Enjoy an excerpt below from Written in the Snows, written by renowned local skiing historian Lowell Skoog and published by Mountaineers Books. In it, we read the account of the first slalom ski race in the Pacific Northwest, an event characterized by equal parts thrill and chaos.

Chapter 6: A Winter Paradise

Chasing silver

By the winter of 1934, Mount Rainier had nearly everything a skier could ask for - open slopes, deep snow, comfortable lodging, and a lively social scene. But for Hans Otto Giese and a few friends, the mountain lacked one thing: a true skiing spectacle. Giese was a proponent of the alpine disciplines of slalom and downhill racing, having gained knowledge of and enthusiasm for them in Europe. He helped organize the first Pacific Northwest Ski Association slalom race at Snoqualmie Pass in February 1934, two weeks after Seattle Municipal Ski Park opened there. A couple days before the Snoqualmie Pass slalom was held, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer announced sponsorship of a “Thrilling Downhill Ski Race” to be staged on Mount Rainier later that spring. Giese was the race’s leading booster. The race would run from Camp Muir to Paradise, a distance of about three and a half miles with 4,600 feet of descent.

For two months leading up to the race, the P-I pumped up the event, soon dubbed the Silver Ski Championships by the paper. Royal Brougham, an old-school sports writer who didn’t worry much about the difference between reporting the news and making it, portrayed the race like a Kentucky Derby on snow…

At Muir the racers sported a motley assortment of gear. A few chose long, heavy jumping skis for the race. Others nailed lead strips atop their skis for added weight and stability. Some skis had metal edges, but many did not. Racer Emil Cahen wore a football helmet, the only participant with head protection. Friends recalled that he took a lot of kidding for it. As the starting time approached, Otto Sanford raised a red flag high above his head and eyed the official watch in his left hand. At precisely 1:30 p.m., Sanford dropped the flag and someone fired a pistol, sending the men on their way. Spectator Harry Webster, watching from far below, recalled, “It looked like someone had poured a bottle of ink on the snowfield below Camp Muir.”

Hans-Otto Giese, Fred Ball, and Andy Anderson. Photo courtesy of W.J. Maxwell Collection, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, neg. no. 18134.

Hans-Otto Giese, Fred Ball, and Andy Anderson. Photo courtesy of W.J. Maxwell Collection, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, neg. no. 18134.

Racer John Woodward remembered that a dry, cold wind had frozen the snow near the start. “It was like little ball bearings of ice,” he said. “It’s the fastest snow you could ever have. We all got in a crouch, and all of a sudden the wind was screaming and the fronts of the skis are vibrating and sort of flying in the air.” Racers faced daunting choices - whether continue in a deep crouch toward a likely crack-up, attempt to turn with racers hurtling on either side, or stand up to brake using wind resistance. Woodward chose the third option. “I’d never tried it at that speed, so I didn’t lean forward far enough, so when I stood up a little too quick, it was like fifteen pillows hit my chest and boom. When I stopped tumbling one of my ski tips was gone. Busted clear off.”

Other racers remembered similar spills. “I had gone into Spartan training doing deep knee bends during weeks of preparation in order to prevent the cramping effects of a deep crouch position against expected headwinds,” all-around mountaineer Wolf Bauer recalled. “The extra speed cost me both poles, goggles, and a broken ski still hanging precariously together with a steel-edge fastening - result of a somersault at near sixty miles per hour.” As he remembered, “Most of us had waited too long to check speed and change course because of the traffic on all sides. When checking became imperative, the smooth snow surface suddenly changed to shingled windrows and waves, bringing about a fearsome explosion of cartwheeling humanity. It was not until the race was over that I learned how others behind me had spilled at the same time and place. Somewhat dazed I picked myself up, deciding not to waste time looking for my poles and goggles, and immediately got under way again.”

Don Fraser avoided the worst. “Fortunately, I was soon out in front of the mob headed for Little Africa,” he said, “so I didn’t witness the terrible collisions that took place just behind me.” One of the most serious involved Ben Thompson, chief climbing guide on Mount Rainier, who collided with another skier who’d cut in front of him. Thompson woke up minutes later with a broken jaw and two teeth knocked out. He walked down from Anvil Rock to the foot of Panorama Point, where he was put on a toboggan and taken to Seattle to have his jaw set. The youngster that Thompson hit suffered torn shoulder ligaments. Another had a broken collarbone.

Fraser stayed near the front of the pack. Near McClure Rock and above Panorama, he recalled, “there were large mounds (like small jumping hills), and one was airborne 100 feet or more on each one. The speed, at this point, was far more than any of us had ever gone before - even on a jumping hill. Tired legs took their toll. Many skis and poles were broken and some god-awful falls took place.” Below McClure Rock, Fraser said, “the shellac was clear off my skis and they were sticking. You’d suddenly be thrown forward when you hit sticky spots. I didn’t fall, though.” At the Panorama Point control gate, Fraser led, followed closely by Carleton Wiegel, then Alf Moystad, Bauer, and Giese.

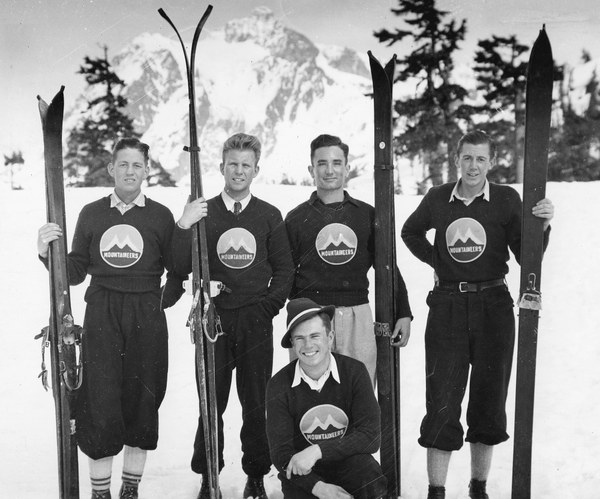

The Mountaineers Ski Team at Mt. Baker in the mid-1930s: Scott Osborn, Wolf Bauer, Bill Miller, Tim Hill, and Don Blair (in front). Photo by Robert H. Hayes, The Mountaineer annual, 1936.

The Mountaineers Ski Team at Mt. Baker in the mid-1930s: Scott Osborn, Wolf Bauer, Bill Miller, Tim Hill, and Don Blair (in front). Photo by Robert H. Hayes, The Mountaineer annual, 1936.

On the sticky snow below Alta Vista, Fraser and Wiegel were running over the snow, pumping with their ski poles and striding as much as their leather boots would allow. Loudspeakers were set up at Paradise, and sports editor Royal Brougham called the action. “My knees were shaking,” Fraser recounted. Wiegel poled frantically to catch up, but fell short at the finish line by about a ski length. Fraser crossed first to win in a time of 10 minutes, 49.6 seconds. Following Wiegel by a few minutes were Moystad, Tom Heard, Bauer, and Giese. Racers continued to arrive for another half hour.

Even the officials were not necessarily safe. Mel Borgersen, who was monitoring the race, somehow got hurt. “I’m sure it was Mel,” John Woodward recalled. “The ski patrol was bringing him down in a toboggan. They weren’t trained in those days, and they both fell down and the toboggan got away. He’s strapped in and it’s heading for the top of Edith Creek basin. Right below Panorama, those cliffs there. He was heading right for that and he knew it, so he rocked himself back and forth and finally rocked and turned himself upside down and skidded to a stop, with him underneath the toboggan.”…

Nearly three thousand spectators witnessed the 1934 race. The Seattle Times reported the next day: “On the steep ski course from high Camp Muir to warmer Paradise today were tracks - scores of tracks; a broken ski tip here and there; holes dug by spilling skiers; control flags still marking a stretch of ski terrain where yesterday was run as astounding a ski race as America ever saw.”

This article originally appeared in our winter 2023 issue of Mountaineer magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, visit our magazine archive.

Lowell Skoog

Lowell Skoog