Other than for the sailors among us, strong winds are generally annoying. Camping, paddling, skiing, cycling – all better enjoyed without 30+ mile-an-hour gusts. We can layer up for cold and down for the heat. We’ve got Gortex to defeat the rain and snow. But wind often feels relentless in spite of our best efforts to cope with it.

In his Mountain Weather Pocket Guide, Jeff Renner provides several tips for understanding and dealing with wind when on an outdoor adventure.

“Wind is simply air moving from regions of high pressure to regions of lower pressure,” Jeff writes. “The greater the difference in pressure, the faster the air tends to move. Wind behaves very differently at varying altitudes, especially in the rugged terrain of mountains. Moving weather systems, the interaction of wind with ridges, peaks, and valleys, and the daily cycles caused by changes in solar heating or cloud cover can result in or influence changes in mountain winds.”

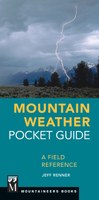

Chinook winds, for example, are common in the Mountain West. A Chinook is warm, moist air that blows in from the West and cools as it climbs into the mountains, eventually dumping its moisture. When the Chinook (same as a Santa Ana in Calfornia), crests the mountains, it picks up speed on the Eastern descent, as it warms up again. These warm winds can create a danger in both their strength and warmth, melting snow very quickly. Chinooks are prevalent in the Pacific Northwest and in the Rocky Mountains, and more prevalent in the northern states compared to southern US states.

Chinook winds, for example, are common in the Mountain West. A Chinook is warm, moist air that blows in from the West and cools as it climbs into the mountains, eventually dumping its moisture. When the Chinook (same as a Santa Ana in Calfornia), crests the mountains, it picks up speed on the Eastern descent, as it warms up again. These warm winds can create a danger in both their strength and warmth, melting snow very quickly. Chinooks are prevalent in the Pacific Northwest and in the Rocky Mountains, and more prevalent in the northern states compared to southern US states.

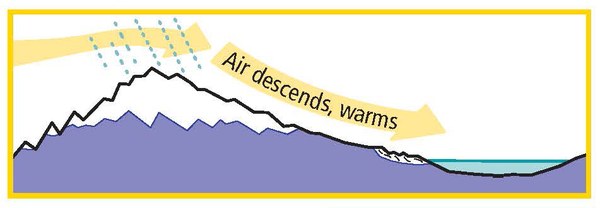

Gravity winds are another type of wind encountered in the mountains. Like its name, gravity wind will flow down steep slopes on a clear night, picking up speed especially if there isn’t much vegetation to impede it.

Gravity winds are another type of wind encountered in the mountains. Like its name, gravity wind will flow down steep slopes on a clear night, picking up speed especially if there isn’t much vegetation to impede it.

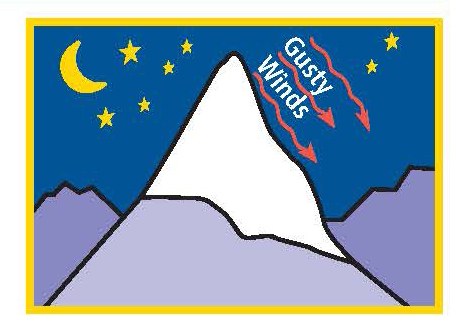

Renner’s Pocket Guide also describes gap winds. Essentially, wind flowing through a gap or pass in the mountains can double in intensity compared to the upwind, pre-gap velocity.

Renner’s Pocket Guide also describes gap winds. Essentially, wind flowing through a gap or pass in the mountains can double in intensity compared to the upwind, pre-gap velocity.

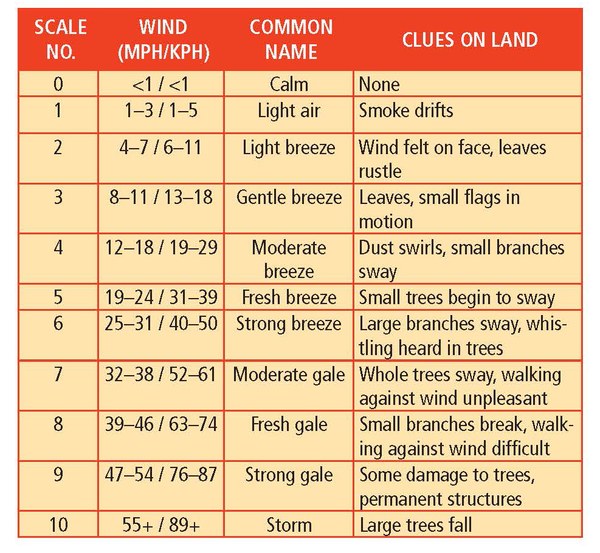

The table here (called the Beaufort Wind Scale) gives you an a sense of the seriousness of the wind by linking its speed to things you can observe when you’re outdoors.

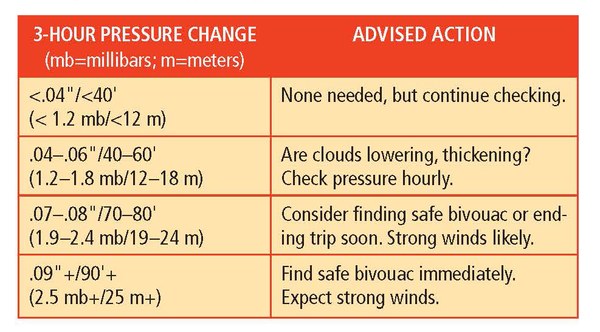

Another way to forecast wind is with your altimeter. “Use your altimeter as a barometer,” writes Jeff, “to get an early warning of high winds. Dropping air pressure will register on an altimeter as a rise in altitude, even if you are in camp, walking on a level trail, or descending.”

Dealing With Wind

Jeff offers these tips for setting up camp in a high impending wind:

- Surrounding trees of uniform size are less likely to fall in a windstorm than a stand of trees that includes isolated tall trees.

- Avoid camping near dead or unhealthy trees—they’re more likely to fall or drop branches in strong winds.

- Hanging branches may fall in a windstorm.

- Avoid camping downwind of a gap, pass, or canyon—winds will accelerate through such features.

- A hill, bluff, or large boulder just upwind will provide protection from the wind.

Once you have selected a campsite, erect your tent facing into the wind. Use solid, undamaged tent stakes and guylines. Without guylines, even a moderately strong wind can snap tent poles. The best anchoring comes from attaching guylines one-third of the way or halfway up the tent.

For more tips, pick up a copy of Mountain Weather Pocket Guide. This handy, foldout, laminate pack guide also includes illustrations and information on fog, wildfires, flash flooding, avalanche guidelines, and an explanation for understanding various cloud formations.

Mountaineers Books

Mountaineers Books