My thirst to belong outdoors started early. I was just in elementary school and I was being bussed across town from one district to another. I didn’t know why at the time, but I did notice that few students looked like me. My new school was awesome. It had everything I could hope for: musical instruments, better playgrounds, rad field tips, and cool teachers. We even had periodic visits from Mr. McFeely from Mr. Roger’s Neighborhood. My old school paled in comparison.

Year after year, teachers would begin our first day back in class with the question, “Does anyone want to share their experiences over the break?” The students at my new school would eagerly wave their hands and launch into fantastic tales of outdoor adventures, stories of epic road trips to national parks like the Red Rocks or Yellowstone. Some of my friends would come back from break with weird tan lines around their eyes or skin peeling from sunburns. I wondered where they came from.

As they talked, I remember feeling an overwhelming sense of awe and wonderment. Speechless in my seat, these stories permeated my mind and transported me to faraway places that I had never heard of such as Glacier National Park. My imagination was on fire, and I wanted to know more. But what I really wanted to know was, how were these adventures attainable for them and not for others? Specifically, others like me?

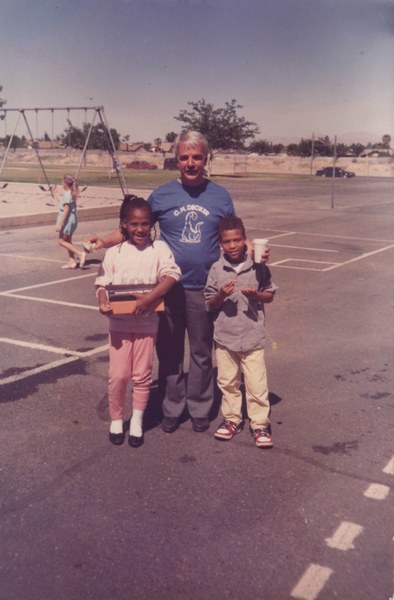

Elementary school. Photo courtesy of Annette Diggs.

Elementary school. Photo courtesy of Annette Diggs.

Looking for my place

I frequently visited local libraries, spending hours looking at outdoor magazines. I can still picture those vivid images of people climbing and skiing on mountain faces, hiking in faraway places, landing helicopters on mountain tops, paragliding above the clouds, and hanging off rock from their fingertips. It was amazing. I couldn’t get enough.

But the more I looked at these magazines and heard my classmates’ stories, the more I started to think of the outdoors as exclusive. Even as young kid, I noticed a common thread that bonded each adventurer and storyteller: their whiteness. It seemed to be a prerequisite to access these faraway places, and that idea was reinforced by virtually every form of media I encountered. No matter how hard I looked, I never found people I could authentically identify with.

I started to think I didn’t belong in the outdoors. I had no one to look up to. No one in my family did such things. Activities like hiking, skiing, and mountaineering seemed far out of reach – I knew I came from a disadvantaged background. I was a young black girl and I didn’t see any black people or very many women represented in the outdoors, much less someone who was both. I was sad and despondent as a kid because I felt like the world was saying “No” to the one thing I desired most. The lack of representation reinforced that I didn’t belong.

Fortunately, I wasn’t content with this reality. I did not accept the picture that was presented to me – I knew that I belonged outdoors, not stuck within the confines of the house wearing a dress. I remember my mom telling me that I could be anything, and I believed her. Growing up, I went on adventures with my brother where we would climb trees, wade in creeks, look for cicada shells, and hunt for lighting bugs. Through these outings I rejected what the world was telling me and found my own sense of belonging in the outdoors. I refused to let someone else define me, but as a kid I had no idea what I was up against. I did not know that in the future I would have to climb over mountains of systemic racism and overcome cultural norms to gain the opportunity to take space that was mine.

Embodying change

Eventually, these childhood dreams of adventuring were suspended, replaced with the competing priorities of adulthood. I supported myself through college, becoming the second college graduate and first scientist in my family, and established a livelihood in a new world, one of relative flatness in Memphis, TN. My weekends in Memphis frequently involved frolicking to neighborhood cookouts, eating melt-inyour-mouth barbecue, and dancing the night away at Paula and Raiford’s. In the peak of summer, you could always find me enjoying indoor amenities while seeking refuge from the suffocating heat and humidity of the South. I often reminisced about my outdoor adventures as a kid, but I rarely thought about getting out as an adult – the outdoors had become alien to me. Experiencing racism while adventuring in the South caused me to develop anxieties, and I avoided outdoor recreation as a way to protect myself from intolerance.

Change happened when I was given an opportunity to explore a new career in Seattle as a regulatory microbiologist. When I arrived six years ago, I had the false impression that all Seattle had to offer was the Space Needle and Seahawks. It was not until my second year that a coworker convinced me otherwise by taking me on a hike near Mt. Rainier. The experience completely shifted my view of the area and resurrected dreams of belonging in the outdoors. Our tick-list grew, and in short order we enjoyed the scenery around Mowich Lake, Eagle’s Nest, Spray Falls, and many other trails.

My mind was completely blown by the beauty of our trips. A cascade of joyfulness and excitement erupted from within, and I chose to follow it. I joined Seattle Outdoor Adventurers (SOA), an online meet-up group that brings people together to celebrate nature through exploration of the Pacific Northwest. I found my place of belonging with SOA, and for the first time in 30+ years I felt welcomed into the outdoors. My anxieties and fears around hiking while black were diminishing. I felt safe. I could finally let go and focus on my dreams of becoming an adventurer.

Breaking trail at Kendall Peak. Photo courtesy of Annette Diggs.

Breaking trail at Kendall Peak. Photo courtesy of Annette Diggs.

Awakening the intrepid spirit

My journey as a mountaineer started with a SOA climb of Mt. St. Helens. I prepared for the climb by taking a free self-arrest course from SOA and hiking exactly three trails: Thrope Mountain, Mt. Si, and Mailbox Peak. I did zero cardio. It was not enough training, but I was new to the game and felt enthusiastic, confident, and determined. I honestly believed that if I could make it to the top of Mt. Si and Mailbox Peak, even if only once, I was ready. If I had known the challenges in store for me, I would have trained harder.

Our team chose to do the Worm Flows route, which involves 5,699 feet of elevation gain over six miles to reach the summit at 8,364 feet. At 5am on May 9, 2015 – summit day – we had just passed beyond Chocolate Falls when the dim glow of the morning light arrived. I looked up to see the mountain reveal herself. My eyes fell upon what seemed to be a never-ending spread of exposed steep bouldering lava fields lined with coarse ash and loose pumice stones. Although it was a majestic sight to see, I was struck by the sheer enormity.

I felt both excited and terrified. We may have made it to the tree line, but so many more steps remained, rolled out in front of me as a punishing carpet of steep boulders and relentless snow fields.

As we trudged along, I could feel my brown skin burning in the sun and my lips cracking from exposure. I took a seat along a ridge to strip down to my base layers to keep from overheating. I was beat, and could feel self-doubt setting in. “What I am doing?” I thought. “What if I fail? What if I don’t have what it takes to make it through this?”

My pace slowed, gradually separating me from the majority of my team, until I was organically matched with a team member who was enduring the same struggle. We found ourselves taking break after break to catch our breath. We swapped leads back and forth, each taking a turn in front as we found our way up the mountain.

I climbed, and with each planted step and hand reach, I inched closer to the top. Stopping to adjust my gear, I looked up to realize that I had made it through the trenches of the boulder field only to be confronted by a steep, unsympathetic snow field. My confidence crumbled. I was so fatigued. I knew it was time to reach inside myself for the will to succeed. I needed to make this summit in honor of my mom, who was hiking in the environs below.

Exhausted and with an aching back, I leaned on my trekking poles and mentally negotiated the number of steps I could take in each push. The terrain went on forever, tormenting me with every seemingly insignificant foot forward. I dug deep, committing to the struggle. Focused on my own little world of step-breath, step-breath, I was surprised to look up and see faces peering down on me. They erupted into cheers, and with a few more steps I made it to the summit! I won the unmerciful mental and physical battle inside myself.

Standing on the summit, I felt the highest levels of happiness and serenity in my life. I could feel an intense connection with my body and consciousness. My mind was free of all internal and societal noise. An inner transformation had erupted and was surging through me. I stood soaking in the most beautiful landscape I have ever seen and cried at the realization that, against all odds, I was becoming the manifestation of my dreams.

Leaning in

The struggle to the summit of Mt. St. Helens was monumental for me. This achievement shattered the ceiling on how I perceived my own physical ability and mental strength. This summit unveiled what my curvy body, atypical for a mountaineer, could do with very little training. It inspired me to see what else my body could do (this time, with training), and, because imposter syndrome is pervasive, I needed to confirm to myself and prove to my team that this summit wasn’t a one-time fluke. I also wanted to pave the way for others who look like me.

Shortly after my initial summit, I joined The Mountaineers. I took a leadership course to learn more about trip planning and group dynamics. During that course I got to know other Mountaineers members, and my outdoor community expanded. I bought Freedom of the Hills and taught myself the basics. Fellow Mountaineers were incredibly supportive in helping me refine mountaineering techniques and evaluate risk. They became another part of my outdoor family, offering mentorship and inspiration for my journey. My belonging in the outdoors grew.

The following year, after investing nearly a thousand dollars in outdoor gear and equipment, my friend and I decided to tackle Mt. Adams, the second tallest peak in Washington. As we prepared for our summit over Labor Day weekend, we realized that neither one of us could afford the $400-$600 price tag for mountaineering boots. After deep trip assessment we decided to use what we had: trail runners. We waterproofed them with Ziploc bags and secured them with microspikes while going over snow fields. That’s how we reached the summit, bumping Beyoncé the entire way. That day was my friend’s first mountain summit, my second, and the beginning of a yearly Mt. Adams climbing tradition between close friends. It was truly a magical experience.

Changing the picture

After Mt. Adams I began to understand how strong I was. I became bolder, braver, and more courageous. I summited Mt. Rainier. I invested hundreds of dollars to try skiing and fell in love with it, so I worked hard to become a ski instructor at Stevens Pass, to provide representation for youth, and I discovered that representation works both ways. I have students who look at me with awe and inspiration, while some students can’t believe they have a black ski instructor. I had one student that kept saying in amazement, “You’re black, you’re black!” His blue eyes were as big as sliver dollars. I laughed and said, “Yes, I am black.” I knew he was trying to process an image he had never seen.

I grew as an adventurer and explorer by going outside my comfort zone on treks through Patagonia and the Andes Mountains. While in Chile, I missed my connection back to the states and scored extra time in Pucón. I used that time to summit Villarrica Volcano – Chile’s most active volcano. Wanting to see what else I was capable of, I went on a solo trip through Iceland’s wilderness and found it liberating. My curiosity transported me to Africa, where I summited Kilimanjaro but left brokenhearted by the porters’ working conditions. Inspired to make a change, my friends and I are now working to provide new boots for 32 porters.

The author posing with Anita Musevenzo of South Africa, the only other black woman on the mountain that day, and the second black woman Annette has met on a mountain since she started climbing.

The author posing with Anita Musevenzo of South Africa, the only other black woman on the mountain that day, and the second black woman Annette has met on a mountain since she started climbing.

Today, my passion for the outdoors runs deeper than ever. I have a tick-list and the desire to achieve things I once thought impossible. I’ve proven myself on countless trails and summited Mt. St. Helens and Mt. Adams multiple times, with Mt. St. Helens now an annual Mother’s Day tradition to honor my mom. My family and friends are astonished by what I have accomplished, and in turn they’ve been inspired to explore the outdoors, take solo trips abroad, and try new sports like skiing, snowboarding, and mountaineering. Words can’t explain how much this means to me.

I still face adversity, but I don’t let it stop me from re-defining the outdoors for myself and others like me. I use my presence as an opportunity to confront and educate others on their implicit or unconscious bias. I admit, I get frustrated when I hear the African American plight being minimized to a stereotype. But I know that the root cause is either historical amnesia, racism, supremacy, or perhaps a combination of all three. Overcoming the mindset of others is my Everest.

Not seeing a lot of minorities in the outdoors is a product of our history. My great grandmother was “the help”, her mom a sharecropper, and her grandmother was born a slave. This family history is filled with traumatic experiences in an oppressive outdoors. It’s an ugly reality and it humbles me. I want to reclaim the greater outdoors on my own terms and heal people of the past and present while encouraging others like me to do the same.

True adventure is discovering who you are. I feel that knowing what I have achieved with my body gives me the ability to see a person’s potential before they can, and I have grown obsessed with unlocking the intrepid spirit in others. I am not the most athletic person, and I think that seeing someone like me being active outdoors lets others know they don’t have to fit a mold or archetype to achieve a goal. I take joy in giving advice about gear and trip planning as it helps me realize and appreciate how much I’ve learned and how far I’ve come.

I will keep pushing for change and awareness in outdoor recreation. I understand the importance of safe spaces and have created my own outdoors where marginalized people can thrive and not have their uniqueness or any mistakes be attributed to their skin color, age, gender, beliefs, or sexuality. This space is nothing short of extraordinary, and I’m grateful I can be an example to others.

As I continue to walk through challenging spaces, as the only black woman, I am proud. Standing behind me is the strength of my ancestors and the support of my community.

I belong.

This article originally appeared in our Fall 2019 issue of Mountaineer Magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, click here.

Add a comment

Log in to add comments.Wonderful and inspiring, thanks!

Thank you for sharing Annette! Inspiring!

Annette Diggs

Annette Diggs