by Joan E. Miller, Mountaineers Naturalist Writer

Resident orcas of the Salish Sea may be wild creatures, but satellite tags, drone images and individual health profiles are making them as familiar as family to researchers. The distinctively marked, largest members of the dolphin family that comprise the J, K, and L pods, also known as killer whales, are being studied inside and out. While scientists monitor the whales’ whereabouts, new babies, and what’s happening with food sources, they’re also analyzing the whales’ feces and blubber to better understand the health of individuals.

The three pods number 84 at the moment, though “it depends on when you count, “says Elizabeth Petras, a marine policy analyst with NOAA Fisheries, “It’s a dynamic population.” This orca population has had its ups and downs. Several births over the past year and a half have been good news, though at least one is believed to have died.

Orcas swim all the world’s oceans, with the global population estimated at 50,000. In the Pacific Northwest, they’re icons, deeply intertwined with natural and cultural history. Also known as blackfish among coastal tribes, they’re powerful and strong in legends. Killer whales are clan animals for the Tlingit, Tsimshian, and Kwakiutl tribes. Orcas are represented on totem poles and in native art. Various legends say that orcas are the transformed spirits of hunters or fishermen lost at sea, or of chiefs reincarnated, and that when whales are near shore, they are trying to communicate with their former families.

Killer whales have long called Puget Sound home, but compared to their historical numbers, the low number of individuals considered “resident” in our waters since the mid-1990s has raised alarms. What is happening and what sets our orcas apart from the rest?

The world’s orcas vary by type, based on their food choices. Transients eat marine mammals like seals and sea lions. But the J, K and L killer whale pods don’t live up to their vicious name, preferring to dine on Chinook salmon, the largest of the Pacific salmon. This can spell disaster as salmon can be scarce.

Combine picky eating with exposure to a soup of toxics and hazards from vessel traffic, and you have an orca population living on the edge. In 2005, the Southern Resident killer whales received protection under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), meaning the government was required to create a recovery plan, which it finalized in 2008.

The result of the listing is a flurry of studies being conducted by several partner organizations, including the Puget Sound Partnership and the San Juan Islands-based SeaDoc Society, which conducts research on marine life of the Salish Sea and provides veterinary services to marine mammals.

Among those analyzing data are Elizabeth Petras and Lynne Barre of NOAA Fisheries. Barre was the principal author of the recovery plan, which has a goal of restoring populations to the point where they no longer need ESA protection.

Locating the orcas in order to study them can be tricky. Though the J, K. and L pods spend much of their time between Puget Sound, the San Juans and Georgia Strait, K and L are known to head to coastal waters from southeast Alaska down to Monterey Bay, California, while J pod stays around inland waters. “We’ve had fewer sightings this year,” Elizabeth said of the southern residents in mid-summer. “We saw a lot more transients.” The theory is that southern residents leave inland waters in search of food.

Scientists are compiling data for the endangered whales into personal health profiles. Researchers use a range of methods to collect information about Salish Sea orcas. Biopsies have been taken from blubber of all individuals in the J, K, and L pods. Such samples have revealed many toxic residues, including DDT, which persists in the global environment. “If there are fewer salmon around,” explains Lynne, “they’re using their blubber stores, where the contaminants can be sequestered. But when they’re actively using that blubber, that’s when they circulate systemically and cause immune or reproductive problems.”

What health profile would be complete without a fecal sample? University of Washington researchers are using dogs trained to detect whale poop. Scientists go out in a boat with a dog, typically a Labrador retriever, who can sniff the water and detect whale feces on the surface. Then, the boat heads to the spot and researchers scoop it up. These outings take place in the San Juan Islands, notes Elizabeth, one of the most reliable places to find orcas. The dogs are part of Conservation Canines, a program of the Center for Conservation Biology at the university.

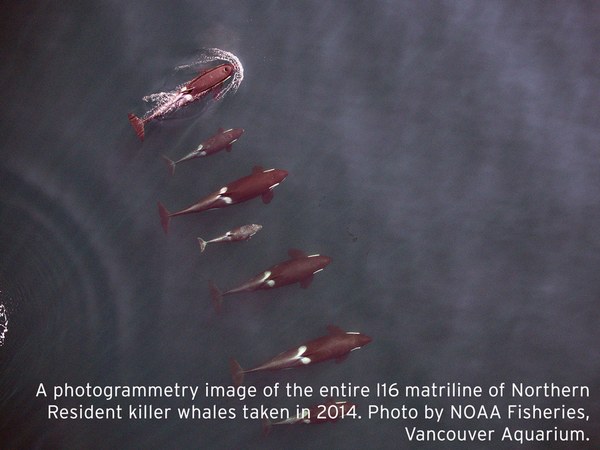

Drones are supplying aerial photographs that are revealing the condition of the whales, while keeping a safe distance that doesn’t disturb them. The NOAA team is excited about using this technology. “This can help us see when and where the whales might be food-limited and that will help me target recovery of key salmon stocks for the whales,” Lynne says. Scientists can also tell whether whales are thin, fat or looking pregnant.

All these efforts are yielding a clearer picture of how our orcas live and what they need to survive. There are simple things we can do to help protect orca habitat, says Elizabeth: conserve water, clean up after your pets, reduce pesticide use, reduce stormwater runoff, reduce auto emissions, and be aware of where your seafood comes from.

Orcas have made a journey through millions of years. With our help, they can continue to enrich our spirits for thousands more.

Add a comment

Log in to add comments.Thank you Joan Miller for this good article on our Salish Sea Orcas. As we go boating in the PNW it is important to keep an eye out, and practice safe boating and motoring habits, while sharing their waters. 👍

Joan Miller

Joan Miller