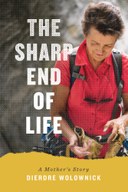

Dierdre Wolownick has lived an interesting life - mother, wife, teacher, musician, linguist, writer, runner and climber. Her son Alex Honnold is one of the two or three most famous rock climbers in the world. Dierdre herself started climbing late in life and at age 66 she climbed El Cap, making her the oldest woman to accomplish the feat. Find out how the author of The Sharp End of Life: A Mother's Story keeps life exciting.

A Q&A with Dierdre Wolownick-Honnold

You’ve summited Yosemite’s iconic, 3000-ft El Capitan with your son, famed free-soloist Alex Honnold — in fact you’re the oldest women to do so. How did you prepare for that incredible undertaking?

By baby steps. I had to ‘backwards engineer’ the task ahead of me: to break it down into smaller tasks that I could work on each week. I had to find out what ‘jugging’ was (Alex told me that I needed to know how to jug—use jumars—in order to climb it.) But I didn’t know what that entailed. So I went online, found out what that meant, then asked all my climbing friends if they could lend me some and show me how to use it. Then I had to find out where I could set up a rope to practice on a regular basis. Lots of research!

Once that was done, I had to find friends willing to help me practice indoors (the gym where I set up insisted I have a back-up belay). Once I started taking my practice outdoors, I needed to find a place to stay in Yosemite so I could train on real walls. I trained mostly on El Cap, so I could ‘make friends’ with it and mitigate what Tommy Caldwell calls “the intimidation factor” of such an incredible wall. I drove to Yosemite every week for 17 weeks to train, sometimes with friends, sometimes alone. Since I usually went on weekdays, I was alone for most of my training. But I often met people on the walls or nearby who were willing to partner with me. Made some good friends that way!

In your forthcoming memoir The Sharp End of Life, you write about how you discovered sports like climbing and marathoning late in life. What was the impetus for pursuing these activities?

My kids! And my life. Stasia was my running child, and at the time I started marathoning I was juggling multiple overwhelming jobs—being Executor for my ex-husband’s very messy estate, remodeling several houses on both coasts, dealing with grief on many fronts (having just lost my father, my father-in-law, my ex-husband, and almost my son), keeping my kids on an even keel, moving offices, working more than full-time . . . I started taking our big dog out for a mindless run every night. Alex and Stasia both encouraged me to the point where I signed up for my first road race, Sacramento’s Run to Feed the Hungry.

And I wanted to understand my son’s new life—he was always “going climbing,” but I didn’t really know what that meant. So I asked him to show me how to climb. I expected to do one half-climb in the gym, learn the lingo and the gear, and see how it all worked. Then I’d go home happy with some understanding of what he does. But once we got started I relived the joy of climbing on things when I was little. I did 12 climbs that first day and was hooked!

You’ve found your own group of climbing friends. Do you think there is more interest and opportunity for older adults to become active in the sport?

Absolutely. Climbing has gone mainstream. When I started, just 10 years ago, not many people (including me!) really knew what rock climbing was about. Now, thanks to Alex, Tommy, and others, climbing is visible, people know it, and it’s far easier to find a way to begin—no matter how old you are.

How has your involvement in climbing changed your outlook or approach to life?

It’s helped me realize that I can do anything! We all can. We just have to decide to do it, and not listen to the naysayers.

It’s also changed the way I handle fear. I’ve never been a fearful person, but climbing brings out fears I didn’t know I had. And I’ve learned to deal with them. As Alex has said in many interviews, you don’t really step outside your fear, you just expand your comfort zone until what you’re doing no longer seems scary. That’s what I’ve been doing. And of course, that carries over into all parts of life. There’s a lot of scary stuff in life. Learning to deal with it more effectively is a terrific, very beneficial skill to have.

You’re asked frequently how it feels for you as a mother to know that your son is pursuing such audacious climbs. Well, how do you cope?

At the beginning, ignorance was bliss! He never told me beforehand, which I’ve always appreciated. But now I know what he’s up to out there. I knew 10 years ago; that’s partly why I started climbing. I wanted to know what climbing entailed, what he did, what he faced when he was up there. My imagination was far worse, far wilder than reality; I wanted to see first-hand what it was like to do what he does. And that’s what made it bearable.

That’s not to say that it’s easy! I’m still Mom, I still need to rein it in. But having been up there with him, having seen him on the wall, I have a deeper understanding of what he’s capable of, and that makes it a bit easier for me to just trust his judgment.

That’s what it comes down to - you have to trust your kids to make their own decisions. If you’ve taught them well, and provided opportunities for them to learn the important skills, then it’s time to step back and trust them to use what they’ve learned to follow their passion and do what makes them happy. That’s the main job of any parent. Life is dangerous; we all know that. You just have to hope that your kids prepare adequately. And as we’ve all seen in the movie (Free Solo), Alex prepares more than adequately!

You’ve been a frequent contributor to magazines and are the author of several books. What was the writing process like for you on this very personal story about overcoming adversity and raising two exceptional kids?

As I wrote the book (which took many years), I wasn’t consciously writing about ‘overcoming adversity’, or about my exceptional kids. I was just writing about what I had lived.

Every writer needs to be honest. All writing must come from the heart. If the story is honest, it will resonate with readers. It can be very hard to write a memoir. You have to be ready to really rake up all the emotions that went into your life. That can be rough.

As far as the physical process, I wrote whenever I had the time. Some days that meant I wrote from falling out of bed until falling back into bed. Some days I never had time for it. I tried to keep to a schedule, but I was teaching, and then preparing to retire from teaching, I was writing two textbooks, and climbing and running and trying to squeeze in some piano and social life…. Now that I’m retired from teaching, I hope to keep to a more reasonable schedule.

What are your future goals for climbing or travel?

There are so many places on the planet where I’d love to go climb! The few I’ve been to - Mexico, Canada, Greece, France, the northeast US - have only whetted my appetite for more. This year, I have to let my foot heal from some major surgery I had in January. Once I’m able to climb again, I’ll start working on some more trips to try out rock in some of the places I’ve dreamed about for so long…

You write in your memoir about having very limited opportunities and encouragement as a girl growing up in Queens in the 1950s. How do you compare that life with the opportunities and experiences your daughter Stasia has had?

Wow - completely different! Opposite worlds. I was raised in post-WWII New York City, in an immigrant neighborhood. We had no options. And I was a girl, in an eastern European family; a daughter did all the chores, and lived at home until some man came along, married her, and took care of her for the rest of her life. That was life, then.

I didn’t go along with that completely. I went to college (girls didn’t need that!). I traveled (too dangerous!), and generally led my own life within (some of) their parameters.

But I had children when I was older, in my 30s, and had learned a lot from my own experience. Stasia was born while we were living and teaching in Japan, and we had decided we would raise our children to be bilingual, so I gave them both that gift. I spoke only French with them. My husband spoke English. And while we lived in Japan, the world around us spoke only Japanese.

By the time Stasia was two, she had flown across the Pacific 17 times! Both our kids traveled from birth, across the country (to see my family in the east), and up and down the west coast. I took them to France several times when they were small. They experienced a lot of the world that I never experienced until I was an adult. This changes a child, gives them a different world outlook and understanding of life’s possibilities.

It was always assumed that both kids would go to college (although Alex gave up on that after one year!), and both kids knew that whatever they decided to do with their lives, we would support their choices. In my world as a kid, girls had three choices: they became secretaries, nurses or teachers—until they got married. Stasia had the whole world to choose from.

My son has summed up the generational difference succinctly: “This (our home) is where I got my adventurous spirit and mind-set that allowed me to devote myself to climbing full-time. In our household, anything was possible!”

I’m very glad they grew up believing that.

* * * * *

The Sharp End of Life is available in bookstores everywhere on May 1. Watch for Dierdre's upcoming events, attend a presentation, and be inspired by her story!

Mountaineers Books

Mountaineers Books