by Peter Dunau, Mountaineers Communications Specialist

As Tom Hornbein stood in the shadow of Everest, he knew getting to the top wasn’t enough. He wanted more.

In 1963, Tom was a member of a sponsored expedition designed to send the first Americans to the summit of the highest peak in the world. The strategy was clear: climb the South Col route first established by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay in 1953. While summiting via the South Col was far from a guarantee, the proven route was their best chance.

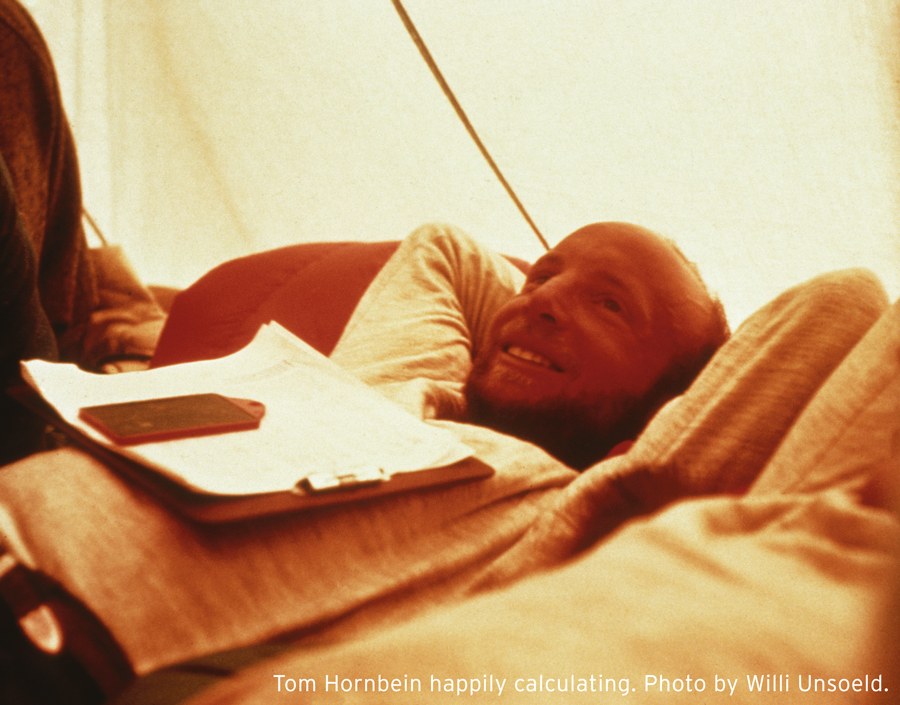

Tom understood the important symbolism and immense challenge of getting an American to the top. Prior to their expedition, only six people had summited Everest, while 16 had lost their lives on the mountain. Still, Tom and a few others made the case for an additional objective – an audacious new route up the West Ridge. The decision wasn’t made lightly. But after a reconnaissance trip, days of deliberation, and countless hours of strategizing, a subset of the expedition dubbed the “West Ridgers” got the blessing of the party. Tom and his climbing partner, Willi Unsoeld, would go for the summit via the West Ridge with a small team of expedition members and Sherpas helping until the final push.

Ultimately both routes were a success. Jim Whittaker summited via the South Col with Nawang Gombu to become the first American to climb Everest. Three weeks later, Tom and Willi summited via the West Ridge, becoming the first people to pioneer the daring, new route. But the trailblazing climbs came at a high price. Early into the expedition, Jake Breitenbach perished when an ice wall collapsed. A ferocious windstorm nearly wiped out the West Ridgers. And an emergency bivouac at 28,000 feet cost Willi nine of his toes.

Tom and Willi’s summit remains one of mountaineering’s greatest achievements. In 1965, Tom released a personal account of the journey called Everest: The West Ridge. The most recent edition, published by Mountaineers Books in 2013, celebrates the 50th anniversary of the climb and includes a foreword by Jon Krakauer. At the time of its publication, only fourteen people had succeeded on the West Ridge.

After Everest, Tom turned his focus to medicine, going on to chair the University of Washington’s Department of Anesthesiology. As a researcher, he published over a hundred journal articles and book chapters. His career carried him away from the limelight of climbing, but ever the mountain man, he continued to explore the Cascades near his home in Seattle, while enjoying the occasional trip abroad.

Tom took some time to talk with me and reflect on life and mountains. Looking back on his 87 years, he credits ridges, peaks, and couloirs as the backdrop of his enduring friendships. It’s these bonds, he says, that have given “a lot of richness to the whole damn journey.”

On the democratic nature of the American expedition:

“Right now, I’m writing an obituary for Norman Dyhrenfurth, who led the expedition. I’ve been reflecting a lot on his style of leadership. Norman said to us, “I’m not a dictator.” Indeed, he was not. In contrast to Colonel John Hunt, who led a more military-style British expedition a decade prior, our decisions were consensual. It was a lot group discussion and evening talks on the way in. We behaved as two teams – one for the South Col and one for the West Ridge – but each of us was also committed to the expedition as a whole. When you read all the mountain literature, the difference between success and failure often comes down to people getting along with each other. I think Norman did an astounding job of picking a team.”

On his climbing partner Willi Unsoeld:

“Willi and I complimented each other handsomely. As we made the case for the West Ridge to the other men on the expedition, I took on the role of being very outspoken, even a bit extreme at times. He felt exactly the same way as me, but he was able to come across as the guiding force that helped everyone reach common ground. Willi was really an outgoing, dynamic, entertaining guy. He went on to be a pioneer in experimental education, beginning with Outward Bound and later as one the founding faculty members at Evergreen State College. I remember one his favorite lines: he was talking to a mother who was nervous about signing her child up for Outward Bound, and he said, ‘Well, mam, I can tell you that if you’re trying to protect your son from risks that’s very understandable, and you may save his life, but you’ll lose his soul.’ Now that Willi’s passed away, I still call his widow Jolene every year on the anniversary of our climb.”

On fellow expedition member Barry Corbet:

“He was probably the most inspiring of all. A few years after Everest, he became a paraplegic in a helicopter accident. We got to be very good friends, much more so than on the expedition. After his injury, he became the editor of New Mobility and did so much for the spinal injury community. In writing his obituary, I reflected that if he hadn’t been paralyzed, there’s no way he could’ve touched so many lives. He was a real hero to me. He didn’t cherish me calling him that. But I eventually figured out, you can’t decide who other people’s heroes are, and they can’t decide who your heroes are. Heroes are in the eye of the beholder. Barry was numero uno hero for me.“

On the motivation behind attempting the West Ridge:

“For me, and for the little group that gravitated to the West Ridge – Willi, Dick Emerson, Barry Corbet, and Jake Breitenbach, before he died in the ice fall – it was the opportunity to go on an adventure where the outcome was unknown, where nobody had ever been before. You didn’t know what lay ahead of you and if you could really pull it off.”

On what made his West Ridge climb a success:

“Frankly, as I look back on our climb from my current vantage there was a phenomenal amount of luck. That’s reflected in all the attempts on the West Ridge since we did it. There’s been about 60 attempts and out of that only about five have been successful. Even though we had a windstorm that creamed us, so many breaks were on our side. The confluence of events that aligned for us hasn’t happened in the fifty years since.”

On whether the West Ridge was too risky in hindsight:

“No, I don’t look at it that way. I remember after we got back to Seattle, Willi gave a talk about the trip. The audience mostly greeted us with adulation, but there were a few smart people who – even though we were back alive and well – thought we were really stupid and had no business trying to do the West Ridge. That’s not uncommon in any endeavor where you venture into the unknown. You’re taking risks and you don’t know how it’s going to turn out – that’s a great metaphor for everything in life.”

On the personal drive that led him up the West Ridge and onto an accomplished career in medicine:

“For better or worse, that’s who I am! My mom and my sister used to call me, ‘Tom Mule.’ I can look back on my life and career and see times where my stubborn persistence paid off, and I can see times where if I’d been a little less stubborn I would’ve bailed a sooner, realizing I wasn’t going to get where I wanted to go. Like most attributes, it’s a two-sided coin.”

On life after Everest:

“Jim Whittaker had the pleasure – thank goodness – of being the first American to summit Everest, which he carried magnificently. For me, all I wanted to do was forget about Everest and start my career in medicine. That being said, I continued to climb in the Cascades and Cashmere crags with Dick Emerson, who was on the Everest expedition and moved to Seattle shortly after. Those were wonderful years. I also did several climbs abroad, including one in Karakoram and another in Tibetan China. To this day, I continue struggle up things albeit very slowly. I don’t have the body I did even two years ago. But I continue to wander off trail and try to avoid killing myself. I still just love the glory of the outdoors.”

On writing and publishing Everest: The West Ridge:

“It was one the more formative experiences of my life. I didn’t want to write a heroic account. I wanted to write about how people coexist and function and work together and compromise with Everest as the stage. I wanted it to be fairly unassuming and real. Dave Brower of the Sierra Club was the editor of the first edition. Dave was a legendary force in the conservation movement. Working with him was an incredible experience with a great man."

On donating the proceeds of Everest: The West Ridge to Mountaineers Books:

“To me, what Helen Cherullo (the publisher at Mountaineers Books) and her gang are doing is phenomenal. Their Braided River series on environmental issues is fantastic. With the blessing of the photographers who contributed to the book, I was happy to give the proceeds to a worthy cause.”

On what advice he’d give climbers today:

“I don’t have any advice. All I can extrapolate from my own experiences is that you fall in love with something and you follow your dreams. What you discover in the mountains is life changing. When my parents sent me to summer camp, I fell in love with the natural environment. But the enduring foundation is not the mountains; it’s the people I’ve shared them with. Over the long haul it’s enduring friendships. With Everest, for me, the best part was these relationships as they unfolded in the years after the expedition.”

The Mountaineers is honored to present Tom with our Lifetime Achievement Award at our annual gala on April 14.

Peter Dunau

Peter Dunau