"See that ledge that runs to the right from Lower Curtis Glacier?” Stewart pointed to the far slope behind him. “That is the intersection of two terranes. Shuksan greenschist is above the line, and Darrington phyllite is below it. A thrust fault runs between them." Stewart (his geology training evident), stood in front of us, pointing at diagrams in his notebook and then the cliff. We had stopped for lunch near Lake Ann. I stood off to the side, letting him talk. He teaches several courses for The Mountaineers, and I’d hoped he’d come on my trip. He could master this geology that I’d found so confusing. We’d seen so much thanks to him.

Basalt Lava flowed 300,000 years ago near where the Mountaineers Baker lodge now sits. The eruption happened before Mt. Baker had formed and created Table Mountain.

Basalt Lava flowed 300,000 years ago near where the Mountaineers Baker lodge now sits. The eruption happened before Mt. Baker had formed and created Table Mountain.

Four hours earlier, we had left Baker Lodge. Thick clouds obscured the view, and we could see neither Mount Baker nor Shuksan. The columnar basalt by the lodge’s parking lot made us pause. This flow also formed Table Mountain and happened about 300,000 years ago. The reddish leaves on the blueberries and mountain ash appeared warm in the soft filtered light. Besides all the living things we would identify, our goal was to explore the complex geology of the North Cascades.

Alpine Lady Fern in fall colors

Alpine Lady Fern in fall colors

Fall colors of moss and blueberries

Fall colors of moss and blueberries

The Lake Ann Trail dropped down into a broad valley. There, Stewart pulled out a map and a series of drawings while the rest of us formed a semicircle around him. The Shuksan Arm rose behind him and Ptarmigan Ridge behind us. Steep slopes with talus and tree thickets climbed a thousand feet. "With continental drift, the floor of the Pacific Ocean is pushed under the land," Stewart ran his finger over a drawing showing how the Pacific tectonic plate is subducted and melted. “The volcanoes, like Mt. Baker, are created where the molten rock reaches the surface. But, sometimes, there is a piece of the ocean crust that has a different consistency. It doesn't subduct," he said, pointing at the next figure in the briefing book that he'd made to help us understand these concepts. "These chunks are pressed up against the continent, sometimes lapping up and over some of the pieces already here. These new parts are called terranes, and we hope to see evidence of four of them that have happened over the last 100 to 200 million years.” His broad brim hat and thick beard made him look like an explorer and professor.

Naturalists hike through the bottom of a cirque. Pikas scurried through rocks, a mountain goat chewed its cud on the cliff, and mountain hemlocks dotted the valley. We repeatedly stepped over scat from the local bears that had fed on the abundant blueberries.

Naturalists hike through the bottom of a cirque. Pikas scurried through rocks, a mountain goat chewed its cud on the cliff, and mountain hemlocks dotted the valley. We repeatedly stepped over scat from the local bears that had fed on the abundant blueberries.

The Mushroom guru, Stewart, works to identify one with his newly minted key.

The Mushroom guru, Stewart, works to identify one with his newly minted key.

False Chanterelle Mushroom

False Chanterelle Mushroom

Iron probably runs through the rocks that were part of this landslide. Notice the smaller Mountain Hemlocks that fill the slide area and the larger ones on each edge. The landslide probably happened three or four decades ago.

Iron probably runs through the rocks that were part of this landslide. Notice the smaller Mountain Hemlocks that fill the slide area and the larger ones on each edge. The landslide probably happened three or four decades ago.

Clouds covered the tops of both ridges and totally obscured Mount Shuksan. Stewart explained that this massive mountain, pointing behind him, had once been basalt on the ocean floor. It had migrated, maybe thousands of miles, and had been taken deep into the earth where pressure and heat metamorphosed the basalt into greenschist and then it came back up, resting here. Greenschist is hard and resists erosion. Stewart’s hat cast a shadow on his face; his enthusiasm was infectious. He pointed to different geologic features around us, explaining what we were seeing. When he paused, there was silence as everyone tried to absorb the magnitude of how dynamic this landscape was. These timescales are hard to fathom. Then the discussion continued for twenty minutes before we began to hike again.

Hiking through the giant cirque that comes down from the Lake Ann Trailhead. Swift Creek now flows through this valley. From a distance, the valley shows the typical U-shape of a Pleistocene glacier that carved its wall. Just 20 millennia ago several hundred feet of ice would have been above our heads.

Hiking through the giant cirque that comes down from the Lake Ann Trailhead. Swift Creek now flows through this valley. From a distance, the valley shows the typical U-shape of a Pleistocene glacier that carved its wall. Just 20 millennia ago several hundred feet of ice would have been above our heads.

The trail toward the saddle into Lake Ann climbed steeply through a talus slope of granite. Stopping, we huddled while pikas scolded us. Here was a relatively recent geologic event. Just two million years ago, a molten plume squeezed up between older rocks but didn't break the surface. It cooled slowly, forming granite, and now the overlying material had eroded, exposing the granite. Stewart explained the crystal formation that makes it and how other igneous rocks have different mineral compositions.

The ash cliffs of the Kulshan Caldera rise on the far wall beyond Swift Creek. Granite rubble from the Lake Ann pluton covers the close slope.

The ash cliffs of the Kulshan Caldera rise on the far wall beyond Swift Creek. Granite rubble from the Lake Ann pluton covers the close slope.

Across Swift Creek, white soft-textured cliffs hung halfway up the slope. These were carved from the ash beds of the Kulshan Caldera. That volcano exploded in a cataclysmic eruption 1.1 million years ago, then died. The massive caldera is more than 5.6 miles long and 3 miles wide, an area a little smaller than Olympia, Washington. We stood just outside of its boundary, trying to imagine the explosion — the hole, 3 miles deep, filled with rhyolite ash that solidified into rock. The Table Mountain lava flow happened more recently and put a cap across part of the caldera.

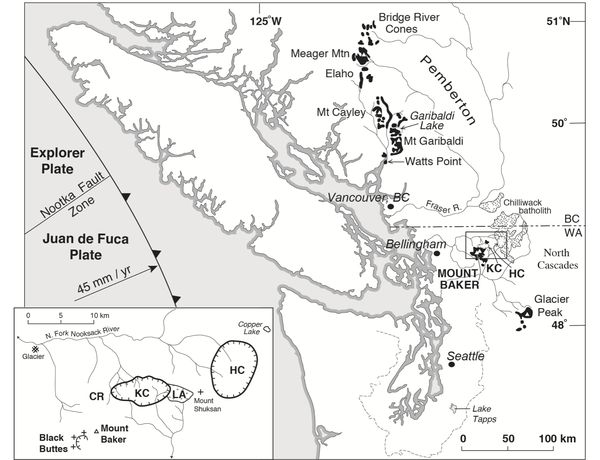

A regional map of the North Cascades produced by USGS showing the location of active volcanic areas. The insert shows the progression of activity in the wider Mt. Baker region.

A regional map of the North Cascades produced by USGS showing the location of active volcanic areas. The insert shows the progression of activity in the wider Mt. Baker region.

I stood staring back and forth from the wall of the Kulshan Caldera to the granite outcrop of the Lake Ann Pluton trying to absorb the volcanism of this area. Over the last 4 million years, the volcanic field here had slowly migrated southwestward. First, the area around the Hannagan Caldera was active. That remnant structure was created about 3.7 million years ago. It is about 5 km northeast of where we stood. Then came the formation of the Lake Ann Pluton. Geologists can’t tell if the Lake Ann bulge ever reached the surface. The repeated waves of glaciation would have scraped away volcanic ash and less hard rocks. Next came the most massive explosion, when the Kulshan caldera formed. The Black Buttes stratocone area was active from half a million to about a quarter-million years ago. It is a little southwest of Mt. Baker. Then for the past 140 thousand years, Mt. Baker has been active with its most intensive period from 40,000 years ago to about 12,000. Other smaller eruptions took place throughout this area when small vents opened here or there. Our group had continued up the trail, so I turned to hurry.

Banded Chert: Sedimentary rock formed from the siliceous skeletons of marine plankton. The chert had been metamorphosed under pressure and heat. Near Mt. Shuksan it is a common component of the Bell Pass Melange and littered the slope up to the Lake Ann Saddle.

Banded Chert: Sedimentary rock formed from the siliceous skeletons of marine plankton. The chert had been metamorphosed under pressure and heat. Near Mt. Shuksan it is a common component of the Bell Pass Melange and littered the slope up to the Lake Ann Saddle.

As we climbed up and then over the saddle to Lake Ann, rocks that almost looked like petrified wood littered the slope. These were banded chert, a metamorphic rock formed in the ocean and brought to the North Cascades in one of those terranes. Eons ago, the skeletons of millions of microscopic marine plankton had settled to the ocean floor, became sandstone-like and then went through a deep dive into the earth’s crust to re-merge as these fascinating rocks. Repeatedly, I ran my fingers along the lines, and now many of us sat on chunks of chert while we listened to Stewart.

In view was the history of this planet. Stewart explained that continental drift brought four successive rock waves that were thrust up against the land and stacked on top of each other. Each extended the coast of Washington westward. On the far cliff, those plates were visible and tilted to the southeast. During much of this history, volcanism had been here too. A piece of the Lake Ann Pluton was on the surface right below the glacier. That morning, we’d hiked through 225 million years of the earth’s past.

The Lower Curtis Glacier draps over the wall on the upper left. The green mustache along the cliff running out from the glacier marks the boundary between two terranes. Darrington phyllite is below the line, and Mt. Shuksan greenschist is above it. The Lake Ann pluton is right below the tip of Curtis Glacier. The Bell Pass Melange is below the phyllite layer and is full of banded chert.

The Lower Curtis Glacier draps over the wall on the upper left. The green mustache along the cliff running out from the glacier marks the boundary between two terranes. Darrington phyllite is below the line, and Mt. Shuksan greenschist is above it. The Lake Ann pluton is right below the tip of Curtis Glacier. The Bell Pass Melange is below the phyllite layer and is full of banded chert.

Add a comment

Log in to add comments.Excellent entry, thanks!

Thanks so much.

Thomas Bancroft

Thomas Bancroft