ever been of any climb or competition.

My new therapist had said that talking to my mom might help me find a way through the darkness I lived with. That if I confronted her, maybe a weight would be lifted.

“But I’m scared of how she will react,” I’d said. “You don’t know my mom. Sometimes, well, she’s really hard to talk to.”

“You are not responsible for her reaction,” the therapist responded soothingly. “You can only control your actions, not someone else’s response. Letting go and forgiving is about what you do—not what they do.”

“Ok,” I replied, still unsure.

“For you to be able to move on, I think you need to share with her how you feel. Then you won’t be carrying around this heavy load anymore. And you might be surprised at how she responds. She’s your mom, after all, and only wants the best for you.”

You mean she wishes she were me, I’d thought, before I could stop myself.

Nevertheless, there I was, driving up the canyon. I imagined a moment where I told her how I felt, and she apologized and told me it was ok. Maybe I’d feel something I’d never felt around a parent, something I imagined other children felt around their parents. Comfort. Safety.

For a moment, I felt hopeful. Excited even.

I pulled into the driveway of a house set so close to the road that the whine of passing traffic and joyriding motorcyclists provided constant background noise. The house was small and military green, with a flat front and asymmetrical peaked roof. Jagged concrete steps led up to a wire grate in front of the door. It tipped back and forth, clattering, as I stepped up to go inside.

From the entrance, I could see past the wood stove, into the kitchen. There used to be a wall blocking the view, but long ago my mom had taken a sledgehammer to the drywall, peeling it away to the studs to open the space and let in more light. Of course, the remodel had never been finished. She was waiting on my dad to complete it, and sometimes, I think it was the waiting that had driven her to madness.

“Mom!” I called into the backyard. She was pulling weeds, maniacally making a trail that would loop around the steep, unusable hillside. “Can I talk to you?”

She used a rope rigged with knots to descend the hill. We stepped into the house and settled in the kitchen, making tea with too much vanilla creamer, until it was sickly sweet. I wavered, unsure how to start, but finally blurted out what I had come to say.

“So, I don’t know if I told you, but I started seeing this therapist. She had this idea that I should talk to you about some stuff that’s been bugging me.”

Her eyes narrowed, her expression already defensive. “Is she a Christian?” “Huh? Yeah. Yeah, I found a Christian counselor.” I took a deep breath and dove in again, before I could chicken out. “Anyway, so you know how I had an eating disorder.”

“You didn’t have an eating disorder—you had Crohn’s disease.”

I took a step back. Although I had expected this response, it still shocked me. Already, confusion began to sprout in my mind.

“No Mom, I did. . . . I mean, I think I did.”

The truth that I had been so sure of only moments ago was slipping away. Was I crazy? Did I make that up? But no, no, I definitely had an eating disorder. If nothing else, I was sure of that one thing.

“Anyway,” I continued, shaking my head as though trying to dislodge water clogged in my ears, “sometimes I feel frustrated with how lost I feel right now. I get stuck on these moments growing up when there were opportunities I could have taken, but you know, I wasn’t allowed to . . .”

“So you think I ruined your life?” She cut me off, setting down her tea abruptly. It sloshed over the rim and onto the laminated counter. I looked at the fridge behind her, avoiding her eyes. Sometimes what I saw in them—well, to me, it felt like hate.

I had known this whole “confronting my mom” thing was a bad idea. The therapist had been wrong. Why didn’t I ever listen to my gut? It was as if my gut was broken in more ways than one. My heart started to flutter. I needed to get out of this situation.

Mountaineers Books

Mountaineers Books