On behalf of The Mountaineers, I'd like to wish a Happy Birthday to one of our longest standing and most distinguished members: Wolf Bauer - pioneer, first-ascensionist, champion skier, sea kayak course and boat innovator, founder of Seattle Mountain Rescue Council, and esteemed conservationist.

We recently wrote about Wolf Bauer in the Retro Rewind section of our magazine. I'd like to share that featured article with you now.

Wolf Bauer

a true pioneer of the Pacific Northwest

by Mary Hsue, Director of Development & Communications

Upon joining The Mountaineers staff, Executive Director, Martinique Grigg handed me a book titled The Mountaineers: A History, published in 1998 by Mountaineers Books. She thought it would give me a good perspective on the impact and evolution of this hundred year old organization. A fascinating read and one I could not put down, the book provided that and so much more. Well before reading the last page of the book, I had developed a sense of pride for The Mountaineers and a deep appreciation for early members who played a huge role in the development of the outdoor industry, the establishment of national parks and wilderness areas, creating one of the first climbing courses in the nation, and founding the nation’s first Mountain Rescue Council. The book has become required reading for all staff members.

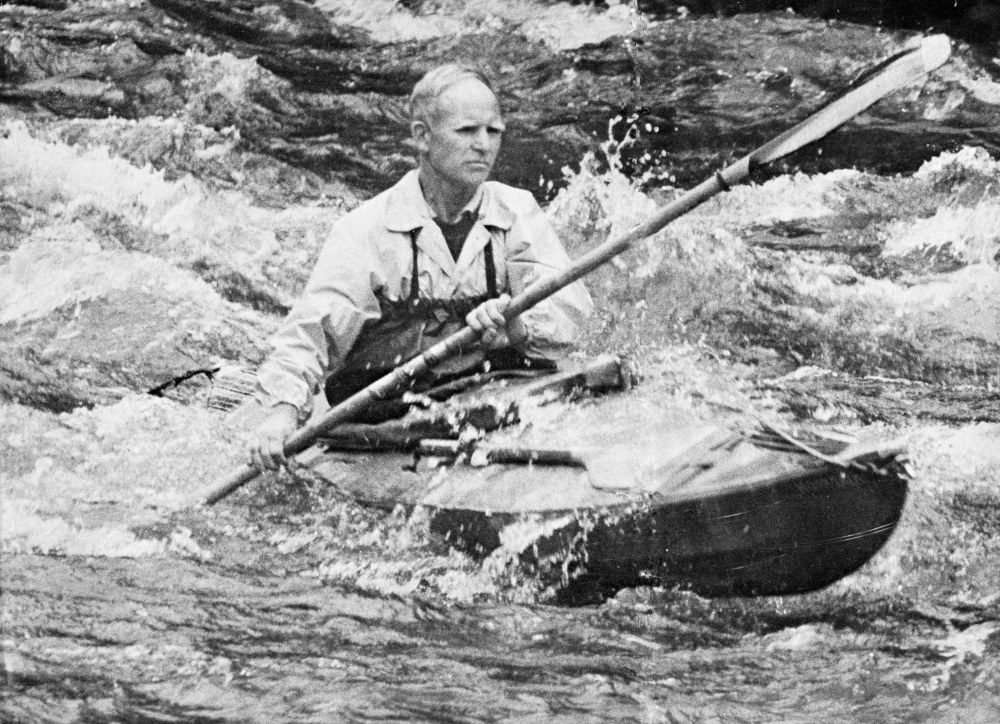

One name mentioned more than any in the book is Wolf Bauer. Bauer, who turned 102 this year, has been a pioneer all his life. In addition to helping start the climbing course and making a number of impressive first ascents, including the first ascent of the Ptarmigan Ridge on the north face of Mt. Rainier, Bauer was a champion skier, and in 1948 founded the Seattle Mountain Rescue Council. He not only created the first kayak club in the Northwest, his designs and innovations led to the development of the modern fiberglass kayak. His love of outdoor recreation fueled a desire to protect the natural landscape and led to his creation of the Washington Environmental Council.

In 2014, The Mountaineers recreated one of our organization’s grand traditions by holding, for the first time since 1941, the Patrol Race, an 18.5-mile backcountry ski race along the crest of the Cascades. From 1930 to 1941, three-man patrol teams competed in the race between The Mountaineers Snoqualmie Pass Lodge and Meany Ski Hut near Stampede Pass, a contest that The Seattle Times on December 10, 1944, called “one of the year’s great competitive events.”

The Mountaineers’ first Patrol Race of 1936 was only open to Mountaineers members. The racing teams had 18 miles of perfect powder snow, and the winning team of Wolf Bauer, Chet Higman, and Bill Miller set a new record time of 4 hours, 37 minutes, 23 seconds, which was destined to stand for many years to come. The 2014 Patrol Race was coordinated by Nigel Steere, whose grandparents were involved with The Mountaineers’ Meany Ski Hut in the early 1930s. The winning team consisted of Cody Lourie, Jed Yeiser, and Luke Shy, who finished in 7 hours, 9 minutes, beating the second-place team by 20 minutes.

“Meany Lodge welcomed them with cheers, awards, hearty dinner, and a warm night’s sleep after race temperatures and winds in the teens,” according to the official report of the race. Mountaineers officials sent the race results to Wolf Bauer, who was eager to learn whether his 78-year-old race record of 4 hours, 37 minutes had been broken: it had not.

An Unmatched Influence on Outdoor Recreation

Below is a story I chose a story from The Mountaineers: A History, that climbing course students and recent grads will enjoy – Bauer and handful of his students making the first ascent of Mount Goode.

“In 1936, Wolf Bauer led his first climbing course graduates on a venture he felt would test their skills. The group chose 9,200-foot Mount Goode, a fortress of a mountain at the head of Lake Chelan and one of the most sought-after first ascents in the Cascades. Herman Ulrichs had written of his attempt on Goode in the 1935 American Alpine Journal. Several parties of experienced club members representing the best in the Northwest had been thwarted by a particularly tricky chimney near the summit.

Among the graduates who accompanied Bauer were O. Phillip Dickert, Jack Hossack, Joe Halwax, and George MacGowan. All would go on to become familiar names in Northwest climbing.

Nothing looked very promising for this climb at the outset. The weather was wet and bleak. And on the ferry ride up Lake Chelan to the village of Stehekin, they discovered a pile of climbing equipment aboard and learned that it belonged to two Canadian climbers who were also attempting the first ascent of Goode, via the northeast side. But Bauer had the foresight to call ahead, and the local hostelry manager was waiting for them at Stehekin with a truck. They were whisked the sixteen miles up the Stehekin River to the trailhead as soon as the boat docked, giving them a head start.

Bauer was first to reach the narrow chimney just below the summit that had stopped so many climbers before him. MacGowan wrote of the climb in the 1936 annual: “The rear wall of the chimney sloped back at an angle of 50 to 75 degrees, and was covered with ice and snow. The side walls were also verglassed, making friction climbing impossible. Wolf worked his way up, driving pitons wherever possible, having considerable trouble making them hold in the ice-filled cracks… In due course the entire party arrived at the top of the chimney, which was about 150 up high and ended in an overhang.

“The right wall was vertical for 100 feet, and the left six or seven, slanting back to a ledge 30 feet higher. With some difficulty, Wolf stemmed up between the walls, here about five feet apart, crossed and scrambled to the ledge above, where he drove a piton, to belay the remainder of the party to his side. Here we thought our difficulties were over, as the ledge led to the left in a most promising manner, but on exploring we found it ran onto the face of the cliff and we were forced to return to our original position on the ledge.

30 feet higher, a break in the ridge looked like a probable solution to our difficulty, and while dubiously realizing that the first man would have very little protection, Wolf spied a crack in the granite ten feet above. The second flip of the rope caught, and ascending with prusik knots, he found himself on a narrow sloping slab with no close holds. With considerable effort he was able to drive a piton far enough to his right to protect himself until he worked over to where a finger traverse was possible.

“A few anxious moments and he was on the ridge announcing that the way was clear to the summit.”

At that point, Bauer and Hossack couldn’t resist a practical joke. They scrambled to the top and built a small cairn, then announced to the others that the boys from Canada had beaten them to the summit. The others were forlorn until they went looking for the summit register that would surely have been left behind and the joke was revealed. The Canadian climbers never made it.

Martinique Grigg

Martinique Grigg