It was 1963, and a group of 166 Mountaineers were embarking on a Summer Outing into what is known today as the North Cascades National Park. That day the park was still a dream; The Mountaineers and other partnering conservationists had been working for nearly 60 years to achieve a park designation. Mountaineers chairman Chet Powell chose “these wilderness alps” as the location for the year’s annual outing, believing that “as much of the area as possible should be seen by as many as possible” to advance efforts to protect the region.

The three-week trip consisted of various small-group climbs, casual hikes, campfire chats, and even butterfly-chasing. The trip report, included in the 1963 Mountaineers annual, celebrates the natural beauty of the Cascades while detailing the informative, awe-inspiring, and at times comical situations they encountered.

Getting there

The journey began, and nearly ended, with a roadblock. Far from any summit, the group arrived at a river with no means to cross. After a long period of lingering, one individual was brave enough to face the waters and abandon the other 165 members to eat wild huckleberries and contemplate defeat.

Horseshoe Basin. Photo by Ruth Ittner.

Horseshoe Basin. Photo by Ruth Ittner.

Although impromptu trail maintenance was not part of the plan or anticipated group skill set, Ray Courtney, a determined Mountaineer unwilling to let the tantalizing mountains remain in the distance any longer, “splashed across the stream and cut down the only cottonwood in the only strategic spot” to create a “deluxe bridge.” Needless to say, LNT ethics were slightly different in the 60s.

Marching onward, the group finally reached camp, where they were warmly greeted by an unrelenting mass of mosquitos. In an attempt to flee their welcoming party, many decided to escape to higher ground. As James Crooks recounts:

“Mid-morning of that day, swarms of unruly mosquitos put an abrupt halt to verbal activities. It was hurriedly decided to adjourn to a higher elevation and in due course a point at the base of the southwest face of Liberty Bell was reached.”

Sometimes you don’t make it to the top for the views, but for the respite from insects.

Awash in the beauty of nature

The climb to the base of Liberty Bell was short and not too technical, and set the mood for the rest of the trip. As the report notes: “While the ascent is stimulating, it is not so demanding as to preclude occasional contemplations of nature – a climb of saxifrage in a most inhospitable spot seemed infinitely delightful.”

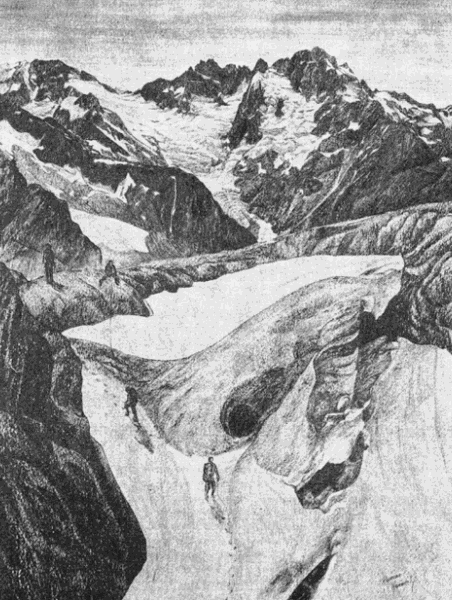

Cache Col - Spider and Formidable in background. Sketch by Ramona Hammerly.

Cache Col - Spider and Formidable in background. Sketch by Ramona Hammerly.

The party continued to be delighted throughout their journey by the many natural wonders the Cascades had to offer. While heavy with technical advice and route suggestions, the trip report is rich with reverence for all ecological findings. Members of the outing were continually awed by magnificent views and describe in detail the sensory joys of being in the outdoors. Soft needles blew through the breeze to provide “a memorable auditory experience.” The meadows were a “tapestry of beauty,” freckled with wild phlox, lupine, red-violet rockcress, and willow. Heather “easily won the prize as the most widespread flower,” accompanied by the paintbrushes, sandwort, and senecio that dotted the campsites.

Coyotes made an appearance, as did hummingbirds, ice worms, mice, and conies. Mountain goats could be seen traversing the rock faces, and climbers took note of their expert route-finding. The group was ecstatic to find arctic butterflies and a rare species of trailing azalea, suggesting that “the catalog of species found is incomplete,” and thus in dire need of preservation.

The climbs

Although eager to face the mountains, the group was quickly sobered by the rock faces in front of them. The first climb, a successful summit of Goode Peak, lasted 19 hours. Belaying and piton-placing took more time than expected, and the group didn’t return to camp until 1:30 am. After such an unexpectedly lengthy trip, the group realized what they were in for. “There was a tremendous elevation gain to be made from camp to the top of any of the nearby peaks,” the trip report describes. “Because of this, and the numerous route- finding problems involved, relatively few members of the outing succeeded in getting to the summits.”

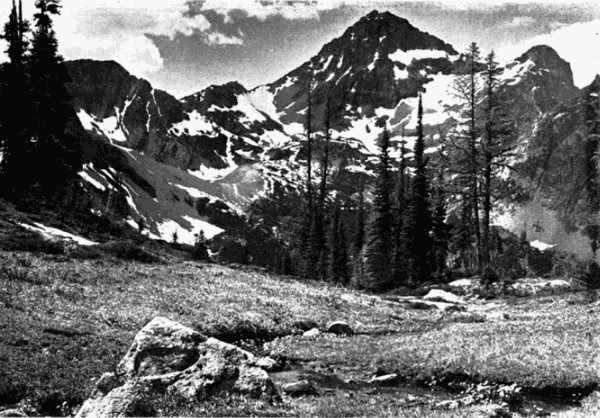

Mt. Buckner, Ripsaw Ridge, and Boston Glacier from Logan glacier. Photo by Gene Dodson.

Mt. Buckner, Ripsaw Ridge, and Boston Glacier from Logan glacier. Photo by Gene Dodson.

Next was an attempt on Mt. Logan. Encountering obstacles like thick brush, large gullies interrupting clear pathways, and view-obscuring clouds, the party struggled to find the proper route, or even the proper peak. While attempting to find their way, they stumbled across the summit cairn, and realized that their location “turned out to be the right peak, reached by the right route, although they had not known it until then.”

One party even encountered a frantic and enthusiastic yodeler who turned out to be a fellow Mountaineer working nearby at the U.S.G.S research station. According to the climbers camped on the glacier, a man 700 feet above them began to “ski-glissade down the snow, yodeling as he came.” His songs “echoed back and forth from Dome and Spire and repeated themselves again and again,” and his dancing descent downward “might well have been in a fantasy scene of a Walt Disney alpine movie.”

A group of three, one of whom had to be gently separated from her guitar, embarked on a courageous 19-hour traverse of Buckner. This climb was described by Hassler Whitney as “one of the most superb rock climbs” he had ever been on. A challenging endeavor, Hassler emphasized the importance of preparedness and skill when climbing. He shares:

“Earlier on the outing, a climber remarked to me that to cross some of these peaks one would probably have to take little risks because of the great lengths of the climbs. I would rather phrase this otherwise; to accomplish such a climb with safety, the party must consist of good climbers, with a really competent leader who can keep the party moving steadily and safely... one must use intelligence, observation, study, and experience.”

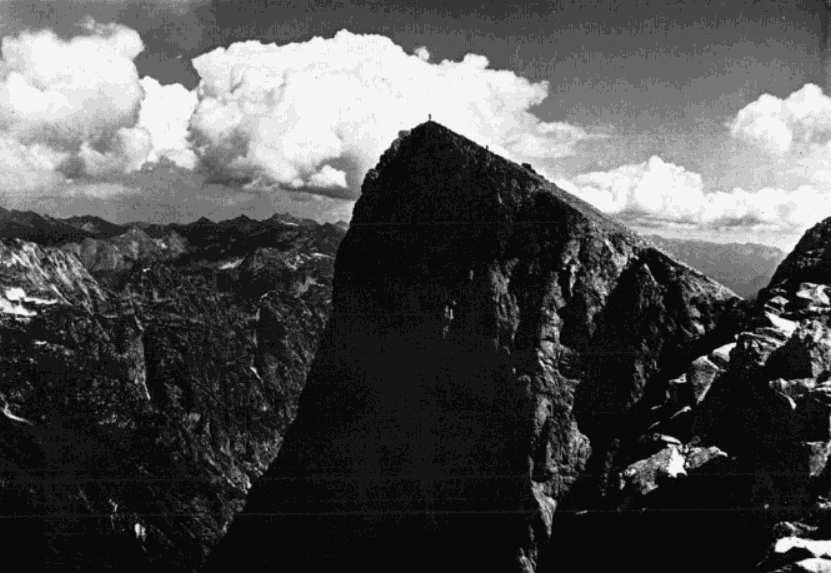

Black Peak. Photo by George Dragseth.

Black Peak. Photo by George Dragseth.

Throughout the trip more climbs were made of Mt. Logan and Booker, as well as Lizard, Le Conte Ridge, Dana Glacier, and Dome Glacier. The climbers marveled at their experience “camping at elevations slightly above 600 feet and traveling high, always with a view.” Everyone agreed it was a wilderness experience they’d never forget.

Paving the way for a national park

It would take only five more years for the North Cascades to become a national park, thanks in part to The Mountaineers and other recreationists and conservationists who advocated for its protection. After the summer outing, Mountaineers members were not only inspired by the thrill of recreation, but awed by the resplendence of the mountains and the species they had never before seen.

The trip report closes with deep reflection, sharing that “there were questions we could not answer. In the realm of ecology, there is still much room for exploration in the mountains of the North Cascades.” These questions may perhaps never be answered, but we can enjoy and reflect on the magic, mystery, and mosquitos found in the North Cascades all those years ago.

This article originally appeared in our fall 2022 issue of Mountaineer magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, visit our magazine archive.

Skye Michel

Skye Michel