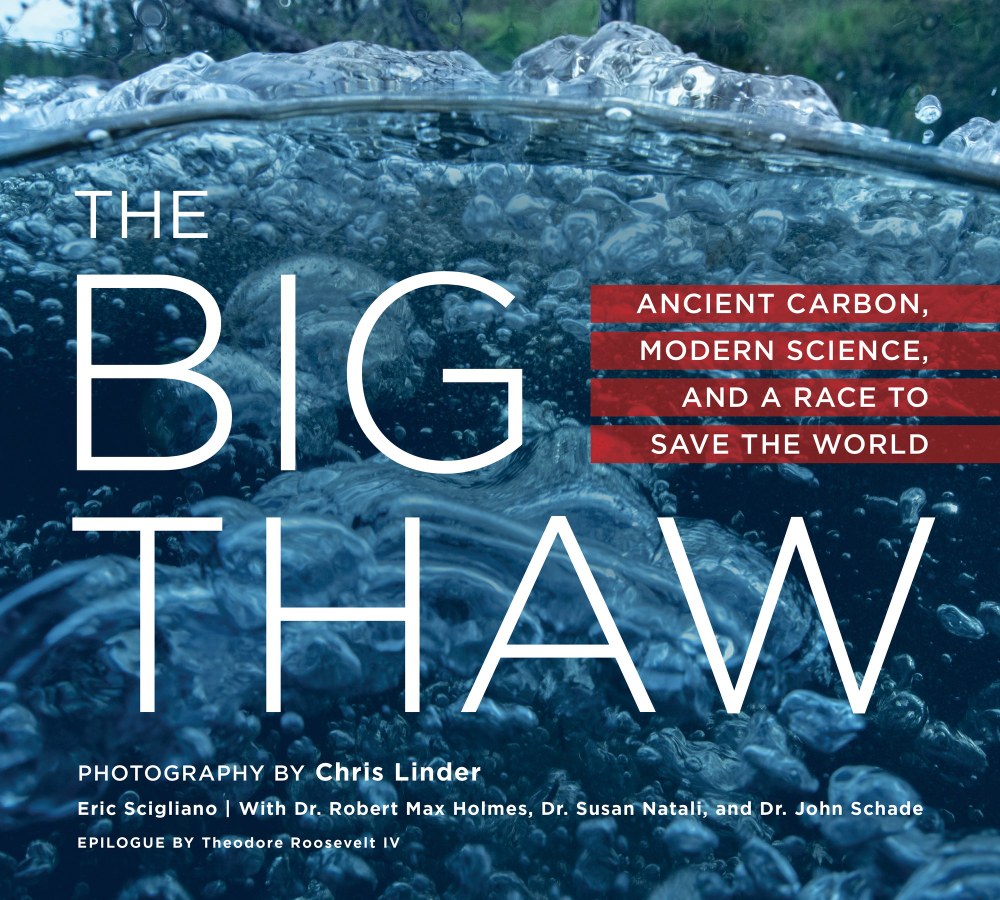

Here is an excerpt from Dr. Robert Max Holmes' essay in The Big Thaw: Ancient Carbon, Modern Science and a Race to Save the World, an October 2019 release from our conservation imprint Braided River. (And save the date: Max Holmes and photographer Chris Linder will present at our Seattle Program Center in November.)

The Big Thaw

It's not hard to separate the optimists from the pessimists when standing on the tarmac in Yakutsk, Siberia. The optimist looks at the aging twin-engine plane our group of twenty-five undergraduate students and scientists is about to board for a four hour flight to Cherskiy, deep in the Siberian Arctic, and is comforted by its many decades of success at traversing one of Earth’s Polaris most remote and inhospitable environments.

Max Holmes, lead scientist at Woods Hole Research Center, returns to camp after a long day in the field. Yukon-Kuskokwim (Y-K) Delta, Alaska.

Max Holmes, lead scientist at Woods Hole Research Center, returns to camp after a long day in the field. Yukon-Kuskokwim (Y-K) Delta, Alaska.

The pessimist looks more closely at the battle-scarred plane and shudders at the countless horrific ways that its good luck streak could end. I fall somewhere in between and I suspect my friend and colleague Chris Linder does as well. For the past decade we’ve traveled together over much of the world—from the Amazon and the Congo in the tropics to the Siberian, Canadian, and Alaskan Arctic—all the while doing our best to balance risk and reward as we strive to understand how Earth works and how it is changing.

Polaris students collect water samples from the clear waters of the Sukharnaya River.

Polaris students collect water samples from the clear waters of the Sukharnaya River.

My tools are those of an environmental scientist—sampling equipment, water quality sensors, permafrost drills, and the like—while Chris’s are those of a professional photographer. Chris’s photos also illustrate the human story that is always part of the scientific process, but that is seldom evident in the sterile pages of a journal article or a textbook. And arguably there is no other place on Earth where the scientific story and the human story intersect as powerfully as they do in the Arctic.

As temperatures in the Arctic rapidly rise at twice the global rate, permafrost—carbon-rich frozen soil—is thawing. This is cause for alarm beyond the Arctic, as permafrost contains much more carbon than has ever been released by burning fossil fuels. Thawing releases greenhouse gases into the atmosphere and contributes to rising temperatures worldwide but also causes more localized calamities within the Arctic.

The roots of ancient plants, possibly dating back to the Pleistocene, are exposed as permafrost thaws along the Kolyma River.

The roots of ancient plants, possibly dating back to the Pleistocene, are exposed as permafrost thaws along the Kolyma River.

As the Arctic ground—frozen for thousands, even tens of thousands of years—thaws and resettles, human infrastructure, including houses and roads, crumbles, along with the ecosystems that are so central to the lives of most Arctic residents. In addition, people living in coastal communities face increased coastal erosion and sea level rise as they watch the ocean encroach on their land, homes, and villages.

A massive slab of thawing permafrost leans over the banks of the Kolyma River in the Siberian Arctic, dwarfing Sergey Zimov in his boat.

A massive slab of thawing permafrost leans over the banks of the Kolyma River in the Siberian Arctic, dwarfing Sergey Zimov in his boat.

Yes, there is cause for alarm. There is more carbon in the permafrost than currently exists in the atmosphere today, and it threatens to be released on an epic scale. However, our hope is that the story from the Arctic, along with the stories of these young scientists who are not afraid to ask questions and who approach research with creativity and resolve, acts as a catalyst for change.

We believe the first step is to truly understand the scale and urgency of the problem and then to communicate what we have learned beyond the science community to our neighbors and local communities, to the media and our elected officials. This is core to our work at Woods Hole Research Center and our reason for this book with our publishing partner, Braided River. As my colleague Sue Natali says, there is a lot of bad news.

The good news? Now we know.

A glowing green band of the aurora borealis arches over the taiga, Siberia.

A glowing green band of the aurora borealis arches over the taiga, Siberia.

Dr. Robert Max Holmes is deputy director and senior scientist at the Woods Hole Research Center. He is an earth system scientist who studies rivers and their watersheds, and how climate change and other disturbances are impacting the cycles of water and chemicals in the environment. Dr. Holmes is also interested in the fate of the vast quantities of ancient carbon locked in permafrost in the Arctic, which may be released as permafrost thaws, exacerbating global climate change. He previously served as director of the National Science Foundation’s Arctic System Science Program and in 2015 was elected National Fellow of the Explorers Club.

All photos by Chris Linder, Courtesy of Braided River.

Mountaineers Books

Mountaineers Books