I’ve heard from a lot of forest-loving hikers over the past few years that they feel devastated and sad about the fires that have burned through vast swaths of Oregon’s forests, “destroying” some of their favorite places.

I get it. A story I tell in the introduction of Oregon’s Ancient Forests: A hiking guide hinges upon bushwhacking deep into the Opal Creek Wilderness to a grove of giant trees set in a lush magical fairy-land forest and then celebrating the importance of the activists who worked so hard to protect that special place from logging a decade earlier. That place is now covered in charred piles of the fallen trunks of those giants, the soil blackened, the dense green canopy reduced to blackened spears - an impact of the Beachie Creek fire of 2020 that had been nearly unfathomable.

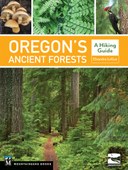

View from the north side of Waldo Lake, 22 years after the Charlton Butte fire, Chandra LeGue

View from the north side of Waldo Lake, 22 years after the Charlton Butte fire, Chandra LeGue

Yet I try to give my fellow mourners a message of hope, of certain renewal, and the exuberance of life. I tell them that “one day” it’ll come back, and that once long ago, the forest they hold in their memory was also born from fire. It can be a hard message to hear, and harder to believe given the brief moment in time we occupy.

If you’re new to Oregon’s Ancient Forests, the book dives into the natural role of fire in a variety of ancient forest types and goes into how human management has altered this role and impacts in forests. Two excerpts defines and summarize things:

“An ancient forest in western Oregon might be one that is recovering from a major fire that burned a century ago, and, while on the young side, has developed naturally with large snags, down wood, a variety of tree species, dense patches, and some five-hundred-year-old trees that survived the fire. In eastern Oregon, an ancient forest might have a few large old trees that survived dozens of fires, and the understory might have reestablished many times, leading to a mixture of ages and sizes scattered widely in the forest.” (page 39)

“Fire truly is an agent of change in Oregon’s forests. It is by far the most significant disturbance in terms of scale and effects, and it is a key process that represents a way that nature renews itself and shapes our living landscapes. For as long as there have been trees in Oregon, fire has been part of our forests. Historically, different forest types and climates in Oregon have experienced different fire regimes. In some forests, fire tends to burn infrequently and more severely, while other forests tend to burn more frequently and less severely—and everything in between. The fire regime in a moister forest type and climate like the Coast Range, for example, would likely recur at a long interval of a few hundred years but at a high severity where many of the trees would die. In a dry ponderosa pine forest, we would expect fire frequency to be much higher—every five to fifteen years—but fires would be less severe, mostly killing small trees along the ground.

While different regions and forest types evolved with different fire regimes, individual tree species are also adapted to fire in different ways. Some species, such as ponderosa pine, evolved to be tolerant of fire. These trees have thick bark to protect their cambium (the living layer of a tree just under the bark) from the frequent, generally low-intensity fires that tend to burn in the dry ponderosa pine forest type. Other species like lodgepole pine have adapted to unlock their cones to release seeds after a fire to quickly begin the process of regrowth. With thick bark and a love of growing in sunny, open areas, Douglas-fir trees, though often found in moister forest types that don’t experience fire often, are also well-adapted to fire. In an ancient Douglas-fir forest, the biggest, oldest trees often have blackened bark near their base, showing that they lived through a fire, while tree species typically found in moister environments or at higher elevations might not have such adaptations and tend to perish in a high-severity fire.

While fire does kill trees—sometimes just a few and sometimes vast landscapes depending on the severity and intensity of the fire—it also has a rejuvenating effect on forests. The trees that die in a fire are recycled naturally as snags and down logs, stabilizing and enriching the soil and providing much-needed habitat for species like woodpeckers, bluebirds, and bats that depend on abundant dead trees. Fires reset the understory where it may have grown very dense, allowing different species to thrive in burned patches.

Unfortunately, the natural cycles of fire have been disrupted—significantly in some areas—since Oregon’s settlement by Euro-Americans. Over the past century, logging has removed the largest and most fire-resistant trees in many areas, making forests less resilient to fire. Even more damaging are fire management policies that sought to prevent and put out fires whenever and wherever they started. This approach has led to an unnatural buildup of fuels and dense undergrowth in areas where frequent fire was the norm. While these changes in fuels and forest structure can affect fire severity, weather conditions determined by climate are more of a deciding factor than fuels in how fires burn. Over the long term, we still need to work to reduce the impacts of climate change, as well as prepare for them.” (Page 52-53)

Having this context and basis of understanding for both the natural and changed role of fire in forests can help us realize that every forest you or I have ever hiked through has been impacted by fire. And, in my humble opinion, the impacts of fire make burned forests some of the most interesting and beautiful to hike in. Here’s one example:

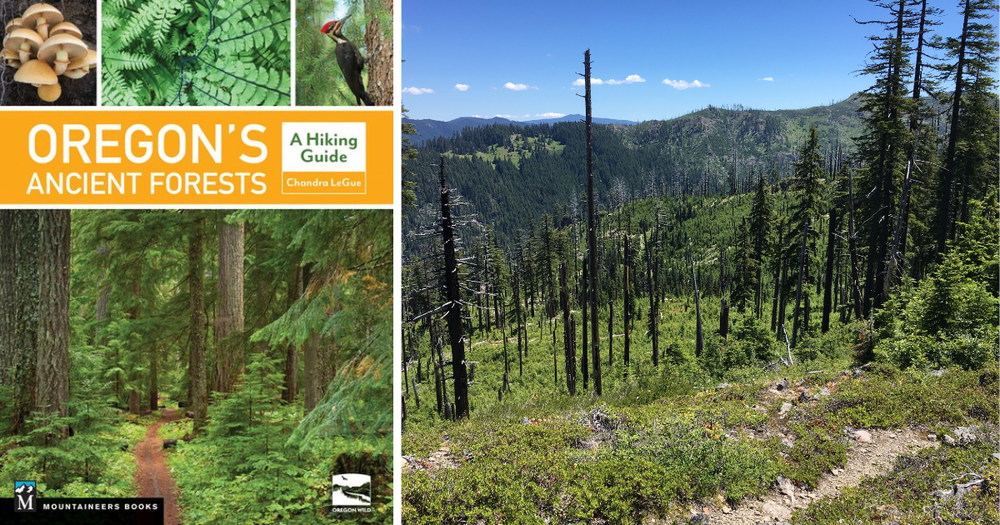

Warner Creek fire 25 years later, Chandra LeGue

Warner Creek fire 25 years later, Chandra LeGue

Not long after moving to Eugene, Oregon for graduate school, I took a field trip to the Warner Creek fire area outside of Oakridge. At that time it was 10 years since the 1991 fire. I remember the tall black snags rising tall above, and sapling trees crowded all around me -- head high and coated in dew that soaked through my sub-par rain gear. I’ve revisited the area a few times in recent years (now nearly 30 years post-fire!) and the hike along Bunchgrass Ridge through the burned area is one of the most exciting I know: Beargrass flowers thrive in the openings, butterflies and native bees enjoy the diversity of wildflowers, young trees are growing tall, and snags and down logs from the fire are still intact - storing water and carbon and providing a source of nutrients to the forest floor. (As I write this, the Cedar Creek Fire is still active and burned through much of the 1991 Warner Creek burn area. It is too soon to know how this fire impacted the area.)

If you look carefully on any forest hike, you can see the signs of fire everywhere.

Burned base of an old Douglas-fir tree, Chandra LeGue

Burned base of an old Douglas-fir tree, Chandra LeGue

In wandering many trails across Oregon while researching Oregon’s Ancient Forests, I relished finding these signs, both overt and subtle. On the Upper Middle Fork Willamette River trail I took joy in the blooming fireweed in openings ringed by tall blackened snags and mixed with regrowing trees seeded by living mother trees. On Grizzly Peak outside of Ashland, tall shrubs offered berries to birds while snags framed the view over the Bear Creek valley. And on the Imnaha River Trail on the edge of the Eagle Cap Wilderness, snags and 10 year old seedlings offered shade from the hot sun.

Subtle signs can take more sleuthing or a more trained eye. Large-diameter Douglas-fir trees in a moist, western Oregon forest might not seem like they’ve known fire, but on trails like Brice and Goodman Creek you can spot these giants with fire-blackened bark on the downhill side - remnants from a past fire they survived due to thick bark and high limbs.

But things are always changing. Since writing the book 4 years ago, roughly a dozen of the included hikes in my book have been dramatically changed by fire in that time. Some may not be reopened for years: Opal Creek, South Fork Breitenbush, Clackamas Riverside Trail, and Augur Creek. One, the Delta Old Growth Grove on the McKenzie River, will likely not be restored as a trail. One hike, Black Canyon on the west side of Waldo Lake, burned just this year but it will take time to know what condition the area is in and when it might reopen. (Find trail closure and condition updates for Oregon’s Ancient Forests: A hiking guide at this link.)

As wildfire crept (or sped) closer to communities and favorite scenic corridors all over Oregon in recent years - from the Columbia Gorge and the Clackamas, to the McKenzie and the Rogue Rivers, to the John Day and the Imnaha - we’ve had a chance to see up close and personally the effects this force of nature has on everything from our homes and infrastructure to recreation and water. These recent fires have brought fire more into focus for many of us, and too close for comfort. But the evidence all around us is that our forests and rivers were born in and shaped by fire. It can be hard to visualize that some of our most iconic ancient forests and favorite places to hike - like Opal Creek - will ever be the same. But, like countless burned forests we know and love today as lush, mossy sanctuaries, these forests will recover. In the meantime, we can learn to look for the evidence of past fires and imagine the forests that will grow from the ashes as they have many times before - different, but just as vibrant and interesting to explore.

Chandra LeGue

Chandra LeGue