by Scott Braswell, Mountaineers Climb Leader

On June 20th of 2015, a team of six Everett Mountaineers set out for Dome Peak — a remote glacier climb in the Darrington Ranger District. Dome is prominent along the Cascade Crest, one of the Bulgers, and a full 3-day trip brimming with interesting terrain. The Mountaineers website describes it as a “challenging” trip, rates it a “strenuous 5/5,” and points out that, “fitness for long days is essential.” So basically we had signed on for a suffer-fest.

And Dome Peak delivered. I had calculated the first day approach would be about 14 hours and over 5000 feet of gain, but a gnarly bushwhack up Bachelor Creek tacked-on time as we lost, back-tracked, and rediscovered the trail many times.

Josh, Grant, and Chelise, our wide-eyed students, were high-spirited and eager to please but the pace slowed and breaks grew longer as we gained elevation the first day. It was approaching dinnertime when our trip leader, Mark Baldwin, suggested we camp at Cub Lake rather than push forward another hour-and-a-half to Iswoot Pass. The Iswoot camp had been our goal because it would afford a view eastward across the basin at Dome Peak and would shorten the summit attempt by more than two hours. At that point we were all happy with the day’s efforts however, and satisfied with the more spacious camp we found in the crotch of Cub Lake.

Summit day began shortly before daybreak at 4:30am. Our new projection was 15 hours camp-to-camp. Even with the generous 16 hours of daylight this made for a snug timeline. We crossed the meadow in the early morning light and climbed the ridge to Iswoot Pass. There were a couple of tents pitched on the ridge. The packs and boots outside indicated that these folks were sleeping in. We discretely filled water bottles and snapped photos of our objective before descending into the talus field beyond.

We traversed the rocky basin at 6000 feet passing beneath two cleavers — tall rock outcroppings that barred any higher passage. Melt-water from the snowfields above funneled down through the rocks occasionally surfacing as small streams that we crossed gingerly, balancing on the slick wet stones.

From the second cleaver we lost our line-of-site to the peak behind a steep snowfield, but the route was apparent: climb the snow about 1500 feet and enter Dome Glacier high above the ice falls.

It was a bluebird morning and sweat trickled into my eyes as I frenched my crampons up the slope. At the top, the angle lessened and we regrouped to make our transition to roped travel on the glacier. Grant and Chelise were happy to drop the ropes from their packs and tie-in. Colleen and I each led a rope-team and Mark took a position at the tail of the second rope. We offered some final advice to the students. In summary, "Don’t Fall!" Then filed out onto the glacier.

Being a low-snow year there was little to conceal hazards. A denuded glacier is not much of a puzzle, so we kept a brisk pace as we maneuvered our ropes up-slope and around concavities. We skirted the open crevasses and only briefly jabbed at the glacier before stepping across finger-sized cracks in the ice.

We were all standing in the Dome-Chickamin Col by 11:30am. The col is a low point on the ridge separating two glacial cirques. There was another tent pitched here at 8,500 feet but it was unclear if the occupants were still around. The summit was within reach and our team was feeling good. We crossed over to the east side of the summit ridge and followed the snow to where it dropped away from a rocky knife-edge which leads to South Peak, the true summit of Dome.

There was a sheltered ledge of snow against the rock where we un-roped and settled in for lunch. The view was spectacular; in every direction mountains fell away from us in grey-blue waves. On the furthest end of the ridge where the snow diverged from the rock, Colleen and Mark started building the anchor for a hand-line that would eventually run along the knife-edge and allow a more secure passage across the exposed rock to South Peak.

As they tested the rock and placed pieces, two climbers came up the ridge in our boot track. They visited with us briefly; it was their tent that we’d passed at the col below. They left the col a while after we passed by and made quick work of the 300 feet climb to the summit ridge. Their visit was brief and didn’t include the exposed scramble to South Peak. I thought it was peculiar that they would camp so close to the summit and not even top-out, but on the way down I found out why they were eager to move on.

Descent and Rescue

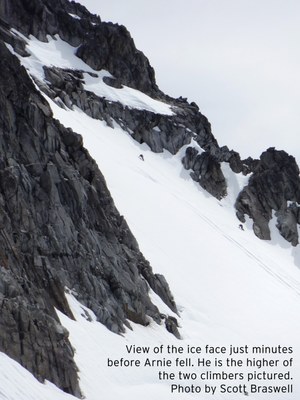

After the summit, we retraced our path along the ridge and down to the col. From the col we headed down the snow slope toward the glacier again. Most of Dome Glacier is a low-angle snow slope. The route we took across didn’t exceed 25 degrees of incline. In contrast, the west face of Dome Peak rises 800 feet above Dome Glacier at an angle of 45-55 degrees. It's steep enough that it avalanches regularly throughout the winter and spring, releasing the loose snow and leaving a firm scoured slope of névé snow that tapers to a thin crust near the summit. It was on the west face that we spotted two ice climbers free soloing above us. It turned out, they were the same two climbers we had met on the summit ridge.

In the zone where the low-angle glacier meets the steep snow face of Dome Peak a modest bergschrund has developed. The glacier is slowly slipping down the cirque and has broken away from the steeper snow face leaving a series of parallel crevasses along the bottom of the face. They’re not incredibly wide, generally not more than 4’ across, but they're frighteningly deep.

We marveled at the two ice climbers, their small dark figures mere specks on the snow 600 feet above. Are they roped? No, they were both moving up, slowly, toward the rock band below the summit. A rope between them would only ensure that if one person fell the other would also come off. A rope would only add security if one climber was anchored into the ice, belaying the leader up from a protected position. These two were free soloing the route, with no protection beyond the skillful placement of their crampons and tools.

I holstered my camera and turned my attention back to the glacier for a second, but then heard shouting. I looked to the west face. The top climber was sliding down, accelerating, his ice axe hissing and spraying as it split the snow. It was hard to judge the time or distance he fell. He struggled to arrest for a few long seconds before he lost control; caught a crampon and started tumbling down the face. Mark shouted, “Prepare to rescue!” We all stood transfixed. I carefully tracked him as he tumbled toward the bergschrund, watching closely to see where he would stop.

He hit the ‘schrund with a sickening thud and disappeared. It was the highest of three staggered crevasses in his fall line. "Go! Go! Go!" Mark yelled. My rope-team was 50 yards below the crevasse. Colleen’s rope was on the same elevation and while they traversed the slope to the north-end of the crevasse, my team crossed under and climbed up the snow to the south-end.

“We have to get there, NOW!” Mark hollered again. I encouraged Chelise and Grant to stay calm and move carefully, but quickly. I dreaded reaching him. He had fallen so far and fast, and the sound when he hit the ice; surely this was a body recovery. We traversed the snow above the lowest crevasse. “Belay every step. Take your time and get a good footing before you move the ax,” I coached my team.

Mark and Colleen reached the crevasse first. From our higher position I could see they were with the fallen climber. He was on a ledge inside the crevasse just a foot below the surface. Luckily, he hadn’t been swallowed-up in the deep ice.

We couldn’t reach him from the south-end, so Grant reversed the rope and crossed back under and around to the north-end. Josh had found a safe position just below and left of the climber. Mark and Colleen were up above. Josh had a stunned look on his face. I think we all did.

Mark and Colleen were tending to the victim. He was awake and alert, but in a lot of pain. It was Arnie, one of the climbers we’d met briefly on the summit ridge. His partner Amanda was still on the ice route high above. She called down to us, eager to know how he was doing.

“Are you anchored? Are you safe?” Mark called up to her. Yes, she was anchored, but she just saw her partner fall from above her and plummet past, 600’ into a crevasse. She was too afraid to climb any further. “Do you have a P-L-B?” Mark shouted to her. Between painful groans, Arnie informed him that she was carrying a Personal Locater Beacon.

“Yes.”

“Activate your P-L-B,” Mark instructed her.

“Okay!”

It was a relief to know that we could call for help, but we didn’t know how long Search and Rescue would take to respond or if they even received the SOS. We went through our packs and passed insulating pads and jackets up to Colleen. At first Arnie didn’t want them, he was still hot from the effort of climbing, but after a while he got chilled and started to shiver.

Grant and Chelise stomped a level platform in the snow and started melting snow on the emergency stove to make a hot water bottle. In his mind, Mark was playing out the possible scenarios. What if SAR didn’t come? What if they couldn’t reach us until tomorrow?

Arnie was perched on a ledge just inside the highest of three crevasses. He had severe chest pain and a thigh laceration from his crampons. As they tended to him, Colleen and Mark had to take care to watch their own footing and belay their movements with an ax. Another crevasse gaped at them from below, ready to swallow up any misplaced gear or either of them. We had to move this operation to safer terrain.

“I can go up to the col and bring their gear back down,” Grant offered.

Mark agreed, ‘Get everything useful you can carry; tent, sleeping bag, insulation… We can pitch the tent down there,’ he pointed to a broad flat area on the glacier a couple hundred feet distant.

He instructed me to build a snow anchor on the same level as Arnie and directly above a small snow bridge that crossed the lower crevasse. I collected the pickets and climbed up 15 feet to where Arnie was perched. About 25 feet left of him I planted a vertical picket and tied into it. Then I buried two deadman anchors, equalized them, and planted another vertical picket so that it would share the load. When it was all done my hands were purple and stinging from the cold. It took me four tries to tie a Munter hitch into Arnie’s rope, which they had readied.

I clipped into the completed anchor system and carved a seat into the snow beside it with my adz; that gave me a solid stance from which to belay. Mark tied into the other end of the rope with Arnie to help slide him along and give him support.

At some point during the preparations Amanda started to down climb. Arnie asked us, “Does anyone have cell reception?” We hadn’t checked, maybe it was an oversight but it was certainly a long-shot. A lot of ideas were getting thrown around and we prioritized things that were more likely to work. Colleen pulled out her phone. Her GPS app had been a godsend on the bushwhacking approach. Could she also get an emergency call out? It was worth a shot.

Arnie was able to move some under his own power. He groaned and guarded his ribs, but at least with him in control the pain was self-inflicted. I would have felt worse if we had to pull him around by his climbing harness. Mark planted an ice ax within easy reach and Arnie used it to pull himself forward a few inches. Then while he recovered, I took in the slack rope and Mark replanted the ax a few inches further. Each of us found a rhythm. Ax, crawl, rope, recover, repeat.

Progress was slow, but Arnie was inching his way toward me. At the same time, and at a similar pace, Amanda was inching her way down the west face. The sun was intense and reflecting off the snow like a solar oven. I lowered a bight of rope to Josh and asked him to clip a water bottle to it. I was parched.

It took about a half hour for Arnie and Mark to cover the 25 feet that separated us. About then we saw Grant plunge-stepping down from the col with a full pack on his back. Josh and Chelise scrambled down to meet him on the flat and set up the tent.

Now at the anchor, it was time for Arnie to change direction and head downhill toward the flats. This meant he had to trust my anchor. He looked down at the lower crevasse. It was wider than the one he’d fallen in and from our angle above it we could see a slot of the deep blue interior. He looked up again and asked, "did you use two pickets?" I held up three fingers even though there were actually four counting my first picket. “Bomber,” he said nodding approval. "How is Amanda doing?"

"She’s coming down slowly," I told him.

With this encouragement he shifted his weight to the anchor. I fed rope to him through the Munter hitch, slowly at first, and Arnie crawled backward down the slope letting gravity do most of the work. It was still very painful but he was gutting it out.

The angle mellowed as they got further down. They reached a point where it was easier for Arnie to stand upright and walk backward down the slope, then he was able to move a little faster.

“Half rope!” I called down. The tent was just 50 feet further and they had plenty of rope to reach level-ish ground.

At this point, everyone else was down on the flat. They prepped the tent with insulating pads and a warm bag and then maneuvered Arnie inside. I cleaned the ropes and anchor, then made my way down as well.

Amanda was still down-climbing when we first heard the powerful thumping of a helicopter rotor echoing off the valley walls. It was both exhilarating and a relief. “Where is it? Does anybody see it?” It was impossible to tell what direction the sound was coming from. For 15 minutes or more we heard the chopper get louder then fade away with our heads turned to the sky. It had to be close, we speculated. It was so loud!

When Snowhawk crossed over the ridge and we heard the full volume of its beating rotor, I felt such elation! They made a couple passes over us, circling the basin as we waved our arms furiously, then stopped at very near our eye-level but 100 yards down the glacier. The chopper hovered for half a minute then inexplicably peeled off and headed back down the valley. We were certain they’d seen us – they circled overhead at least twice and hovered for 30 seconds in plain view of us before turning around. Could they not land on the glacier? Did they need more personnel?

Fortunately, the Snowhawk didn’t leave our sight. We continued to watch, as they set down briefly on a low-lying ridge at the foot of the valley then lifted-off again and flew back in our direction. They returned to their earlier hovering position, but this time the chopper sank lower, and lower, until it nearly touched down. A tall man in an orange flight suit and white helmet climbed out onto the skid and hopped three feet down onto the snow. He took a litter from the doorway and was followed by a second medic in a navy flight suit with curly dark hair. The helicopter lifted off again and headed back down the valley. The men started up the glacier kicking steps with their boots.

Excited greetings were exchanged when they reached us. Mark briefed them as they walked together toward the tent to check on the patient. The two tall men crammed themselves halfway into the tent to check Arnie out. After the assessment and more discussion, the curly-haired medic slipped out of the tent to radio the helicopter crew. They were going to lift Arnie up to the helicopter in the litter.

Dave, the orange suited medic, called some of us over to help slide Arnie into the litter. Then we turned him feet facing down hill and blocked the litter with our boots to keep him from sliding away. “Can you wait for Amanda?” Arnie asked him.

She was getting close to the bottom and seemed to be out of danger, but was still 15 minutes away. “It’s too much weight! She’ll have to hike out with these guys,” Dave said patting me on the shoulder.

The helicopter returned. The pounding rotor wash nearly blew away the empty tent despite the ice axes staking 3 corners, so Grant jumped inside to weigh it down. It had been a warm afternoon on the glacier but now I was freezing, the cold air cutting through my jacket like it was gossamer. The cable came down from the helicopter. It wavered a little, just out of Dave’s reach then swung gently into his outstretched hand. When he had the carabiners all hooked up, he shouted to me over the maelstrom. “When I signal them, you just let go and get to the side. He’s going to takeoff that way.” He pointed down hill emphatically.

“Okay!”

He signaled the chopper but I had my head down over the litter, shrinking away from the cold. The litter started to swing away and I scrambled to the side as Dave had instructed. He had also tied a bright cord to the litter. As it went up to the chopper, the cord unspooled. He kept some tension on the line and helped orient Arnie as he came along side the door. Then Arnie was pulled inside.

I was relieved to be out of the rotor wash and we were all relieved to have Arnie in good hands. We collected as much loose gear as we could fit into his pack and Dave clipped it to his harness. After a few idle minutes, casting glances alternately at Amanda – still down climbing – and the helicopter, the cable came down again. Dave spooled up the slack cord as it came. He pulled the cable over, secured himself, then rode it up to the door as Snowhawk turned back down the valley.

We all breathed a sigh of relief and watched the chopper float away. The sun was getting pretty low in the sky. It was 6:30pm and we were still several hours away from our camp. We packed up the tent and organized ourselves into two rope teams. Amanda made it back to the glacier and joined us we got ready to leave. She was glad to be down and very appreciative of the help. It could have been so much worse.

We double-timed it back down the glacier following our ascent track. Shadows were getting long and we needed to move fast to get off the glacier before dark. Fortunately we did. I snapped a few more photos before the sun went down. Some of us still had enough energy to manage a bit of a smile. Mostly we were quiet, exhausted, and still a bit in disbelief.

The scramble down from Iswoot Pass was done in the pitch dark. It was hazardous in places, but Grant, Amanda, and I were able to scout a decent route down to the good trail on the meadow floor and guided the others around the worst of it. We got back to Cub Lake after 11pm. A group of us made dinner and recounted the events of the day in hushed tones. We had summited our peak, executed a smooth rescue and made it back to camp safe. All in a day's work for a Mountaineer.

Add a comment

Log in to add comments.What a fine tale of cascading competence, co-operation and care.

Well done Scott and team!

Scott Braswell

Scott Braswell