In July 1996, I was a rock climber with very little experience in the mountains. I found myself in Glacier, having moved to Washington State from the relative flat-lands of the East Coast, where "it might be hot but at least it's humid." I was working for a small outdoor education program, and my new friend there suggested we go climb a technical peak in the North Cascades.

"Hmm, I don't know, how hard is it?" I asked, eager (but unable) to appear brave.

"It's only 5.5 or 5.6, it will be easy!" he said. I was leading much harder climbs at the crags at that point, so felt confident that I’d be up to the task.

So off we went to Marblemount, WA to pick up a permit to climb the classic West Ridge of Forbidden Peak.

Connie Lightner, mother of teenage climbing phenom Kai Lightner, is fond of saying, "Sometimes you win, and sometimes you learn." This Forbidden trip allowed us to win, and even more so, to learn.

Photo provided by Steve Smith.

Photo provided by Steve Smith.

Lesson One: Take responsibility for your own route selection and know what skills are required.

I completely trusted my partner and left it up to him to pick the route and make all the decisions. He must have assumed I was more experienced, and I didn't realize I was signing up for glacier travel, steep snow climbing, and an array of other alpine challenges. I had climbed a handful of multi-pitch routes at crags, but had absolutely zero experience mountaineering and had never set foot on a glacier before.

THE APPROACH

We got our permit and trudged up the steep, muddy trail, eventually arriving at Boston Basin, a stunning place full of wildflowers, marmots, and sweeping alpine panoramas.

We set up camp and went to pull out dinner. I had the MSR Whisperlite stove, and my buddy had carried a fuel bottle... but neither of us had the requisite fuel pump. We stared at our packages of pasta and put on a good face, but felt a sense of despair. How had we missed this crucial piece, and what did it mean for our larger ability to plan and coordinate our efforts? We scrounged snacks for dinner (one of us, who shall remain nameless, had actually brought an entire box of blueberry Pop Tarts) and headed to bed early for our alpine start.

Lesson Two: Plan, communicate, and double check what you’re bringing.

In this case, we managed to make it work, but really more through luck than skill. Had we forgotten a more essential item, we would have been in a much worse situation.

AN ALPINE START

We woke around 2am and enjoyed a few more cold Pop Tarts before setting off towards the looming ridgeline of the peak. As we traveled across the snowfield, it imperceptibly turned to glacier, which became quite convoluted as we approached the couloir commonly used to access the upper ridge. We did not discuss roping up on the glacier, and we proceeded by climbing unroped up the couloir.

It had been warm the night before, and it was easy to kick deep bucket steps as the couloir gently steepened. Soon, using two ice axes each and still climbing unroped, we were hundreds of feet above the glacier. I felt secure due to the snow conditions, although I was aware I had never actually practiced self-arrest before and was unsure what I would do if I were to slip.

Photo provided by Steve Smith.

Photo provided by Steve Smith.

Lesson Three: It’s easy for more experienced climbers to underestimate the difficulty of terrain for beginners.

I was basically testing and discovering my limits and abilities in terrain that would have been extremely unforgiving (or worse) had I failed. I didn’t have the experience to be soloing on the terrain where I found myself, and didn't know what I didn't know.

Climbing The WEST Ridge - Slowly

We made it onto the ridge crest, changed out of boots and crampons, and stashed equipment for the rock climb ahead. It was a warm, pleasant day on the ridge, with no other parties in sight. We roped up and started simul-climbing along the ridge-crest, a technique which was new to me but which intuitively made sense.

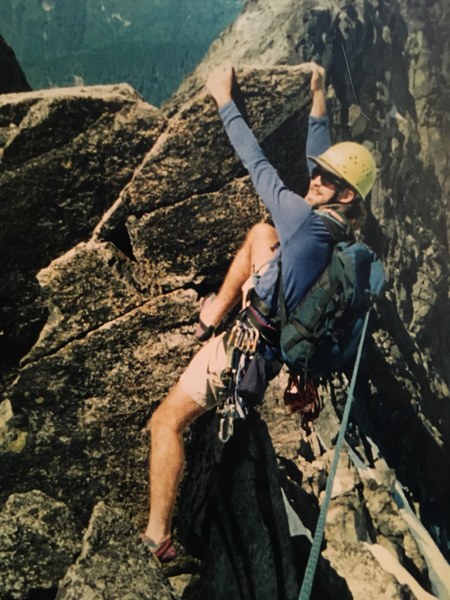

Photo provided by Steve Smith.

Photo provided by Steve Smith.

I found climbing pitches as the second climber much easier than being on lead, where I had to navigate the challenges of rope drag. I was more accustomed to crag climbing than ridge climbing, and the route wandered around gendarmes from one side of the ridge to the other. As I climbed, I placed gear in less-than opportune places in order to minimize rope drag. At times, it likely would’ve been better to belay than simul-climb – it would have been just as fast and without the added risks of a simul-climbing fall.

The day was lovely, and the remarkable views got better and better as we moved up the ridge.

At one point we were sitting together on the ridge, eating and drinking, and I took my rock shoes off to relieve some of the pain in my feet. A moment of drama – the equivalent of a near-miss, really – occurred when I decided to put my rock shoes back on again. As I tugged hard on the heel loop to pull my tight shoes back onto my foot, the heel loop slipped out of my hand, which led the shoe to catapult straight up into the air about fifteen feet, hovering delicately a thousand feet above the glacier, with me and my partner staring in disbelief as it trembled in the light breeze. Miraculously, it fell straight back down into my arms. My partner and I looked at each other; not a word was spoken. We'd left our boots way back at the top of the couloir, so all I had with me were my climbing shoes. Losing one would've been disastrous.

Another desperate situation, narrowly avoided solely by luck.

Photo provided by Steve Smith.

Photo provided by Steve Smith.

Lesson Four: Maintain situational awareness.

Through lack of awareness and carelessness, I almost created a dire scenario in a remote, precariously-exposed area. I was taking my shoes on and off on the ridge just like I was in the habit of doing at a roadside crag, with no situational awareness whatsoever to the potential consequences of my choices.

So upwards we continued. As the sun traversed across the sky and began to drop towards the western horizon, a harsh mid-summer glare began to soften to warm, golden colors. We made our way to the summit as the last golden rays of sun sank below the horizon. It was now starting to get dark, and we had been on the move continuously since 3am.

Abruptly, I realized there was no chance whatsoever that we'd be off this peak before nightfall.

Lesson Five: Establish a turnaround time and re-evaluate your progress as you go.

We were so focused on making the summit we didn't even consider assessing the time. I don't know how we wasted the entire day up there on the ridge, but I have lots of photos of us eating, drinking, and having fun – I think we were just enchanted. We should’ve set a turnaround time in advance, which may have given us a sense of urgency or at least helped us make a conscious choice about continuing or turning back.

THE DESCENT

With night nearly upon us, we began to race down the ridge. Due to the diagonal and traversing nature of the ridge, it was hard to move quickly. Rappels took us diagonally off the natural fall line, and down-leading subjected the follower to frightful exposure on the descent to the next piece of gear. Slowly, we inched our way down the ridge.

We found the first rappel anchor at the top of the couloir, and began the second rappel into the heart of the couloir as the last rays of sun sunk below the horizon. I volunteered to go first on the second rappel. I set off down the moderately steep snow into the couloir, my headlamp sweeping from left to right as I made my way downwards.

In mid-summer, the snow melts away from the rock walls on either side of the couloir, putting the rappel anchors farther and farther out of reach. As I descended, I noticed several rappel anchors 15-20 feet above the snow, separated by a deep, dark moat between the snow and rock. I reached the end of my rappel and strained against gravity to see if I could pendulum over to one of the anchors; then promptly blew out my footholds in the snow, falling backwards into the moat and landing upside down at the very end of rope.

In 1996, tying knots in the end of the ropes or using auto- blocks to back up rappels had not become a common practice. Without these safety measures, I was at risk of sliding off the end of the rope and into the deep abyss, between the ridge and the glacier.

Lesson Six: Use good habits and backup systems to manage the consequences of human errors.

Tying knots in the end of the rope on a rappel, especially at night when it's hard to see the next rappel station, can save your life. The fall into the moat could easily have dislodged my brake hand, causing me to slide off the end of rope with dire consequences.

Once we re-established ourselves in the couloir proper, we had hundreds of feet of relatively steep and exposed snow to descend. There's no way we could reach any of the rappel anchors on either side of the couloir, as the snow moat on either side was too big. We had no choice but to down-climb the steep, soft snow.

My headlamp died, and I was fairly certain I was next. In the moonlight, I could see the yawning bergschrund far below, and imagined myself sliding and tumbling down the mountain into that gaping hole. Somehow, step by step, we descended through the snow, climbing down into the bergschrund and back up the other side.

Once on the gentler snow slopes, we trudged down to the grassy meadows and eventually to our tent in the basin. We arrived around 2am, approximately 23 hours after we left. I promptly passed out.

By the time we awoke the next morning, the sun was high in the sky. On the hike out, I was so exhausted from the previous day that I face-planted on the only semi-flat section of trail between camp and car. Laying on the ground with my face in the talus, I considered my choices for an unusually long and humbling time.

How this experience affected me

Despite all the crises narrowly averted by sheer luck and the utter mental and physical exhaustion, I also gained experiences that would go on to define much of the rest of my life:

- A true sense of partnership and connection that only develops from overcoming risks and challenges through teamwork

- A desire to know these mountains better, to have a sense of place in this wild and austere sea of peaks and ridgelines

- Unexpected joy at the sense of being on the thin edge between glory and tragedy

Conclusion

After the trip, I spent the next 20+ years of my life engaged in mountaineering pursuits, not only as a past-time and a lifestyle, but in a variety of professional roles.

As my love affair with the North Cascades and climbing deepened, I returned to Forbidden Peak again and again, climbing all three of its primary ridges, including the Torment-Forbidden Traverse in a day.

Forbidden Peak remains true to its name, and has been the site of multiple accidents and countless epics over the years. Contrary to popular knowledge, and certainly contrary to the unprepared style in which I climbed it over 20 years ago, the mountain requires skills, judgment, and fitness. It is not a peak for beginners, even if it impelled me as a beginner to launch into a lifelong pursuit of mountaineering, with powerful opportunities for learning and personal growth along the way.

Photo provided by Steve Smith.

Photo provided by Steve Smith.

Steve Smith is a risk management consultant at Experiential Consulting, LLC, where he serves outdoor/experiential education programs. His career has included administrative leadership roles with national organizations including Outward Bound and The Student Conservation Association. As a member of The Mountaineers’ Adult Education staff, he helped envision and launch Progressive Climbing Education and Alpine Ambassadors. Learn more about Steve's work at outdoorrisk.com.

This article originally appeared in our Spring 2019 issue of Mountaineer Magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, click here.

Steve Smith

Steve Smith