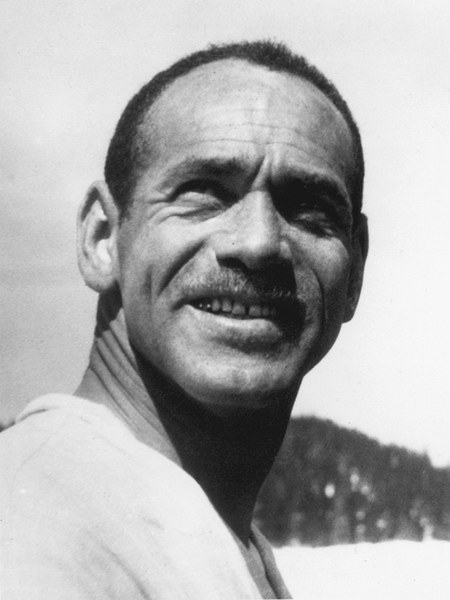

Charles “Charlie” Crenchaw was a member of The Mountaineers and the first African American to summit Denali. He did so on a Mountaineers expedition and Charlie wrote a report of the adventure for our 1965 Annual to commemorate the trip. The expedition, was exemplary for a variety of reasons, and Charlie’s recap has its fair share of excitement.

The trip resulted in a variety of firsts for the time, and James Edward Mills wrote about the expedition in his book The Adventure Gap [published by Mountaineers Books]. He wrote of the days following the adventure: “In all accounts of the expedition, Crenchaw was an equal and well-supported member of the team. The fact that he was black appeared to be wholly irrelevant. His race is mentioned only once at the end among the list of the team's accomplishments. 'The First Negro to climb Mt. McKinley — Charles Crenchaw' is included with the same weight and bearing as 'The largest number of women to reach the summit — three in one party' or 'the largest number of husband-wife teams — 2.' These details were recorded for posterity like baseball statistics, worthy of note but hardly a Jackie Robinson moment. Like so many achievements in climbing, the fact of its having occurred would be recognized and celebrated only by those to whom such things truly mattered. Crenchaw, like most climbers, upon his return probably took a day or two off from work before heading back to his job at Boeing with a few new water cooler stories and snapshots.”

Read on to see how it went in Charlie’s own words. (Note: Mount McKinley was officially renamed Denali, based on the Koyukon name “Deenaalee”, meaning “the high one”, in 2015. Charlie’s expedition took place 10 years before the name of North America’s highest peak became a subject of dispute. We have kept his original wording throughout this piece.)

-Trevor Dickie, Content Associate

On June 13 and on June 14 [1965] took the train for McKinley Park where we caught our first glimpse of Mt. McKinley. As we approached the mountain we were all looking out the window at what would be the altitude of Mt. Rainier and saw nothing. Then suddenly all heads raised, as if on a common lever, 6,000 feet higher; there in the distance stood the top of Denali. No jokes were made, we just quietly settled back in awe. It was huge - most huge! We understood why the Indians named it Denali - The Great One.

For three days, bent under 80- to 90-pound packs, we trekked across tundra, rivers, and glacial moraine, finally arriving at McGonagall Pass (5,600 feet). This was to be the site of the first air drop.

Camp II was established at Gunsight Pass (6,500 feet). Here we were confronted with our first major obstacle — the lower ice falls, which were crisscrossed with crevasses. One climber said of the ice falls, "It looked as if the gods had been playing tick-tack-toe with ice blocks." The break-up was horrendous.

Our first victim, Pat Chamay, fell into a crevasse on this trip; we rapidly learned that the Muldrow Glacier was very porous, shell-like, and always groaning. Crevasses were frequently opening, making any deviation from the established route hazardous. We moved up to Camp IIIA. Again foul weather chained us to the mountain, and we sat for two days waiting for the second, and vital, air drop.

On the mountain, time is precious, and we were now five days behind schedule, due to bad weather. We had come to our second major obstacle — the great ice falls. Randall left in a "white-out" with a party to establish a route through these ice falls. We had scarcely entered this mass of ice when a serac, estimated at ten tons, tore away and narrowly missed the party. The mountain was nipping at us. Shortly after this, a crevasse some fifteen feet wide opened just after the first rope team had passed.

Pierre had just taken the lead when a crevasse opened under him and he fell twenty feet with full pack plus snow shoes. It was a near disaster. We later appointed him "Chief Crevasse Explorer," but even this imposing title could not induce him to make a career of this.

The climbers developed an esprit de corps that would make a team of ants green with envy as they tirelessly hauled 60- to 70-pound loads through the dangerous ice fall and over the treacherous crevassed fields for four days.

Jim Prichard was gleeful as he operated the 16mm movie camera and anxiously waited for some loaded climber to take an embarrassing tumble.

Camp IV was established at the base of Karsten’s Ridge at 11,000 feet. That night we were "dog tired" and preparing to sack out on the glacier when we were jolted by a sharp earthquake. Helpless climbers, scrambling out of frail tents in scanty clothing, saw billows of snow above and felt the mist on their faces. It took some time to realize we had been spared. Few slept well that night.

Karsten’s is a knife-edged ridge which twists and turns up the mountain, ending at 14,600 feet (Brown's Tower): this was our route. The first attempt to find a route up the ridge was repulsed and the scouting party was forced to turn back when Sean Rice was almost swept away by an avalanche. At 7pm the same day, Randall and a party left for a second attempt at the ridge.

Disregarding this disaster, the party fought up the ridge foot by foot until they found a spot to establish Camp V.

The party moved up the upper part of Karsten’s Ridge with the precision of a fine watch. The first team shoveled cornices clearing the route, and the second team followed putting in ice screws, pickets, and fixed ropes.

We began in the fog, but as we reached Brown's Tower (14,600 feet), the mountain was in sunlight. From this spot we got our first look at our objective the South Peak. We were exuberant.

Camp VI was established at 15,500 feet and our high camp was made at I 7, 700 feet. The long hours, fatigue, lack of rest, and altitude were starting to show. Three climbers lay ill in their sleeping bags. The weather was beginning to turn sour. On July 9, Randall called the summit assault.

For hours on end we trudged upward, looking and feeling absolutely insignificant against the huge face of the South Peak. It was snowing when the first team hit the summit and continued even as the last rope came onto the summit. We congratulated each other, wiped away a few tears, and then went to work. Chuck De Hart, who had slept with the radio all the way up the mountain to keep the batteries from freezing, got it out and made contact with Anchorage. This was the first call in history from the summit of North America's tallest mountain.

Meanwhile, the snow stopped, the sun came out, and we were rewarded with a breathtaking view from the pinnacle of North America.

On the final day, we had only to ford the McKinley River before being back in civilization. This turned out to be no easy task. Seven of us were swept away by the strong torrents and one climber was almost drowned. In this melee we lost ice axes, cameras, climbing gear, and ropes, and received our only abrasions of the trip.

We had a farewell dinner in Fairbanks, Alaska, where the climbing party gave Al Randall a tearful standing ovation and thanked him for having led us up the Mountain. We heard Randall, in a choked voice, thank us for having come with him. The Mountaineers' McKinley Outing had been a complete success because of careful planning and attention given each minuscule detail, the close teamwork of the party, and the exceptional leadership qualities of Al Randall.

Charles “Charlie” Crenchaw

Charles “Charlie” Crenchaw

This article originally appeared in our Fall 2019 issue of Mountaineer Magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, click here.

Charles Crenshaw

Charles Crenshaw