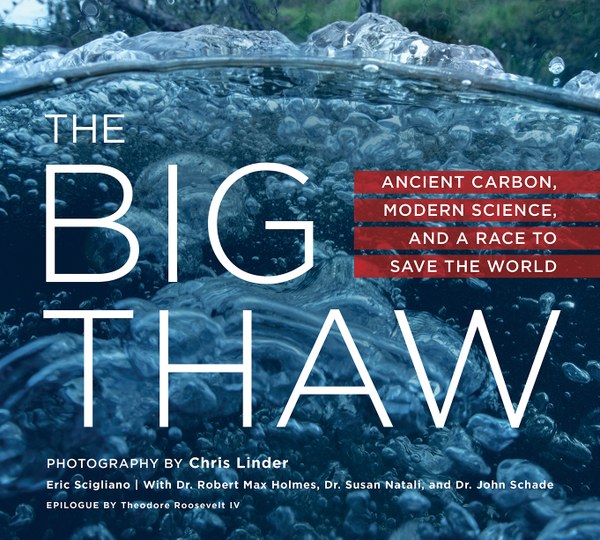

The Big Thaw: Ancient Carbon, Modern Science, and Race to Save the World introduces the scientists and students studying Arctic permafrost and what it contains: a vast store of ancient carbon, more than four times the quantity found in all of today's forests, a ticking carbon bomb releasing carbon dioxide and methane as the permafrost thaws. Through Chris Linder's stunning photographs, we meet the people and processes at work across remarkable Arctic landscapes from Siberia to Alaska's Y-K Delta.

The following is excerpted and adapted from Chris Linder's "Notes from the Field" in The Big Thaw. Chris, along with lead scientist Dr. Max Holmes, will join us on November 21 at our Seattle Program Center to discuss thawing permafrost and its role in the climate crisis.

As the formerly firm permafrost soil beneath them thaws, larch trees fall into a Siberian lake while methane bubbles up from the lake's bottom (Photo by Chris Linder)

As the formerly firm permafrost soil beneath them thaws, larch trees fall into a Siberian lake while methane bubbles up from the lake's bottom (Photo by Chris Linder)

Notes from the Field

By Chris Linder

Mud and invisible gas. I’m not sure there are two less photogenic (or difficult!) things to photograph, but they are central characters in this story. Permafrost is best appreciated through senses other than sight; it feels like frozen cement in your hand when you chisel it out of the ground, and when it thaws, it oozes like chocolate pudding. It has a rich, earthy smell, like freshly turned soil in a farmer’s field. But to the eye, it doesn’t look a whole lot different from the mud pies my kids made as toddlers. Methane and carbon dioxide gases are the by-products of microbes that eat the carbon contained in permafrost, but they are completely invisible...unless you watch them bubble up from the bottom of an Arctic lake.

After completing a number of expeditions to both the Arctic and Antarctica, a program manager at the National Science Foundation encouraged me to talk with Dr. Max Holmes from the Woods Hole Research Center (WHRC). Max, a river chemist specializing in the Arctic, had just been funded to create a new field program for undergraduates in Siberia. Max is the kind of person who fills a room—his enthusiasm and complete devotion to his work are infectious. By the time he finished explaining the Polaris Project to me in his office, I had agreed to join the team as the expedition photographer. Little did I know that over the next ten years, I would be making seven trips to the Siberian and Alaskan Arctic to photograph the Polaris Project.

Max Holmes returns to camp after a long day in the field (Photo by Chris Linder)

Max Holmes returns to camp after a long day in the field (Photo by Chris Linder)

After my first frustrating summer photographing this project, I realized I needed to start thinking outside the box. I invested in two new pieces of equipment: an underwater housing for my camera and a wetsuit—because Arctic lakes and rivers, even in summer, are cold. This opened up a whole new perspective for me. Now I could be in the river as researchers leaned over the sides of the aluminum speedboats and collected water samples. I could capture those huge clouds of methane I saw escaping from the bottom of the lakes. As an added bonus, I found the wetsuit’s neoprene was thick enough to repel even the most persistent mosquito.

The next toughest part of my job was just being in the right place at the right time. Summer in the Arctic means twenty-four hours of daylight, with the best light happening when most sane people are sleeping. Capturing both the science team in action and the peak landscape light meant eighteen-hour workdays for me. My daily routine went something like this: follow researchers from 8:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m., sleep for a few hours, shoot landscapes from 11:00 p.m. to 3:00 a.m., sleep for a few more hours, and crawl back out of bed at 7:00 a.m.

There’s something nourishing about Arctic light, though. It washes away weariness nearly as well as a good night’s sleep. Sitting on a bluff over the Kolyma River watching the sun scoot sideways between distant peaks, I couldn’t imagine missing one second of every three-hour sunset or sunrise.

The sun shines through the cottongrass on a windy day near Cherskiy (Photo by Chris Linder)

The sun shines through the cottongrass on a windy day near Cherskiy (Photo by Chris Linder)

On Taiga and Tundra

It’s midnight, and the sun has just started to tiptoe across the tops of the larch trees on the western bank of the Kolyma River. The horizon glows orange, fading to a deep purple in the clear sky above. The river is wide here, and the orderly line of treetops on the far bank, tiny in the distance, looks like the teeth of a long zipper. On the deck of our floating dormitory/laboratory (a repurposed Soviet-era barge), undergraduate students, scientists, and our Russian hosts chat excitedly and snap photos in the warm sunset light. It’s the start of a Polaris research experience: we are headed north, toward the Arctic Ocean, for an expedition to study the Arctic tundra.

As we motor down the mighty Kolyma, the taiga forest rolls endlessly by. The sun never quite makes it behind the trees. After dipping teasingly low, it jumps right back up into the sky, filling the barge with an orange glow. By the time breakfast—a hot, salty, buttery gruel and homemade bread made by our Russian cook—is served eight hours later, the landscape finally shows signs of change.

Wildflowers bloom on a cliff top along the Kolyma River, Siberia (Photo by Chris Linder)

Wildflowers bloom on a cliff top along the Kolyma River, Siberia (Photo by Chris Linder)

The thick stands of larch trees thin and shrink. Soon, only a few twisted and ancient trees barely taller than a toddler can be seen among the rolling green expanse of the Arctic tundra. The tundra...I had expected a bleak, featureless environment sculpted by the cold and wind and harboring only a handful of plant and animal species.

But when we finally anchor the barge on a sandbar and bound up the nearby bluff, a new panorama in miniature is revealed at our feet. On the ridges of the gently undulating landscape, dwarf willow and birch shrubs only a few inches high form a spongy green mat. Tiny blossoms of white and fragrant Labrador tea (the leaves, when crushed, smell like Christmas trees), blue forget-me-nots, delicate white and pink Indian paintbrush, and purple thyme dot the green like stars. Descending into the shallowly sloping valleys where water pools and trickles in tiny rills on top of the permafrost, foot-tall tussock mounds topped with the white balls of cottongrass dance in the breeze. Farther in the distance, abutting the banks of the river, thousands of shallow pools and floating vegetation form an intricate mosaic. This is a landscape defined by extremes in scale: endless grandeur and minute detail.

Polaris students hike along the bank of the Kolyma River, Siberia (Photo by Chris Linder)

Polaris students hike along the bank of the Kolyma River, Siberia (Photo by Chris Linder)

Hope for the Future

At the end of my first summer in Siberia, I remember having dinner in the city of Yakutsk with the science team, and one of the faculty members asked me if I was going to come back the next year. Without hesitation, I said that nothing could entice me to come back to that buggy swamp.

But over the next year, as I spent hours, days, and weeks editing interviews that I had conducted with the undergraduates and producing short multimedia videos for the Polaris website, the consequence of this project started to sink in. In just four short weeks, Polaris had clearly made a tremendous impact on the students.

Polaris student and Alaska Native Darcy Peter collects soil samples in the Y-K Delta (Photo by Chris Linder)

Polaris student and Alaska Native Darcy Peter collects soil samples in the Y-K Delta (Photo by Chris Linder)

The process of designing their own field research and getting answers to big questions about climate change had literally changed their life trajectories. When I found out that four of the students had applied to come back in 2010 to continue their research and mentor the new students, I knew I had to come back as well and continue to document this critical juncture in their lives.

Climate change and its many global repercussions will be their generation’s challenge to solve. Just being around these undergrads, watching as they come to grips with that reality, and seeing them rise to the task with enthusiasm and optimism—that’s what really gives me hope. And so, with my own grim determination, I have put on that head net and battled the bugs for seven seasons to tell their story.

On November 21 at 7pm, join Chris Linder and Dr. Robert Max Holmes from Woods Hole Research Center, contributors to The Big Thaw: Ancient Carbon, Modern Science and A Race to Save the World, at our Seattle Program Center. The evening will include a multimedia presentation going behind-the-scenes from eight field seasons at work in Siberia and Alaska followed by a panel discussion with regional climate leaders, featuring:

- Phil North, conservation scientist with the Tulalip Tribes

- KC Golden, board chair of 350.org.

Chris Linder

Chris Linder