I got my first snowmachine when I was two, my first ATV when I was four, and my first gun when I was nine. My snowmachine was an Arctic Cat “Kitty Cat,” a real, gas-drinking motorized vehicle, miniaturized with a 90s brand of teal and purple striping on black casing. The ATV – four wheels for four years – was a zippy red Suzuki. My first gun was a BB.

In the way that other kids may grow into larger violins or skis, I got bigger and faster machines. To be clear, my family wasn’t wealthy. But this is how it’s often done in my birthplace: as necessary as replacing a kid’s outgrown shoes and jackets.

Growing up in Alaska, my family wasn’t outdoorsy in the environmentally aware or fitness-focused sense. We didn’t backpack or trail run. We’d never heard of the phrase “Leave No Trace.” But we were always outside. My dad’s paternal grandfather, a German farming immigrant, homesteaded near Point MacKenzie, Alaska and built a series of cabins on the land. As a kid, we were at the homestead nearly every weekend. As much as I loved school, I would count down the hours until the Friday bell and race home to load up the truck with my dad. We were always joined by our husky mix Riley, who on reflection was maybe a coyote.

Once at the cabin, we’d eat junk food while waiting for our wood stove to heat up the cabin’s interior (it took hours). My mom and younger sister would arrive the next day, already a snowmachine ride and a moose sausage behind. Our cabin, which my dad built by hand, wasn’t like the nicer “cabins” (fancy houses that happen to be in the woods) I’ve visited as an adult. We used a generator and kerosene lamps for electricity and the roads were unpaved dirt. Ours was a truly remote and rugged experience. I loved it.

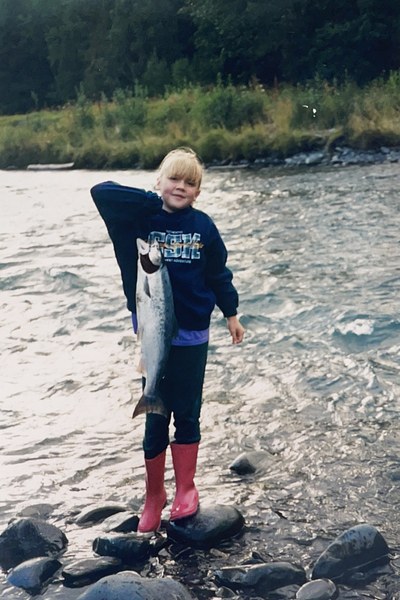

Brianna fishing for salmon at Bird Creek, Alaska, circa 1998.

Brianna fishing for salmon at Bird Creek, Alaska, circa 1998.

Brianna's mom and dad at their cabin, circa 2000.

Brianna's mom and dad at their cabin, circa 2000.

The last frontier

While we spent every weekend at the cabin, we lived in Anchorage — the biggest city in Alaska, hosting half of the then-600,000-person population — which falls somewhere between a small town, a suburb, and a nature preserve. Think open space, strip malls, and a decent-sized city center immediately surrounded by mountains on the east and ocean to the west. Anchorage is not rural in the extreme sense, but the boundaries between nature and city are impossibly blurred: moose and bears casually cross streets and lounge in backyard pools, houses back up to undeveloped forests, bike paths and trail systems run through the city and stretch up to the foothills. You can literally run from your house into the mountains.

An Alaskan life is highly tied to nature, regardless of whether you live in the backwoods or the city. Even for those who have never gone camping or skiing, living in Anchorage necessitates an exposure to harsh weather, long winters, and wildlife, whether welcome or not. This can make life difficult — shoveling feet of overnight snow from your car roof in zero degrees, moose-proofing your trees from bark-stripping teeth, and making sure your trash cans don't become bear bait. My own grandma, at 82, inexplicably survived a moose attack in Anchorage while walking in a wooded park.

Despite being a bookish kid who might have otherwise been inclined toward an indoor lifestyle, nature was my playground. My sister and I built snow caves in our yard (piled higher by my dad’s plow), imitated Steve Irwin in the woods behind our house (sadly, Alaska only has two types of frogs, so the similarity to Australia was limited), and biked the neighborhood late into summer nights when the sun hardly sets. In high school, instead of drinking at parties, my friends and I would go sledding and set up orienteering courses. An engineer-minded friend once fashioned his own snowshoes out of wire, wood, and plastic bags, which we tested in a steep, snowy valley. Although my earliest outdoor experiences weren’t motivated by exercise or any environmental agenda, they instilled a deep-seated love for being outside and embracing snow, wildlife, and the necessity of donning a full snowsuit just to walk the dog.

Brianna fishing for salmon at Bird Creek, Alaska with her dad and sister, circa 1997.

Brianna fishing for salmon at Bird Creek, Alaska with her dad and sister, circa 1997.

Brianna riding on her dad's snowmachine at the cabin, circa 1995.

Brianna riding on her dad's snowmachine at the cabin, circa 1995.

Rugged beginnings

Sometime around middle school, I graduated from the BB gun to a .22. Despite what many hardline, anti-gun proponents might think, receiving a gun at nine wasn’t necessarily a reckless operation. My dad was extremely strict with firearm use. He’d supervise while we practiced shooting cans and targets, providing militant angles and invisible planes that we weren’t allowed to cross with our gun barrel. I never had an interest in hunting (although I did work as a commercial salmon fishing deckhand for several summers), but my dad was a hunter: mostly moose and elk, and always for food. A moose processed and frozen into sausage and jerky would last the family all winter. And while the cabin was adorned with huge, taxidermized antlered heads, my dad abhorred trophy hunting. I will always remember my dad’s disgust when the neighbor came home with a young bear carcass. He was appalled that someone would be proud enough to kill a baby bear. "Not even good meat," my dad said.

You might assume that someone who hunts doesn’t care about animals, but I’ve found that people who hunt their own food sometimes appreciate animals even more. My dad is a softie for moose: he’s called me in tears upon seeing a moose killed by a car (which is sadly common in Alaska). Another time he almost got trampled by an agitated mother moose while trying to lift and return her trapped calf.

Despite his tree-clearing-for-roads and beer-drinking-around-a-campfire ways, my dad has never left a piece of trash on the ground; never taken something from the environment he didn’t need. Maybe not “Leave No Trace,” but a “Cause No Unnecessary Harm” mindset that he’s passed to me. As a kid, we didn’t think about the environment from a politically correct, conservational mindset, but my inherent exposure to and reliance on the outdoors instilled a natural desire to love and protect the environment, which I’ve carried with me throughout adulthood.

Brianna taking a break after a muddy ride on her four-wheeler.

Brianna taking a break after a muddy ride on her four-wheeler.

A moose outside the front window in Anchorage.

A moose outside the front window in Anchorage.

A changing outdoor mindset

As I grew up and surrounded myself with more athletic friends, it became clear that I came from a very different outdoor breed. My friends’ parents were former college skiers and planned backpacking trips with their kids, while mine shot guns and fireworks around a campfire. As I hit middle school, my relationship to the outdoors evolved. I started Nordic skiing, swapped ATV rides for runs, and collected animal skulls to study as a burgeoning biologist rather than to hang on the walls. By high school, I was an obsessive distance runner and cross-country skier (although, not having been enrolled in lessons as a kid like my friends, my skiing technique never quite caught up to theirs). I still visited the cabin and rode machines, but inclined toward what felt like a more refined outdoor lifestyle.

In college, a series of events led my dad to sell our cabin, which was devastating to our family and widened the rift between my former outdoor life and my new one. I attended a liberal arts school and became further aligned with the crunchy side of outdoors: leading backpacking trips and getting involved with environmental causes. I learned about factory farming and stopped eating meat, which, 14 years later, I haven’t resumed. I never rode another snowmachine (although the smell of exhaust still triggers the most visceral sensory nostalgia I’ve ever experienced) and never returned to the homestead.

This mindset shift was partially a natural evolution toward a low-impact outdoor life and partially pretention. I didn’t ride engines up mountains, I walked up them (conveniently ignoring the impact of driving cars to the mountains). Nature was no longer just the backdrop to my activities, but the reason I ventured outside in the first place. I began referring to my childhood as my “sledneck past.” A you-can’t-make-this[1]up Alaska party trick about getting a snowmachine before I got a bike, nothing more. However, I’ve been reflecting on my “alternative” outdoor path and how it led me to the ways I enjoy nature today, and more importantly how the outdoors, however they are used, can be a bridge between different political and cultural groups.

Brianna Nordic skiing with her greyhound, Javier.

Brianna Nordic skiing with her greyhound, Javier.

Common ground

I often find myself stereotyping Alaska as having two major factions: a gun-shooting, game hunting, snowmachine-riding majority, with environmentalists and outdoor athletes making up the “granola” minority. This is reductive (my family is an example of this intersection) and I don’t mean to suggest that one type treats the environment worse. But it's fair to say these groups use the outdoors differently, and these disparate attitudes often contribute to larger, widening ideological rifts across the country. I see it happen on a local level here in Washington: in our Sno-Parks, shared between snowmachine riders, dogsledders, and the “human-powered” snowshoers and skiers, recreationists fight over access and infrastructure, making judgements about the right way to use the outdoors. I’ve contributed to this at times in my evolution from a gun-shooting sledneck to an endurance sports-loving vegetarian.

But the thing about these two factions is that no matter how different they may seem, their common ground has always been the outdoors. A salmon fisher might revere Alaska’s waters for the food they provide, while a kayaker appreciates the serenity of a glacier-lined paddle. And yet, both love and care for the water.

Brianna (left) and her friend Mariah Nordic skiing in Anchorage, 2023.

Brianna (left) and her friend Mariah Nordic skiing in Anchorage, 2023.

Many ways to love the outdoors

Disparate backgrounds often lead people to the same destination for different reasons. While I have many privileges that allow me to participate in outdoor activities now (whiteness, most of all, as well as having an able body and the funds to take time off and buy gear), my childhood is proof that that not all outdoor recreationalists are wealthy elitists who grew up with posh, sporty parents who funded ski lessons.

There’s a tendency to police who has the “right” type of outdoor background, whether it was a childhood skiing expensive resorts in Aspen, shooting guns, enjoying urban parks, or having no outdoor luxuries at all. For many of us, these early “alternative” nature experiences — or the lack of outdoor access — are what compel us to pursue both outdoor recreation and conservation today. Many of us come from humble childhoods, compelled by our common love of nature to pursue the outdoors. For me, that meant slowly accumulating used gear over many years and learning to ski and backpack as an adult through subsidized, education-focused outdoor groups. Others are outside out of necessity or to sustain cultural and traditional lifeways. Thousands of Americans, often non-white, cannot simply choose to go outside, at least safely or enjoyably. Conversely, where nature is abundant, many rural communities suffer inverse consequences of isolation and poverty.

All people deserve the outdoors, however they want to use it. I believe in reasonable restrictions to prevent harm to the environment and those who dwell there — there’s no outdoors for anyone if we destroy it — but does it really matter if I want to hike and you want to dirt bike? Or if I like to run to stay fit and see the mountains and you like to hunt? Maybe the sledders should think more long-term about sustainability, resource management, and LNT principles. Maybe the anti-hunters should reconsider their own reliance on factory-farmed meat and weigh the benefits of responsible hunting. Maybe hikers and skiers should assess their condescension about motor sports and recognize not everyone is able-bodied enough (nor wants) to trek outdoors on their legs. We must stop policing who is best fit to enjoy the outdoors because we need more, not fewer, people engaged in the environment if we have any chance of protecting it.

Would I have ended up so outdoorsy had I grown up outside Alaska? I can’t say. But I do know that my outdoor childhood was a positive force. I no longer own a gun or eat meat, and I may have become a bit of an “earn your turns snob,” but I value my roots as a backwoods Alaskan kid more than any other experience in my life because it’s pointed me toward the nature-minded life that I’m privileged to lead now. So this winter, while I stick to cross-country skiing on the multi-use trails, I’ll admire the husky dogsled teams who remind me of my dog Riley and wave to the machine-sledders, taking an extra nostalgic sniff as they scream past.

This article originally appeared in our winter 2024 issue of Mountaineer magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, visit our magazine archive.

Brianna Traxinger

Brianna Traxinger