It was the hike that almost never was. Out of the woods, with ash-encrusted nasal passages, I wished it was the hike that wasn’t. My friends and I had planned a four-day, 48-mile backpacking loop along the remote eastern boundary of Yosemite National Park. Fires flamed all over the west from a surge of hot, dry, windy weather, but where we headed the skies were clear. A reconnaissance hike the day before revealed a moderate air quality index. There was some haze, but no taste or smell of ash. We decided to go for it.

Following a long day of hiking and a starry evening at our lakeside campsite, the wind shifted direction. Soon, we were seeing and breathing smoke. Large ash flakes rained down on our tents. Without up-to-date information, we didn’t realize how close the fires had moved.

We studied our paper map for escape routes beneath ash-covered skies. The nearest trailhead was over a day away. Without a workable alternative, we stuck to our original plan and continued our trek toward the trailhead where our car waited. We gritted our teeth (literally), and toiled along the trail, using bandanas and neck gaiters for masks. What had been planned as a flowery, midsummer lark became an unhealthy slog through an otherworldly sepia landscape.

The Sourdough Fire above Lake Diablo, 2023.

The Sourdough Fire above Lake Diablo, 2023.

Hiking above Ross Lake, where the Sourdough Fire would soon burn in the distance.

Hiking above Ross Lake, where the Sourdough Fire would soon burn in the distance.

Wildfire risks are increasing

Wildfires have always been present in western U.S. forests and provide numerous ecological benefits. Though, in recent decades, fires have become more frequent and severe. Wildfire season now starts sooner and ends later, as a changing climate has created susceptible ecosystems. There is less water storage in mountain glaciers, the mountains are “drier” during the hottest months, and as fire season has grown, so too has what land managers call the “wildland-urban interface,” meaning homes have been built where trees once grew, putting more infrastructure at risk when a fire occurs.

There is never a year without fire or smoke. Moreover, fires are occurring more frequently on the west side of the Cascades where they were once rare, such as the Norse Peak Fire that incinerated trees on the popular peak near Crystal Mountain ski area in 2017. That same year, the Jolly Fire burned hiking areas in the Wenatchee National Forest, and in 2022, the Bolt Creek Fire scorched hiking trails around Skykomish. In 2023, I enjoyed an idyllic climb under cerulean skies of Desolation Peak above Lake Ross. Two weeks later, the area closed when the Sourdough Fire burned the slopes near Lake Diablo.

Wildfire is a fact of life that coincides with prime hiking season. Just as we plan around avalanche risk in winter, we need to plan around fire’s inevitable occurrence in order to continue hiking, backpacking, and climbing safely.

Mountaineers on Merchant Peak, looking at Baring Mountain as the Bolt Creek Fire broke out, 2022. Photo by Alison Dempsey-Hall.

Mountaineers on Merchant Peak, looking at Baring Mountain as the Bolt Creek Fire broke out, 2022. Photo by Alison Dempsey-Hall.

Planning your trip

While we cannot predict nor control wildfires, we can plan for and around them. I like to think of the following as the Four Wildfire Essentials:

Plan with wildfire in mind. Part of planning with wildfire in mind means knowing how to minimize your impact on wildfire risk as a recreationist. Be aware of any fire restrictions in place, ensure campfires are completely out before leaving, learn how to safely operate your outdoor equipment, and practice Low Impact Recreation principles.

Be mindful of where wildfires have occurred, are occurring, and are likely to occur. Helpful planning tools include trip reports and maps from the National Interagency Fire Center (nifc.gov/fire-information). Forest fire information is updated daily on their InciWeb incident data system, including detailed maps. For those who use Gaia Mapping, the pro-version includes a “Current Wildfires” data layer, which is derived from National Interagency Fire Center information. CalTopo has a similar fire history map layer.

Another helpful resource is the Environmental Protection Administration’s AirNow website (airnow.gov, also an app), which provides current information and forecasts on air quality. The website has a link to current fire information from the Inciweb system.

Remember, these planning tools are available online; they won’t help you once you are in the mountains and off the grid. Always remember to carry a paper map.

Note your escape routes. Make note of nearby trailheads along your intended route so if conditions change, you can bail or seek help as needed. Another useful practice is to plan a back-up hiking itinerary in the event your preferred route is disrupted. Our smoky hike in the Sierras was in fact our back-up plan — we moved our hike south to avoid northern fires. Not every plan works out, so it’s crucial to have a backup plan and escape routes.

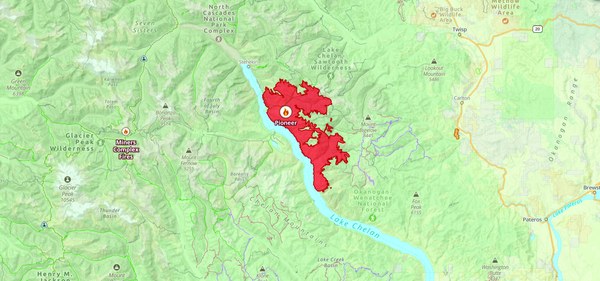

Gaia's "Current Wildfire" data layer depicting a fire at Lake Chelan, 2024.

Gaia's "Current Wildfire" data layer depicting a fire at Lake Chelan, 2024.

Leave a detailed itinerary with a trusted friend or partner. Your friend or partner can let authorities know you are in the backcountry as conditions warrant. Consider checking in with the Wilderness Information Center or National Forest Ranger District office a day or two before your hike to make sure you’re up-to-date on local conditions and so land managers know your plans.

Prepare for hiking in smoke. As an 11th Essential, add an N-95 mask to your first aid kit. This mask weighs nearly nothing and will protect your lungs should you need to exert yourself in smoky conditions. If you don’t have an N-95, neck gaiters and bandannas can be used as masks.

Even light smoke is an irritant, so consider increasing your water intake and carrying eye drops. These simple measures will ease common symptoms from smoke, such as itchy throat and eyes. Don’t forget electrolyte replacements, which are especially useful in hot, humid conditions. If you have a satellite communication system like InReach, the friend with whom you leave your itinerary can send you daily text updates on nearby wildfires and forecasted conditions.

Crossing burn areas and when the worst happens

Hazardous conditions exist not only during wildfires, but after. For several years following a wildfire, burned trees will fall or shed limbs and burned roots and overturned trees will loosen mountain soils, leading to unanticipated soil movements and elevated risk of rockfall. Risk is highest in burned forests on windy days and when traversing steep, off-trail burned slopes. I once counted over 90 newly-downed trees within a five-mile walk in the Methow Valley five years after a destructive forest fire and months after summer crews had logged out and reopened the trail. Strong winds had uprooted the additional dead timber. While nature may regenerate quickly, the cautious hiker will anticipate the elevated risk encountered on burned slopes, especially on a windy day.

What should you do if the worst happens and you find yourself in imminent danger from a forest fire? Stay calm. Alert authorities if you have InReach or a cell signal. Consider whether you are upwind or downwind from the fire — you want to escape upwind and away from the fire. Try to keep a ridge, a pond, or other terrain features between you and the fire. Check your map for an escape route, a nearby lake, or a nearby safe zone like a large, open rocky area. If a fire is approaching faster than the pace you can move, look for an inflammable terrain feature like a large rock or rock overhang. Lie next to it face down so you are breathing as close as possible to the ground.

Backpackers on their way to Napeequa valley. Photo by Cheryl Talbert.

Backpackers on their way to Napeequa valley. Photo by Cheryl Talbert.

When the world goes up in flames around you

As I flew home from my smoky backpack in the Sierras, traveling at 500mph up the eastern flank of the Cascades, I saw my wilderness world on fire. Watching the smoke, I reflected on our recent trip and the precautions we had taken. Even though we shifted our route and checked air quality and fire websites before leaving, we still encountered fire risk. When smoke reached us, we had to continue onward. We masked up and tried to stay healthy. When the world goes up in flames around you, you do your best. Your best should hopefully be good enough if you have planned well.

Take Action for Wildfire Response and Resiliency

As we grapple with the many challenges presented by more frequent and intense wildfires, it can be hard to know how to help. The Mountaineers is striving toward a more wildfire-resilient future by engaging in joint advocacy with our partners at Outdoor Alliance to build support for funding and legislation that support wildfire response and resiliency. Join our advocacy by sending a message to your members of Congress urging their support of several bills that invest in solutions to the wildfire crisis.

This article originally appeared in our fall 2024 issue of Mountaineer magazine. To view the original article in magazine form and read more stories from our publication, visit our magazine archive.

Charles Bookman

Charles Bookman