We thought we were in a safe spot, but before we knew it, my Dad was falling into a crevasse. Moments earlier, we had arrived back at high camp and started to unclip from the rope – the tether that allows climbers to catch one another in the event of a fall. Then, in an instant, the snow collapsed under Dad. He pulled his leg out, but was unable to gain purchase and started sliding down the slope into the void. Only one of us, a new climber named Scott, was still attached to him.

For months, we’d done our best to prepare for the unexpected. The stakes are higher on winter ascents of Rainier. Cold, storms, avalanches – all these risks are heightened. To put things in perspective, out of the 5,000 people who summit Rainier each year, only about 50-100 do so in winter. The difficulty of a winter ascent didn’t deter our group of hopeful teenagers. In fact, it’s why we chose it.

The year was 1977 and we were a couple of years out of high school; young cadets enrolled in the U.S. Air Force Academy. Although only half of us had glacier experience, we set our sights on this objective because we wanted an adventure that would push us, that would force us to train hard and work together.

We wanted a challenge. But now Dad was over the edge, and the fate of our expedition was hanging on a line.

Groomed in the Olympia Mountaineers

My love and knowledge of the outdoors was born in the Olympia Mountaineers. Both my parents were members, and the club’s backpacking course led to many family trips with my sister, our dog Blitzen, and me.

The Olympia Mountaineers also taught my Dad and me how to climb. He enrolled in the basic climbing course, and a few years later, after I turned 16 (the minimum age requirement) I followed in his footsteps. Together we became versed in navigation, glacier travel, crevasse rescue, and more. One highlight of the course was heading to Mount St. Helens to practice digging snow caves and surviving the night – a skill that proved essential when our tents were wiped out by a storm on the Rainier trip years later.

After completing the climbing course, Dad and I enjoyed many adventures in the backcountry, including a near-summit of Rainier and a successful summit of Mount Hood. My climbing resume was growing, and Dad was becoming quite the mountaineer, completing all of Washington’s six major peaks.

The team prepares

A month after Dad and I climbed Hood in June 1975, I was flying upside down in a two-seat fighter jet above Pikes Peak, one of the highest points in the Rocky Mountains. I was enrolled in the Air Force Academy and living on campus, just north of Colorado Springs. Pikes was an hour and a half away – the new mountain in my backyard. I didn’t know it then, but in 1977 Pikes would serve as our training ground for Rainier.

Pikes stands at 14,110 feet (just 300 feet short of Rainier). To test our mettle, our cohort of aspiring mountaineers decided to make an attempt in February. Our group consisted of six cadets: Steve Coucoules, Steve Hocking, Carl Mallery, Randy Nelson, Scott Smetana, and myself. Another cadet, Paul Avery, also joined us, but he couldn’t make the Rainier trip.

Moving in snowshoes and hauling our tents, ropes, and glacier gear, we trudged up the mountain. It was cold. Our packs were heavy. The air was thin. We developed symptoms of high altitude sickness: headaches, nausea, light-headedness, muscle aches, general weakness. We were alone, isolated. Nonetheless, we did it. Twenty-five hours later, we were back, in one piece, with our first winter summit under our belts.

CROSSING THE COWLITZ GLACIER. PHOTO COURTESY OF CARL MALLERY.

CROSSING THE COWLITZ GLACIER. PHOTO COURTESY OF CARL MALLERY.

This experience taught us a lot about each other. We developed a level of trust. We saw and understood our capabilities. We came together as a team. Sure, it was hard. But we learned we were capable of embracing adversity.

We continued to train together, turning our attention to Rainier. In addition to climbing Pikes, we spent many days honing our glacier climbing skills at Stanley Canyon. For an expedition of this magnitude, we wanted an experienced leader to help us. We aimed high and asked acclaimed mountaineer Willi Unsoeld. Willi had famously pioneered a new route up Mount Everest in 1963 with Tom Hornbein. Willi, was now serving on the faculty at Evergreen State College, respectfully declined, but asked if one of his students to join us. We were delighted and welcomed student deGay Ernst to the team.

The final addition to our team was my Dad, Gene Barnard. In lieu of Willi, Dad agreed to serve as our climb leader and guide.

In March of 1977, we set off for the Pacific Northwest. Before heading for the summit, we took a final training day in the Paradise area of Mount Rainier. We used the area’s steep slopes to practice ice ax arrest, crevasse rescue, team arrest, and belay techniques.

After our training session in Paradise, we returned to town, where Willi Unsoeld and his wife dropped by to give us a sendoff for the Rainier trip. Willi regaled us with stories of his crazy climbing escapades in the Tetons.

“For me, Willi’s talk is one of the most memorable aspects of the whole adventure,” said Steve when I asked him about our trip years later. “Remember how he poked the tops of his tennis shoes to show how many toes he lost due to frostbite after his Everest trip?”

Up the mountain

No one was in line for climbing permits when we arrived at the Paradise Ranger Station. Something about the high winds and blowing snow meant we had the mountain all to ourselves. We were given climbing permits on the spot.

We trekked up to the “first come, first serve” shelter at Camp Muir. Once again, no one was waiting in line! In fact, the stone huts were buried in snow and it was clear no one had been up there in some time. We dug our way in as the wind howled. That night the thick stone walls vibrated around us under the force of the gusts.

The following day we stayed rooted at Camp Muir, telling ourselves the weather was too poor for routefinding. In reality, none of us wanted to step outside.

Eventually, we summoned the gumption to leave our shelter. The park ranger had told us that the “normal routes” were unclimbable. There hadn’t yet been enough snow to fill in the huge, extensive crevasses on Ingraham Glacier. Since we couldn’t use the popular Disappointment Cleaver-Ingraham Glacier Route, we’d have to assess the terrain and find our own way up.

With Dad leading the first rope team, we traversed steep slopes in high wind, our heavy gear trying to catch the gusts and sail us away. At last, we established our high camp on top of an ice cliff at 12,300 feet on the upper Ingraham Glacier. A harrowing night in high winds and heavy snow followed, with one tent nearly collapsing under the weight.

The next morning, our fourth day on the mountain, was a delightful improvement. We could see the top of the peak; it was so close. We reached the summit crater in clear, 4 degree weather and high winds: 14,410 feet… we did it!

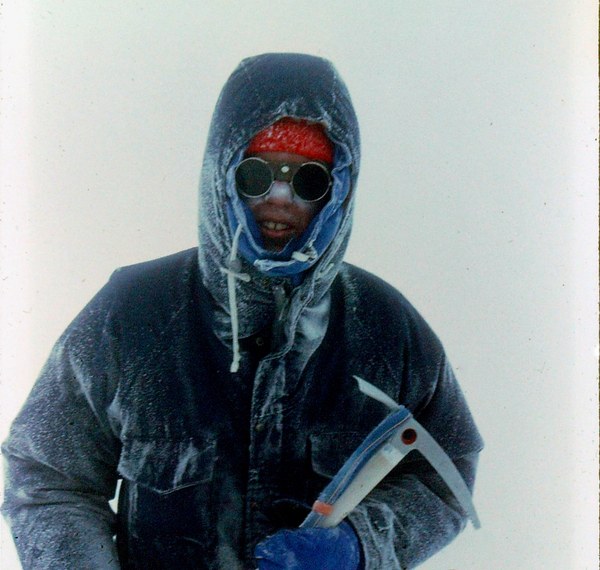

SCOTT SMETANA COATED IN RIME ON THE SUMMIT. PHOTO COURTESY OF SCOTT SMETANA.

SCOTT SMETANA COATED IN RIME ON THE SUMMIT. PHOTO COURTESY OF SCOTT SMETANA.

Steve Coulcoules celebrated by banging out 30 pushups and Scott joined with 40 jumping jacks. Our unorthodox summit party was in reference to a bet. Prior to the expedition, Steve bet Scott he could get us special dining rights at the Air Force Academy – a privilege typically reserved for our school’s collegiate athletes. Scott pulled it off, and leading up to the trip we enjoyed meals that were a huge improvement over our usual, strict Academy diet. As a fun homage to our status as “college athletes,” Steve and Scott enjoyed a workout session on the summit.

“It was a little harder than I thought it would be,” Scott remembers. “I had to jump straight up to get the crampons disengaged before spreading my legs.”

What goes up must come down

Descending to high camp, we walked through a brutal lenticular cloud. None of us could see the next person on the rope, let alone whoever was in the lead. To guide the way, we relied on the wands we placed on the way up.

Then, just when we thought we were safe, Dad took his fall into the crevasse. Throughout our trip, we’d engaged in a number of crevasse rescues hardly worth mentioning. Our large, external-frame backpacks acted like a cork in a bottle, catching us at our hips or waist before we plunged any deeper.

But this fall was different. Dad’s pack wasn’t catching him and he was sliding into the crevasse. Scott, realizing he was the only one still roped into him, hit the ground, hammering his ice ax deep into the snow. He dug into the snow with his crampons and held on with all his might.

Scott was one of the team members who’d never been on a glacier before this week. We looked on with baited breath as the rope stretching from Scott’s harness grew taut under Dad’s weight. All those training sessions working on ice axe arrest, it was all coming down to this. Dad used his rescue slings to start inching back up the rope. Just like we’d practiced, Scott held his position. He saved Dad and the expedition.

With the danger behind us, we turned our attention back to high camp. A storm was coming in and we feared how our tents would fare against the high winds and fresh snow. We decided to dig a snow cave.

Four of us slept in the cave while the other four slept in tents. Shortly after we laid down our heads, one of the tents collapsed in the storm and its occupants were forced to join the cave crew.

Throughout the night, we re-dug the door and vent holes to avoid sufficating in the cave. The first-timers found things surprisingly warm and quiet. Once again, our team’s practiced skills proved indispensable.

The next morning it took us two hours to dig out our equipment. Needless to say, it was quite the storm. Once again, we were faced with zero-visibility conditions, but our previously placed wands, coupled with a bit of routefinding, allowed us to navigate our way down. At long last, we were at the parking lot.

40 years… and back

As I wrote this story, I realized I only had one surviving photo of our trip. For the first time in 35 years, I reached out to the former cadets on our Rainier team. Within hours of contact, they were looking through their old photos, reconnecting me with the beautiful shots in this magazine and many more. Decades later, our team was still up to the task.

I'm grateful, but not the least bit surprised. That's a natural outcome of working so closely with each other, of leaning on one another in trying times.

The real story of our team isn’t Rainier, it’s those many months of preparation – climbing Pikes Peak, training at Stanley Canyon, taking a final practice day at Paradise. This is how we became good teammates. It’s what allowed Scott to catch my Dad’s fall, and it’s what allowed us to make it through the wind, snow, and white-outs.

I’m reminded that the best adventures don't happen alone. Build trust, earn trust. That's why I share this story from all those years ago. The trust we built, the summits we reached together, have sustained me ever since.

Scott Smetana ascending Ingraham Glacier to high camp with Little Tahoma in background. Photo by Gene Barnard.

Scott Smetana ascending Ingraham Glacier to high camp with Little Tahoma in background. Photo by Gene Barnard.

This article originally appeared in our Winter 2019 issue of Mountaineer Magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, click here.

Edward Barnard

Edward Barnard