The Mountaineers is partnering with the Sacred Lands Conservancy, an Indigenous-led nonprofit with strong ties to the Lummi Nation, to produce a series of educational pieces on the importance of mindful recreation and how we can all develop deeper connections to the histories of our natural places. Tah-Mahs Ellie Kinley is a Lhaq’temish fisherwoman, an enrolled Lummi Nation tribal member, an elected member of Lummi Nation’s Fisheries and Natural Resource Commission, and President of the Sacred Lands Conservancy (SLC). We hope you enjoy this blog from her, written in collaboration with SLC’s Julie Trimingham, which shares more about tribal treaties of the Pacific Northwest - which allow us to live, work, and recreate on these lands and waters - and how we can all strive to uphold them today. - Conor Marshall, Advocacy & Engagement Manager

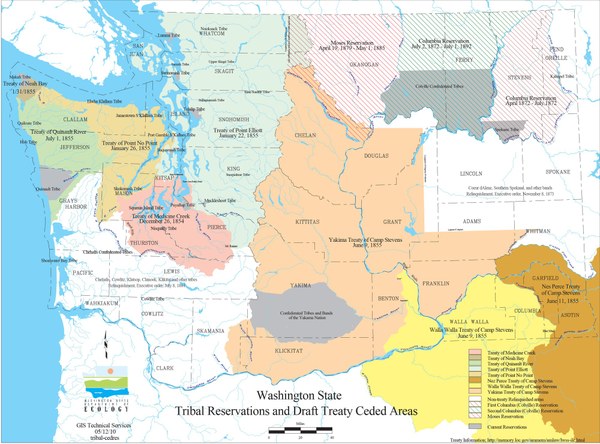

Much of what we now call the Pacific Northwest is subject to treaties negotiated between the United States and Native tribes in the 1850s. The treaties of Point Elliott, Medicine Creek, and Point No Point granted the United States rights to settle designated lands in and around the Salish Sea. Similar treaties deal with lands on the Olympic Peninsula and east of the Cascades. Washington Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens negotiated eight land treaties that pertained to Washington Territory, one land treaty co-negotiated with Oregon Territory, and one that dealt with railroad passage in what is now Montana. Collectively, these are known as the Stevens Treaties.

The land settlement treaties - which allow non-Natives to live, work, and play here - all enshrine similar principles. These treaties established reservations and guaranteed protection of signatory tribes’ rights to fish, hunt, and conduct traditional activities on our ancestral homelands - which far exceed the bounds of present-day reservations. While not all Native tribes are recognized by the federal government, and not all Northwest tribes were signatories to the Stevens Treaties, most Native people living in this region today are members of signatory tribes.

Basic information and a brief history of tribal treaties can be found in We Are All Treaty People: Part I. In this blog we share how the Stevens Treaties are interpreted, how they affect our lives today, and how we can all work to uphold our collective treaty obligations.

Interpreting the Treaties

It’s important to remember that the treaties do not grant rights to Native Americans, rather, the Native peoples granted permission to newcomers to settle on traditional Native territories. “Treaty rights” are those inherent and reserved rights that tribes have always had, and that members of the tribe can exercise. The right to fish in usual and accustomed territory is one such example.

Although the treaties negotiated by Governor Stevens promised much to the signatory tribes, many of those promises have been broken or left unfulfilled. But a treaty broken is not a treaty annulled. The treaties are still in effect, and it is our collective responsibility to uphold them, ensuring all the rights are vigorously protected.

A few foundational principles for interpreting the treaties include the idea that treaties are, according to the Constitution, “the supreme law of the land”; that they are forever binding; and that treaties should be understood in the way that the signers of the treaties understood them.

At the time of treaty signing, we were told, and it is passed from generation to generation, that “as long as the mountain still stands and the rivers still run” that our rights to harvest our traditional foods and medicines in our usual and accustomed territories would be protected by the treaties. Thus, we understand the treaties to be in effect in perpetuity.

At the time of treaty signings, the rivers ran free and clean, the lands were rich with life, and the Salish Sea and all her waters were thick with salmon. Our ancestors signed the treaties to protect our access to that bounty. We must interpret the treaties with a view to the natural world as it was then. We understand the treaties to guarantee the abundance that is required for us to exercise our treaty-protected rights.

The Fish Wars

Salmon is often at the heart of discussions about treaty rights, as it is a sacred protein throughout this region. We are salmon peoples. Salmon connect the inland rivers and lakes to the sea and open ocean. Our ancestors knew that the health of salmon was connected to ecosystem health and the survival of many area Native peoples. As rivers have become dammed, waterways have become industrialized, and land-based pollutants have leached into the water, fish populations have precipitously declined.

In the 1960s and 70s, Washington State tried to manage some of this decline by restricting tribal fishing. The result was that some tribal fishermen were arrested for fishing off their reservations, but still within their traditional territory. Fishermen and other tribal members protested, using civil disobedience tactics similar to those being used in the Civil Rights movement. “Fish-ins” often ended in arrests and non-tribal violence against tribal members.

The Federal government, whose responsibility it is to uphold the Treaties, finally intervened in the “Fish Wars” and sued the State of Washington. The resulting Boldt Decision in 1974 clarified and affirmed treaty rights for tribal fishermen. Judge Boldt ruled that tribes had the right to half of the harvestable catch in their traditional waters. At this time, the tribes became co-managers of the fisheries, along with the State of Washington.

While the 1980s saw some good fishing years, salmon and other fish runs have continued to decline, especially with the accumulated effects of various pollutions and the accelerating effects of climate change. Tribal members whose livelihoods used to depend on fish have had to supplement their incomes or find other work altogether. As Billy Frank, Jr, the late activist and veteran of the fish wars said, ”If there's no fish, there's no fishing.” We were promised half, but half of nothing is nothing.

In 2007, federal courts ruled that Washington State is obligated to ensure that fisheries are robust enough to provide a “a moderate living” for fishermen who belong to treaty tribes. The ruling mandated that Washington State remove or repair any culverts impeding salmon passage. In 2018, the “Culverts Case” ruling was upheld by the Supreme Court. This ruling could potentially affect entities that own or manage structures - like culverts, floodgates, dams - that block or otherwise harm salmon runs. We cannot mitigate all the effects of climate change and decades of pollution on our fish runs, but we must take achievable steps to protect our Treaty-protected rights.

Treaties Protect our Shared Home

Treaty rights, while they can only be exercised by signatory tribes and their members, actually benefit all of us. By protecting fishing, hunting, and harvesting rights, they serve to protect the health and vitality of our shared lands and waters.

In 2011, Gateway Pacific Terminals (GPT) announced its intention to build what would have been North America’s largest coal export facility at Xwe’chi’eXen (Cherry Point), just outside of Bellingham, Washington. Cherry Point has long been coveted as a port because its natural deep water trench requires no dredging to accommodate massive ships and tankers. Those deep waters also provide an ideal home for phyto and zooplanktons, making for an especially rich ecosystem that was once home to Washington’s largest stock of herring. When the GPT plan became public, many local residents - along with climate change, environmental, and public health activists - protested, but a new coal port seemed inevitable.

When the Lummi Nation invoked treaty rights - demonstrating that the terminal facility and related shipping activity would negatively impact our ability to harvest fish in our usual and accustomed territory - the project was completely stopped. When Native sovereignty is understood, when treaties are honored and upheld - when promises are kept - we collectively safeguard the land, waters, life, and ancestral wisdom of our shared home.

How to Uphold Treaties Today

Know which treaty pertains to you

The Native-lands.ca map is an excellent resource that you can search by treaty, Indigenous territory, or language. If you live in the Salish Sea (Puget Sound) area, you’re subject to the treaties of Point Elliott, Medicine Creek, or Point No Point. Much of the Olympic Peninsula is covered by the treaties of Makah and of Quinault. All of the Stevens Treaties are listed, and linked to, below.

Share your knowledge of the treaties with others

As citizens of the United States, we are all bound to uphold the treaties, but so many of us on treaty land really have not had the chance to learn about what the treaties are. Collective learning is about growing together in a good way.

Support Native nations and tribes

It’s important to follow the lead - rather than get ahead - of the treaty nations and tribes. Only a treaty tribe will truly know how their inherent and/or reserved rights are being infringed upon and need bolstering. Only they will know how their rights to fish, hunt, and harvest in usual and accustomed areas are being affected. Only they will know when to bring the issue of treaty rights to the table. But when they do bring up treaty rights, please support them! Again, all of us are responsible for ensuring that the United States government keeps its treaty obligations.

Right now, Yakama Nation, Nez Perce, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, and the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation are calling for the lower four Snake River dams to be breached so that salmon populations might be restored. These treaty tribes collaborated on the Columbia Basin Restoration Initiative, which the Biden Administration has now funded. The federal government has not yet decided to breach the dams, but is committed to replacing services currently provided by the dams, and to working toward next steps.

Read the treaty that pertains to the land on which you stand

The treaties discussed broadly in this post are those which Governor Stevens drafted and executed for land then known as Washington Territory. One of the Stevens treaties (Blackfoot) pertained to building a railroad; the others, listed here, call out “the right of taking fish at all usual and accustomed places.”

Washington state Tribal reservations and draft treaty ceded Areas map from the Washington Department of ecology. View a larger version of the map here.

Washington Territory Land Settlement Treaties

- Treaty of Medicine Creek (1854): Nisqually, Puyallup, Squaxin Island, Muckleshoot, and others. Established the Puyallup, Nisqually, and Squaxin Island reservations in the southern part of the Salish Sea (Puget Sound).

- Treaty of Point Elliott (1855) included signatories from Duwamish, Suquamish, Snoqualmie, Snohomish, Lummi, Nooksack, Sauk Suiattle, Upper Skagit, Swinomish, as well as other tribes of the greater Puget Sound region. Established the Suquamish Port Madison, Tulalip, Swinomish, and Lummi reservations, which are located roughly from the Seattle region north toward the Canadian border.

- Point No Point Treaty (1855): Twana/Skokomish, Jamestown S’Klallam, Port Gamble S’Klallam, Lower Elwha. Established Skokomish Reservation, close to Hood’s Canal.

- Quinault Treaty (also known as Treaty of Olympia; 1855-56): Quinault, Quileute, Hoh. Established the Quinault Indian Reservation on the Olympic Peninsula.

- Treaty of Neah Bay (1855): Makah. Established the Makah reservation located at the northwestern tip of the Olympic Peninsula.

- Treaty of Walla Walla (1855): Walla Walla, Cayuse, Umatilla. Negotiated with the Governor of Oregon Territory. Established Umatilla Indian Reservation in northwestern Oregon.

- Treaty with the Yakama (1855): Yakama confederated tribes and bands. Established Yakama Nation in south-central Washington.

- Treaty with the Nez Perce (1855): Nez Perce. Established Nez Perce reservation, located in Idaho and parts of Washington and Oregon.

- Treaty of Hellgate (1855): Bitterroot Salish, Upper Pend d’Oreille, Lower Kutenai tribes. Established Flathead Indian Reservation in what is now western Montana.

Read more content from Sacred Lands Conservancy in this first post on tribal treaties our other pieces shared on our Honoring Native Lands and Peoples page.

Sacred Lands Conservancy with Tah-Mahs Ellie Kinley

Sacred Lands Conservancy with Tah-Mahs Ellie Kinley