Jeff Smoot is the author of Hangdog Days: Conflict, Change, and the Race for 5.14, a fast-paced history-cum-memoir about rock climbing in the late '70s and early '80s—a pivotal and contentious time.

Note - Don't miss Jeff's free web PRESENTATION,

March 26, 6pm PDT. SAVE YOUR SEAT today!

In this excerpt from Hangdog Days, Jeff shares Peter Croft's memorable arrival in Yosemite.

A Ripple on the Pond

“So, Michael,” I began. I was back at the pay phone, ringing up Michael Kennedy at Climbing again. “Peter Croft is here. He showed up yesterday and soloed the Northeast Buttress of Higher Cathedral Rock, Braille Book, and Central Pillar of Frenzy, on his first day here, after driving all night from Canada. Do you want me to interview him, too?”

“Sure,” Michael said without hesitation. “Do it.”

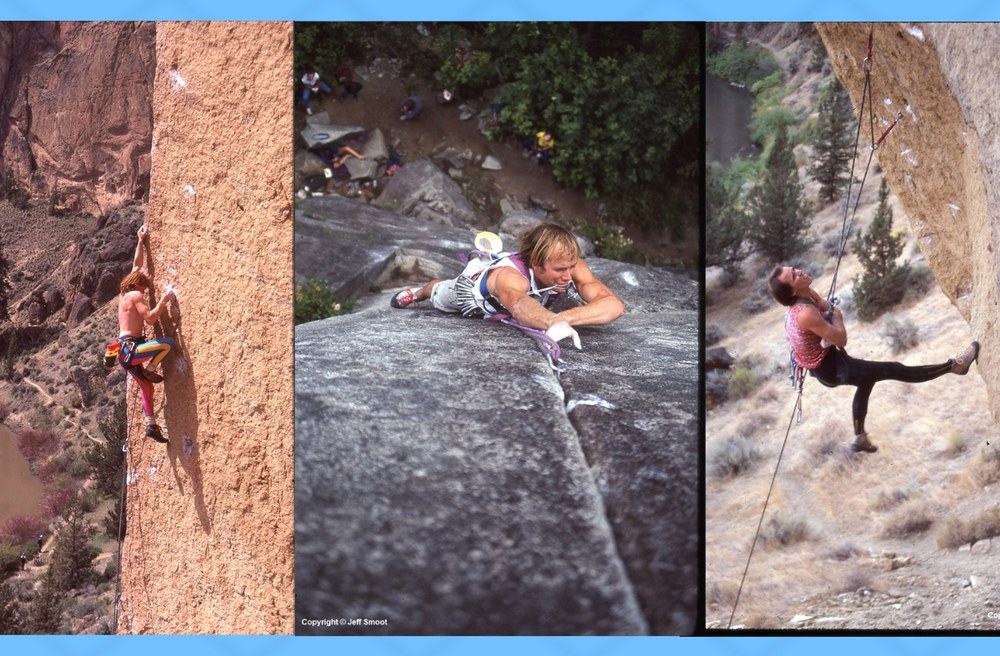

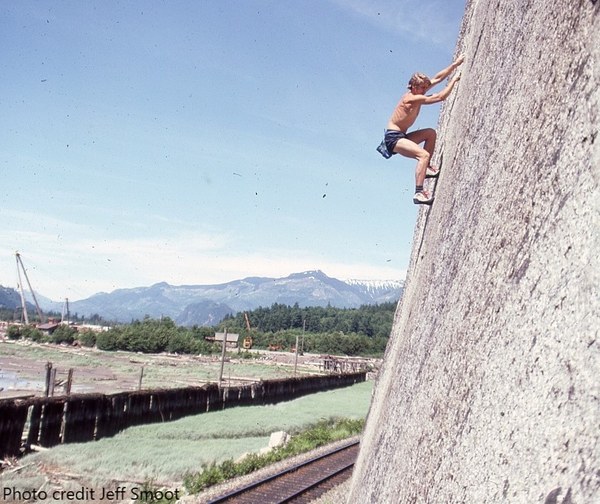

I knew Peter Croft by reputation before he arrived in Yosemite in May 1985. His 1982 free ascents of University Wall, an eight-pitch 5.12 route, with Hamish Fraser and Greg Foweraker, and Zombie Roof, a thirty-foot horizontal roof crack rated “5.12+,” both in Squamish, were widely known, at least in the Pacific Northwest. Croft, a Canadian, had done most of the hardest first ascents on Washington rock to date, and was probably the best climber in the state on any day he deigned to visit. I was always hearing about how he had climbed this roof or that crack at Index or Leavenworth, usually a new 5.11 or 5.12 route, an obvious plum that he had breezed in and climbed while we Washington climbers were asleep at the switch. To me he was already a local legend, but to the rest of the climbing world he was just getting started.

The previous year, Croft had become a blip on everybody’s radar when he soloed the Northeast Buttress and the Steck-Salathé in the same day, one of the more notable solo link-ups yet done in the Valley. Royal Robbins had called Henry Barber’s 1973 free-solo ascent of the Steck-Salathé “an act of vision.” The way Croft was climbing, he seemed to have more than vision; he had ESP.

The buzz around Camp 4 the night after he arrived was that Croft had driven all night to Yosemite from Squamish and then immediately gone on a rash of free-solo climbs. Upon rolling in late in the morning, he jumped out of the car and free soloed the Northeast Buttress of Higher Cathedral Rock, a 900-foot-high 5.9 route, then Braille Book, a 600-foot 5.8 route, and as a finale, he flew up the first five pitches of Central Pillar of Frenzy, another 500 feet of 5.9 crack climbing. He did it all during a rainstorm that had driven me and most other climbers off the rock that day. These weren’t the hardest routes in Yosemite, but the idea of driving twenty straight hours and then racing up 2,000 vertical feet of 5.8 and 5.9 rock, unroped and in marginal weather, sent a ripple across the Valley. We all heard about it, and we were all impressed.

Back home, Croft regularly soloed miles of 5.10 and 5.11 routes in a day. Literally. One Saturday I had witnessed him soloing Castle Rock in Leavenworth—600 feet up, 600 feet down. He did it ten times, which added up to 12,000 feet of vertical and overhanging rock up to 5.11 in difficulty before lunchtime. Hell, he’d even free soloed ROTC, a 5.11c overhanging thin crack at Midnight Rock. It was mind-blowing stuff. I wasn’t sure if anybody else in Yosemite knew what Peter was capable of, but by the time I interviewed him, everybody knew. By then, he had linked up the Northeast Buttress, the Steck-Salathé, and Snake Dike on Half Dome in a single day, one of the most impressive Yosemite enchainments yet done. They epitomized Croft’s approach: get in as much climbing as possible in a day and on as much terrain as possible, whether 5.2 or 5.10. Climbing solo is far faster than climbing with a partner, so when faced with the choice of working on a 5.13 route all day or linking up a series of long 5.9 routes high in the mountains, Croft always opted for the latter. He climbed hard; he climbed in traditional style; he free soloed like a madman. He did his own thing.

And then, just in case he had not already announced his presence with sufficient authority, Croft free soloed the North Face of the Rostrum, an 800-foot 5.11c route, a few days later. The ripple became a shock wave. Who the hell was this guy?

“Hey, Peter,” I said, jogging over to intercept Croft as he walked through Camp 4 one afternoon.

“Hey, Jeff,” he said. “How’s it going, eh?”

Croft was an anomaly on the climbing scene. He came across as something of a loner, which wasn’t so unusual, but he took it to extremes, as if he seemed to prefer at all times to be alone—even while climbing. Not so many years earlier, he had spent a season at Squamish, climbing every day and sleeping in a cave under a boulder. He was the pillar of the Squamish climbing community, universally liked and known for his sense of humor and entertaining stories. But in Camp 4, he didn’t seem to hang around with anybody. Sure, you’d see him talking with Bachar, Ron Kauk, or one or two of the other locals, but rarely with a group of any size. Still, he was not the least bit standoffish or intimidating. He was the equal of any Yosemite hardman, but also approachable. You could talk to him, even go climbing with him, and he didn’t treat you like you were nobody—even if you were.

Croft agreed to the interview, and we arranged to meet in El Cap Meadows the next morning. The following day, I hitched a ride out to the meadows and found Peter sitting on a log, gazing up at El Capitan.

“Are you ready?”

“Yeah,” he said, “but I need to make it quick. I’m going climbing.” Peter was unpretentious and taciturn. He said he loved to travel, to meet people, and to climb. He was genuinely humble; self-confident, sure, but not at all cocky. He didn’t think of himself as the best climber around, even if he probably was. He spoke of his climbs as if they were nothing special, even his hard free-solo climbs; they had been fun, an amazing adventure, but no great accomplishment. To hear him tell it, he thought every climb he ever did was the best climb he had ever done. He had an insatiable appetite for rock. It could be 5.8 or 5.12, he didn’t care as long as he could climb. Sitting for a forty-five-minute interview beneath the glowering visage of El Capitan must have been torture for him. He kept looking over his shoulder at the Big Stone.

I had one question in particular I was dying to ask him, a question a group of us climbers had hatched the previous winter while sitting around Dan Lepeska’s house drinking beer and staving off another cold, wet Seattle winter. We were speculating about this and that climber’s motivations and what they might do next, including Peter Croft and where all of his soloing was headed. I waited until near the end of the interview to spring it on him.

“You’ve soloed the Rostrum now,” I said, setting him up. “Do you think you will solo Astroman?”

It was a fair question. If Peter was willing to solo 5.11c thin crack routes like ROTC and the North Face of the Rostrum, why not Astroman? Todd and I had mulled over the possibility in camp, and thought it would be brilliant if he did it. It would be, we agreed, the next great leap forward in Yosemite free climbing, Todd’s pending efforts on The Stigma notwithstanding.

“No,” Peter answered. “It’s just too thin in some places.”

It was a lie: he would free solo Astroman two years later, then free solo both Astroman and the Rostrum in a single day, then climb the Nose and the Salathé Wall in a day, among a bunch of other incredible big wall link-ups and speed records. But for now, with his usual humility, he denied such aspirations. For Peter, it was all about getting into the flow and climbing, climbing, climbing. His message was clear: climb as much as you can for as long as you can and have a hell of a good time doing it.

Learn more | March 26, 6pm PDT

Arguments, fistfights, and even death threats were all part of this revolutionary time in rock climbing known as the “hangdog days”—and Jeff, an active climber of the era, was there to witness it all, right alongside superstars like John Bachar, Todd Skinner, Alan Watts, and more. Join us on March 26 for a deeper dive into this wild era. Plus, when you register to attend, you could win a free copy of Hangdog Days.

Jeff Smoot

Jeff Smoot