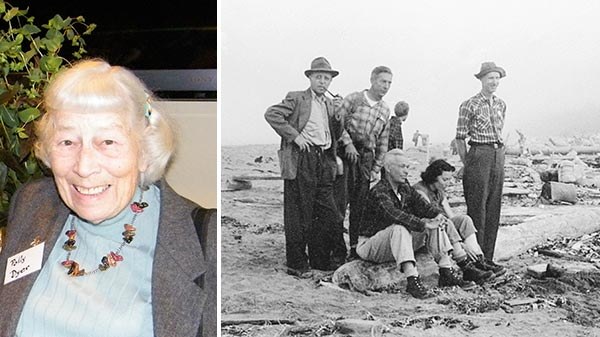

Today, if you go to Olympic National Park, you can head to the Valley of Rainforest Giants, where you’ll find some of the oldest, largest trees in the world. Among them stands the legacy of another giant: Polly Dyer, a long-time Mountaineers member and conservation visionary, integral to protecting wild places on the Olympic Peninsula and throughout the Pacific Northwest.

On Sunday, November 20, Dyer passed away at 96. Hers was a life filled with wild wonder for the outdoors, a passion that carried her from childhood walks through the dunes of Lake Superior to Congressional hearings, Governor’s meetings, and the forefront of the conservation movement.

She moved to Washington in 1950 – a time when the state’s wild places were largely up for grabs. As author Christian Martin writes in his book The North Cascades: Finding Beauty and Renewal in the Wild Nearby (published by Mountaineers Books):

“Without Dyer and her ilk, imagine what might have been: Clear-cuts in the Stehekin Valley. A half-mile-wide open-pit copper mine in the shadow of Glacier Peak. The ancient cedars of the Little Beaver Valley drowned underwater. And elsewhere in the state, a ski area, tramway, and golf course on Mount Rainier; the Hoh River valley excised from Olympic National Park and sold for timber. Instead of the most primitive stretch of coastline in the Lower-48, a scenic highway running along the beaches from La Push to Shi Shi.”

Dyer’s conservation work began in 1953 in response to Governor Langlie’s efforts to open Olympic National Park up to logging. The claims were to be approved by the Olympic National Park Review Committee, a panel stacked with timber interests. The Mountaineers objected, writing a letter to the governor. In response, he appointed five more people to the committee, including the president of The Mountaineers. However, since the president was unable to attend meetings due to his work schedule, Dyer took the helm.

In Dyer’s words, “By default I became a member of the committee. That was a major education… I learned to speak out. I used to be considered shy, but no more.”

The Mountaineers organized a letter-writing campaign, submitting more than 300 letters. In the end, Dyer’s leadership and The Mountaineers’ advocacy proved pivotal in preserving Olympic National Park.

This victory marked the beginning of Dyer’s lifelong commitment to protecting wild places. Leading up to the Wilderness Act of 1964, she testified before the US senate, describing nature as a, “…priceless asset which all the dollars man can accumulate will not buy back.”

Her words ultimately made it into the final legislation. She and fellow conservation Howard Zahniser are credited with defining wilderness as: “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” In particular, the word “untrammeled” is rooted in Dyer’s prior description of the Olympic Peninsula.

Her leadership was all the more impressive given the political climate of times. She recalls,

“I’d go to those forestry meetings and when I think back on it, I might have been the only woman in the room unless there was a secretary, but I didn’t hesitate to get up and ask a question.”

As fellow Mountaineer and lifelong conservationist, Helen Engle reflects, “Women from The Mountaineers were right there because they had tramped those trails and been in those places. And they knew the boundaries and what was encroaching on those boundaries.”

Today the US boasts 765 designated wilderness areas, totaling 109,129,657 acres of land – all defined as “untrammeled.” Dyer – who went into her first meeting with Governor Langlie in 1953 as a self-described “footloose and fancy-free housewife...” – answered the call and went on to literally define wilderness in our nation.

Now, more than ever, we all must answer the call to protect our public lands. Tom O’Keefe of American Whitewater echos this as he remembers Dyer:

“I'll miss Polly. A couple years ago I was with her and she pulled out her copy of the Elwha River Ecosystem Environmental Impact Statement and handed it to me. With a twinkle in her eye she said, ‘This is for you; thanks for all you do.’ The subtle gesture was recognition that the next generation would be carrying on her work. It will take a whole team of us to carry on her legacy.”

Katherine Hollis, Conservation Director at The Mountaineers affirms, “Polly is not just part of our organization’s history; she’s part of our future. As we continue to protect our public lands, we do so with Polly’s vision guiding the way.”

Add a comment

Log in to add comments.I had the pleasure to work with Polly on the Conservation Committee in the '90's discussing issues and getting out info to the membership.

Other then learning climbing techniques in the Mountaineers i think I learned more about working on a committee that had a great impact on life in the NW.

And Polly was a person that has influenced my Mountaineer experience.

The Mountaineers

The Mountaineers