We hear their songs in the morning and almost subliminally note their presence throughout the day. While some of us seek them out, watching for certain species that herald a new season or hoping to see unusual ones, others have a more passive awareness of these feathered wonders. Either way, birds are part of all of our lives.

The photographs and essays in Bringing Back the Birds are imbued with the idea that if birds, as well as other plants, animals, and natural habitats, are to be preserved, they must first be known and appreciated. They seek to inspire each of us to make a difference, to take small personal steps to create a bird-friendly environment where we can enjoy the magic of birds for generations to come.

Please enjoy the following excerpt from novelist, essayist, journalist, and birder Jonathan Franzen's foreword to Bringing Back the Birds.

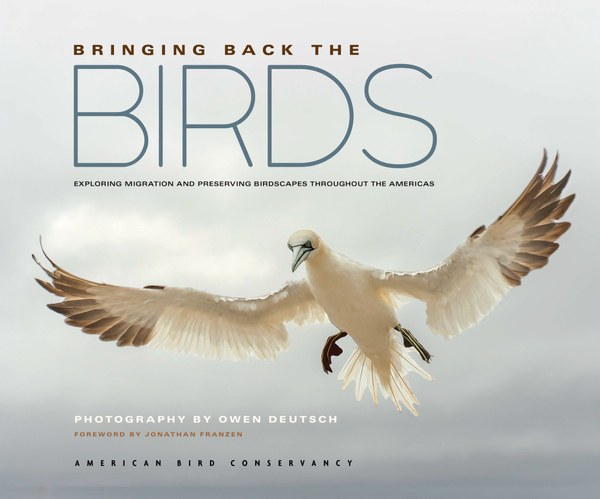

With a wingspan of more than five and a half feet, the Northern Gannet is the largest in its family, Sulidae, which includes gannets and boobies. Northern Gannets breed on rocky cliffs and islands on both sides of the Atlantic. Photo by Owen Deutsch.

With a wingspan of more than five and a half feet, the Northern Gannet is the largest in its family, Sulidae, which includes gannets and boobies. Northern Gannets breed on rocky cliffs and islands on both sides of the Atlantic. Photo by Owen Deutsch.

Bringing Back the Birds

The last time the earth experienced an extinction event like the one we’re facing in the coming century, the class of animals that survived to dominate the planet was Aves. When a meteor impact plunged the world into a catastrophic year-round winter, the avian branch of the dinosaur family tree had a number of advantages: full warm-bloodedness, accelerated embryological development, and sophisticated vocal communication. But no advantage mattered more than the ability to fly.

In the Western Hemisphere today, as in the Old World, the diversity and plenitude of birdlife is a testament to the power of flight. Over the ages, songbirds and hummingbirds have flown into every isolated niche in the Andes and evolved into new species; some Original Finch once rode the wind out to the Galapagos Islands, where its descendants began to specialize in different food sources, creating the minutely varied subfamily that Darwin studied.

Long-distance flight can speed speciation, and it can help a stable species thrive. The Townsend’s Warblers of California breed in insect-rich alpine forests and fly down to winter in coastal redwoods. Swainson’s Thrushes disperse across the interior of South America and then, in April, migrate as far north as Alaska, where they burst into hauntingly complex song. Hundreds of thousands of Sooty Shearwaters circle Monterey Bay in August, in formations so dense they look like sooty airborne rivers, before recrossing the Pacific Ocean to nest sites in New Zealand. The parrots of Bolivia are constantly in motion, fanning out in the morning in search of food, commuting to the clay licks that aid their digestion, and returning to roost at nightfall; they may spend their non-breeding season hundreds of miles away from where they nest. Almost all bird species migrate, or venture forth, or accidentally stray. Winged movement is birds’ essence and glory.

The striking Yellow-throated Warbler has several subspecies; some are nonmigratory, staying in the southern United States year-round. Migratory populations of this warbler are among the first birds to arrive back on the breeding grounds each spring. Photo by Owen Deutsch.

The striking Yellow-throated Warbler has several subspecies; some are nonmigratory, staying in the southern United States year-round. Migratory populations of this warbler are among the first birds to arrive back on the breeding grounds each spring. Photo by Owen Deutsch.

In the face of the next global extinction event, which is now threatened by human destruction of habitats and depletion of resources, and which is certain to be aggravated by the future increase in global temperatures and extreme weather events, airborne mobility does not confer the same advantage to birds that it did 65 million years ago. Seabirds can still fly immense distances in pursuit of food, but during their breeding season they’re tied to the islands where they raise their chicks; if these islands are overrun with introduced predators, or if the waters around them are overfished, or if the adults drown on fishing lines, the chicks will die.

Flight will also not avail the species dependent on a particular terrestrial habitat—undisturbed ocean beaches, Pacific Northwest old-growth forest, Atlantic rain forest in Brazil—if all suitable habitat is destroyed. And many North American migratory birds need multiple habitats to complete their life cycle. There may still be plenty of temperate hardwood forest for the Wood Thrush to nest in, but the Central American forests where it winters are vulnerable to clearing for agriculture; Mountain Plovers may do well on the American high plains in summer, only to go hungry in winter in Mexican grasslands that are overgrazed or converted to row crops. Nonmigratory tropical birds, which are less tolerant of temperature variation than temperate species are, will be sorely pressed as climate change heats up the Amazon basin and Central American lowlands.

And yet birds are the toughest of the tough. They’ve covered the earth’s surface for tens of millions of years, and their mobility will give many of them a fighting chance in the coming century. How well they do will depend, in large part, on our commitment to conserving them, and on the creativeness of our conservation solutions. For people who care about the natural world, it’s not enough to focus exclusively on climate change, which now can be only mitigated, not avoided. The most promising conservation projects today target large expanses of land and large groups of species, and are attuned to the needs of both wildlife and human beings.

The lovely Violet-tailed Sylph is found in the cloud forests and forest edges of Colombia and Ecuador. It’s named for the male’s long forked tail of shimmering violet tipped with blue. Males with longer tails dominate shorter-tailed competitors, even plucking feathers from their backs during squabbles. Photo by Owen Deutsch.

The lovely Violet-tailed Sylph is found in the cloud forests and forest edges of Colombia and Ecuador. It’s named for the male’s long forked tail of shimmering violet tipped with blue. Males with longer tails dominate shorter-tailed competitors, even plucking feathers from their backs during squabbles. Photo by Owen Deutsch.

Organizations such as Osa Conservation and the Área de Conservación de Guanacaste, in Costa Rica, and the Amazon Conservation Organization, in the Peruvian Amazon, are creating reserves whose great size and altitudinal gradients will protect tropical birds from the worst ravages of climate change, while improving the lives of local residents. Although seabird populations have declined calamitously in the past fifty years, they’re making a strong comeback on islands cleared of invasive predators by groups such as American Bird Conservancy (ABC), Island Conservation, and the South Georgia Heritage Trust. Sensible management of ocean fisheries will help them further, as will efforts by ABC and BirdLife’s Albatross Task Force to promote simple, inexpensive methods of reducing seabird deaths from fishing lines and nets.

In the grasslands of Chihuahua, ABC and its Mexican partner, Pronatura Noreste, have demonstrated that small investments in fencing and water tanks can enable local ranchers to remain on their land while providing much better habitat for wintering grassland birds: a win-win. The demonstration is one element of the ambitious program that ABC has launched to bolster the populations of entire suites of migratory birds, at both ends of their migratory journey. The program operates at the landscape level and seeks more win-wins—for both the Wood Thrush and the Central Americans who live where it winters, for both the Golden-winged Warbler and North American outdoors people.

Nature is not an abstraction. Its beauty, its hazards, and its utility are wonderfully and terribly concrete. To prevent its destruction in the twenty-first century, we need to roll up our sleeves. We need concrete approaches to specific challenges. For those of us who especially love the birds of the Western Hemisphere, there is no better group than ABC, which not only works to secure habitat for all American bird species but takes the lead in combating every direct systemic threat to them. Where there’s a will, and wings, there’s a way.

Read more in Bringing Back the Birds: Exploring Migration and Preserving Birdscapes Throughout the Americas, available now where books are sold. Featuring more than 225 stunning photographs from Owen Deutsch alongside essays from leading experts, including Peter P. Marra of the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, John W. Fitzpatrick of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, naturalists Kimberly and Kenn Kaufman, and more. 100% of royalties support American Bird Conservancy and the important work they do to bring back the birds.

Mountaineers Books

Mountaineers Books