On the blue-skied morning of August 9, 1974, I steer our 1969 Ford van, “Bessie,” into the parking lot at Paradise. With me are my 16-year-old daughter Kim, my 14-year-old son Harold, and our fellow Mountaineer, 16-year-old Ken Cook. The four of us have completed all but one of our required climbs for Seattle’s Basic Climbing Course, and we’ve chosen Mt. Rainier as our graduation goal — a mountain none of us has summited before.

Standing in the parking lot, we fiddle with our packs in anticipation. From our vantage, we can see the hut at Camp Muir, our resting stop for the night. We meticulously rearrange our gear one last time, wave goodbye to Bessie, and hit the trail.

Making our way up the mountain, I ponder the risk of taking my teenagers and their friend on this serious climb. Although summiting Rainier is not uncommon, the mountain offers its share of hazards. Then I remember all the effort Kim and Harold have put into this course, preparing themselves for exactly this achievement. The decision to continue is obvious — but, being Dad, I watch them for signs of hesitation. They are steady as rocks.

Entering crevasse country

The arrival to Camp Muir comes fairly easily. With the first part of our journey complete, we rest our feet and indulge in a deluxe dinner of freeze-dried food. The climbers’ hut is crowded and noisy, but we find places to bunk before starting the climb.

It’s hard to unwind in our sleeping bags with all the commotion from climbers coming and going, but eventually we fall asleep. In what feels like minutes later, we awake to start the climb. Under a starry midnight sky, we set out across the Cowlitz glacier.

Anticipating a slower pace, Kim and I share our own rope. Leading Harold and Ken’s rope is a 17-year-old we picked up at Muir who reassured us he’d climbed the mountain a couple of times recently. I know it’s a risk to allow a stranger to join our group, so I watch him carefully.

We cross Cowlitz — the first glacier traverse — quite readily, which leads us toward a ridge-crossing known as Cadaver Gap, named after two men who lost their lives there in 1929. Thank God we had no such calamity. Lethal events on Mt. Rainier happen, but are rare considering the thousands who summit every year.

To avoid the fate of the 1929 climbers, we take the safer crossing of the ridge at Cathedral Gap and arrive at Ingraham Flats. We climb Ingraham Glacier slowly, paralleling the ridge for a while and then shooting across the glacier to stay above a yawning crevasse lined by flags planted by earlier climbers. A giant ice shelf hangs above our path, so we stay quiet, careful that our voices don’t cause disturbance. It’s a climbing motto to remain quiet while in dangerous areas. If the ice shelf above were to break, it would drag us straight into the large crevasse we are paralleling.

Kim's head peeking over a mound on Ingraham Glacier.

Kim's head peeking over a mound on Ingraham Glacier.

Fortunately, our crossing of Ingraham is safe, but that is not always the case. In a few years from now, ten novice climbers and one guide would follow our same route and be swept into the crevasse by an immense avalanche of ice and snow. When a climber is swept into a crevasse like the one at Ingraham, there is not much hope for their survival.

It takes two

As we approach Disappointment Clever, the sun begins to illuminate Little Tahoma in a most beautiful way. We take a short break to enjoy the sunrise show.

Beside us we hear the heated chatter of two young men. They are arguing about whether they should continue, knowing that eventually one of them will have to give way. On Mt. Rainier, it is extremely unsafe to travel alone. Whether you’re continuing upward or resigning to descent, the choice is a partnered package.

Harold and his team move on, but Kim continues to listen. I decide to gently check in with her, wondering if the strangers’ disagreement is making her question our climb. “Are you ready, Honey?” I ask. The two of us are a team, and where my daughter goes, I will follow. Her reply is earnest. “Yes, Dad. Let’s go.”

We continue up the Emmons Glacier. In the distance, we can see the boys charging up the mountainside, already halfway up. At 12,600 feet with the summit in sight, we see a big climber running from our right. He is perhaps a half-mile away, shouting, “Ho, there! Ho, there!” to someone, but we can’t tell who he’s calling. We keep on moving, because time is moving on.

It isn’t until after we get back from the climb that we’d learn the man was responding to a three-person climbing team that had fallen into a crevasse nearby. One member of the party got their crampon caught on their gaiter while crossing a snow bridge and slipped, dragging the two others with them; the other two went into self-arrest and lowered their companion to an ice shelf. No one died, but one member of the party fell into the crevasse and suffered serious injuries. In the mountains, a simple misstep can have serious consequences.

Reaching 13,900 feet, we encounter another couple arguing beside a large, frozen skating pond at 30 degrees. They’re also disagreeing about whether to continue, and their dilemma is the same — someone has to give. Regardless of what direction you’re traveling, you can’t go alone on this mountain.

Even so, I’m shocked they are having this argument with the summit rim in sight. I’m grateful that Kim is just as eager as I am to get to the top.

Reaching Rainier’s summit

Unperturbed by the arguing couple, we move forward, belaying one another over the frozen surface. One of us plunges our ice axe into the ice, digs our crampon front cleats in, and waits for the other to pendulum up. Gradually, we arc our way up the 30-degree slope. I know Kim is strong, and am confident she’ll hold me if I slip. Her trust in me is the same.

Finally, we make it to the top.

A view of Mount St. Helens before it erupted.

A view of Mount St. Helens before it erupted.

Our boys are exhausted, cold, and eager to descend the mountain, but they stay for a moment, allowing Kim her summit glory while I dig around for the summit register to sign us all in. I walk into the bowl of the summit crater toward Columbia Crest, the highest peak on Mt. Rainier at 14,410 feet. The horizon is endless with snow-capped Cascades. I take pictures in all directions, which pale in comparison to the in-person view. Among my snapshots is a view of Mt. St. Helens, about six years before it blew.

The boys begin their descent for Camp Muir, but Kim and I linger. We are in no hurry to leave.

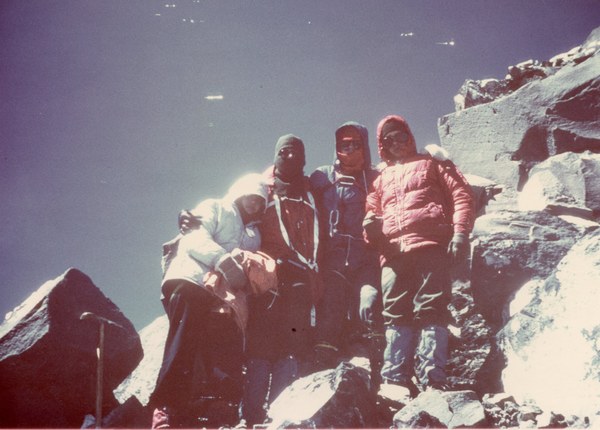

(From left to right) Kim, John, Ken, and Harold huddling for a summit photo.

(From left to right) Kim, John, Ken, and Harold huddling for a summit photo.

This article originally appeared in our summer 2023 issue of Mountaineer magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, visit our magazine archive.

Add a comment

Log in to add comments.This place is really beautiful i love this kind of places.

John Kutz

John Kutz