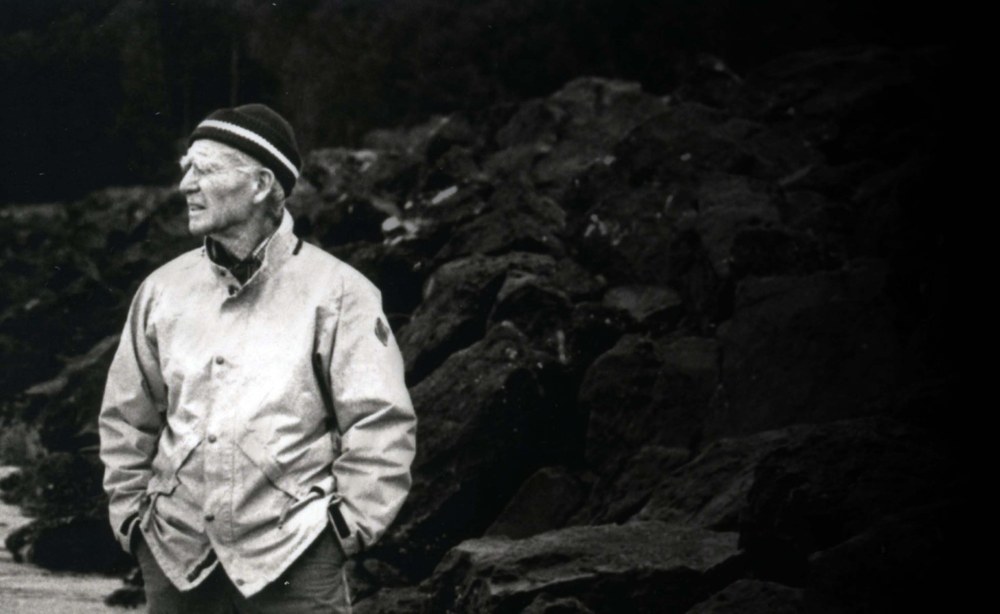

Wolf Bauer, one of The Mountaineers’ oldest and most distinguished members, passed away on January 23, 2016, a month shy of his 104th birthday. He was born on February 24, 1912.

Over the course of his long life, Wolf was honored by his community many times. He was named an Honorary Member of The Mountaineers in 1966, First Citizen of Seattle in 1979, recipient of the national Thomas Jefferson Award for volunteer service in 1985, and member the Northwest Ski Hall of Fame in 1994. He was profiled in the 1980 Mountaineer Annual and the Spring 2000 Mountaineer Bulletin. I wrote my own profile of Wolf for the 2005 Northwest Mountaineering Journal. In 2010, Wolf published his autobiography, together with Lynn Hyde, entitled Crags, Eddies & Riprap: The Sound Country Memoir of Wolf Bauer.

To understand the true impact of Wolf’s life, it helps to carry out a little thought experiment. In the spirit of the classic film, It’s a Wonderful Life, I’d like to imagine what the Northwest might be like today if Wolf had not come from Bavaria to the United States with his family in 1925.

Wolf’s association with The Mountaineers began in 1929, when, as a 17-year-old Boy Scout, he was awarded a free membership in the club. Wolf suspected at the time that his appointment was in recognition of his skiing ability rather than his character. He soon proved himself a formidable skiing competitor, with victories in many club races. In 1936, his three-man team, including Chet Higman and Bill Miller, won The Mountaineers Patrol Race, from the old Snoqualmie Lodge to Meany Ski Hut with a record time of 4 hours, 37 minutes, 23 seconds. Wolf’s stories of the race were a significant factor in its modern revival in 2014. His record stood for 80 years, beyond his lifetime, until it was finally eclipsed by my own team earlier this year, in 2016.

In the mid-1930s, Wolf organized and taught The Mountaineers first climbing course. In the midst of the course, he teamed with some of his students to complete the first ascents of Ptarmigan Ridge on Mt Rainier (1935) and Mt Goode in the North Cascades (1936). Ptarmigan Ridge wasn’t climbed again for 24 years, an indication of how far ahead of the times it was. On the other hand, Goode was climbed in 1937 and 1940 by different routes, suggesting that had Wolf’s party not succeeded, others would have done so soon.

LIKE A PIED PIPER, WOLF BAUER LEADS HIS STUDENTS ON A SNOW CLIMBING PRACTICE NEAR LUNDIN PEAK IN 1935-36. PHOTO BY OTHELLO PHIL DICKERT.

LIKE A PIED PIPER, WOLF BAUER LEADS HIS STUDENTS ON A SNOW CLIMBING PRACTICE NEAR LUNDIN PEAK IN 1935-36. PHOTO BY OTHELLO PHIL DICKERT.

More important than Wolf’s first ascents was the climbing course that helped make them possible. Although Wolf led the program for only two years, he laid the foundation for both the basic and intermediate courses and trained a cadre of instructors who carried on after his engineering career pulled him away. Lloyd Anderson, one of Wolf’s students, founded Recreational Equipment Co-op in 1938 to provide gear for the growing ranks of course graduates. Anderson, in turn, was a mentor to young Fred Beckey, who graduated from the intermediate course in 1940 and was soon making history on unclimbed peaks and routes throughout the Northwest.

Students in Wolf’s climbing course had to pass a written test that was similar to a college exam. In addition, they were asked to provide written descriptions of the climbing routes they had used. Soon these “Climbers’ Guides” were copied and made available to other climbers, the predecessor of today’s guidebooks. As Wolf’s students took over course instruction it was agreed that each lecturer would prepare his topic in outline form and submit it to the climbing committee for approval. By 1940, these mimeographed pages were published as The Climber’s Notebook, the first text in the nation devoted exclusively to teaching climbing. The Climber’s Notebook grew and was refined in the 1940s and 1950s to be published in 1960 as Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills.

Thus was launched The Mountaineers book publishing program. If there had been no climbing course, would The Mountaineers Books have ever been established? If Wolf Bauer had not launched the course, would others have eventually done it? These questions are impossible to answer, but it seems likely that the future would have been very different without Wolf’s early contributions.

In the 1930s and 1940s, The Mountaineers maintained a list of experienced climbers, graduates of the climbing course, who were willing to be called for search and rescue operations. A central committee made up of the climbers’ wives managed the phone list. While traveling in Europe in 1948, Wolf learned about the Bergwacht (“mountain watch”), a volunteer rescue group in Germany that was much like the National Ski Patrol in the United States. Wolf concluded that a similar organization was needed in the Northwest. His efforts led to the formation of the Mountain Rescue Council, which coordinated the efforts of The Mountaineers and other volunteer organizations with the State Patrol, Forest Service, and other government agencies. Wolf served as chairman of the Mountain Rescue Council for its first six years. After similar organizations sprang up around the country, the national Mountain Rescue Association was formed in 1959. Again, Wolf had been an essential catalyst for a new outdoor movement.

During a Mountain Rescue Council training session, Wolf Bauer (right) plans the approach to an accident site, circa 1953. Photo courtesy of Bob and Ira Spring.

During a Mountain Rescue Council training session, Wolf Bauer (right) plans the approach to an accident site, circa 1953. Photo courtesy of Bob and Ira Spring.

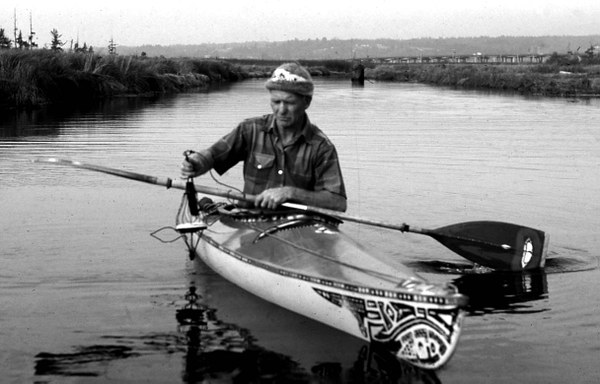

Wolf was introduced to foldboating in the late 1940s by his old scoutmaster, Harry Higman. Wolf took to the sport in a big way, founding the Washington Foldboat Club (later the Washington Kayak Club) in 1948. As he had with climbing in the 1930s, Wolf felt the sport needed an educational program so he designed a seven-week course and offered it through the YMCA. During the 1950s and 1960s, Wolf introduced hundreds of people to kayaking. He explored and mapped dozens of rivers throughout the Northwest, applying the now-standard kayak rating system (Class I through V) to each section that he and his friends had run. In so doing, he literally put the sport of kayaking on the map of the Northwest. He designed some of the earliest fiberglass kayaks in the U.S. and helped open sea kayaking in the San Juan and Gulf Islands, Barkley Sound and along the east and west coasts of Vancouver Island.

Wolf’s involvement in kayaking led to an interest in the conservation of shorelines and free-flowing rivers. Having kayaked the Mayfield and Dunn canyons of the Cowlitz River in the 1950s, he was saddened by the construction of dams that flooded these unique canyons in the 1960s. This led him to an effort to protect the Green River Gorge from development. Creation of the Green River Gorge Conservation Area in 1969 would likely not have occurred without Wolf’s efforts.

Wolf’s growing interest in conservation led him to launch a new career as a shore resource consultant in the 1970s. His observations on the interaction of water and land were incorporated into Washington’s landmark Shoreline Management Act of 1971. As a consultant, Wolf guided the restoration of dozens of beaches around Puget Sound (called “Bauer Beaches” by the Department of Ecology). They include Tolmie State Park, West Point beach at Discovery Park, and Golden Gardens Park in north Seattle. Before Wolf’s influence, beach erosion was typically addressed by dropping in huge boulders to create bulkheads. Wolf learned how to use gravel, contouring, and the removal of bulkheads to stabilize erosion and produce a beach that was both consistent with shoreline ecology and welcoming to the public.

Without the influence of Wolf Bauer, the conservation and outdoor recreational world, and indeed, the beaches of Puget Sound, would have been vastly deprived in so many ways.

Wolf Bauer guides the fiberglass Tyee I kayak that he designed along the Snohomish River in the 1960s. Photo courtesy of the Wolf Bauer collection.

Wolf Bauer guides the fiberglass Tyee I kayak that he designed along the Snohomish River in the 1960s. Photo courtesy of the Wolf Bauer collection.

This article originally appeared in our Spring 2016 issue of Mountaineer magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, click here.

Lowell Skoog

Lowell Skoog